Chapter 34. The War Reaches Le Touquet

In May of 1940, the war with Germany was about eight months old and not yet very real to the people of Le Touquet-Paris-Plage. Hitler had finally gone too far, people said. How long can he possibly last against the combined might of the French and British? There was much gloating about the Maginot Line (the French fortifications along the German border) and its impenetrability, in contrast to the German Siegfried Line, which was characterized as little more than a barricade.

The beautiful beaches of Le Touquet, which Lisa and I visited almost daily, began to fill with British soldiers who had been brought across the English Channel at nearby Dunkerque to help the French whip the Germans. They were confident, young, handsome, and full of fun. They sang “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” and “We Will Hang Our Laundry on the Siegfried Line” as they wandered around town flirting with the girls. The titles of those songs were the first words of English I learned. I loved those British soldiers. To me, they were living proof that the Nazis would soon be finished off, making it possible for me to rejoin my family. Every day I contemplated my postcard photo of the Pan Am Yankee Clipper that I dreamed would soon transport me to America.

But one day we heard some alarming reports on the radio that the Germans might be advancing toward Paris. Could it be that they had actually crossed the Maginot Line? Nobody could understand how such a thing could have happened. Two days later, France was in crisis. The radios blared, “Paris has fallen to the Germans! All Frenchmen must report immediately for military duty to defend their country! Au secour de la patrie!”

That same day, Monique, Ginette, their mother, and I stood outside our houses watching hundreds of men assemble in a nearby square for conscription into the armed forces. Monique and Ginette were crying because their father, a policeman, was among them. Even our school principal had to enlist. Madame Cousin said that she was grateful that her enlisted son (Monique’s and Ginette’s brother) was safely stationed in Beirut. I tried to reassure Monique that the only reason the Germans had reached Paris was that the French had been caught off guard. The Germans, now stranded on French soil, would soon be finished off, whereupon her father would be able to return home. I felt that I could speak with authority, as I had grown up among the Germans and knew them first-hand.

Chapter 35. Air Raids

The next night I was awakened by a strange and frightening new sound — distant explosions that made the house shake and the window panes rattle. Each explosion was preceded by a whistling noise. I called Lisa, but she was out of hearing range somewhere downstairs. I became frightened and ran downstairs. Lisa was staring out the window into the blackness.

“What are those noises?” I asked her.

“It’s nothing to worry about,” she replied, but her tone and demeanor belied her words. At that moment I became aware of a sound I had not noticed before, that of airplane engines.

“Could it be that planes are dropping bombs?” I asked, fearing that I knew the answer. Lisa just kept staring through the window. A few minutes later, a man who lived across our little courtyard knocked on the door. Lisa jumped to her feet to let him in.

“It’s German bombers,” he said. “I was talking to some of the men outside. But they are bombing only the airfield.”

“Are you sure they won’t bomb our house?” I asked the man.

“Of course not,” he said reassuringly. “They aren’t interested in this house. We’re safe here.”

The air raid lasted less than an hour. After the “all clear” siren had sounded, I went back upstairs to sleep, still quite upset. I kept reminding myself that the Germans weren’t supposed to be able to hold out for long against the combined might of the French and British. And didn’t those sharp looking British soldiers, who seemed to know their business, sing “We will hang our laundry on the Siegfried Line?”

The next day, I learned that window panes had been broken in some houses, and friends showed me a fearsome looking razor-edged piece of bomb casing, the size of a man’s hand, that had been found stuck in a tree trunk.

That night, as I lay in bed, the air raid sirens sounded again. A few minutes later, again came the bomb whistles and blasts amid the droning engines of bombers. Would the panes of the window over my bed shatter? Would I get blown up? My terror peaked during the two or three seconds of ominous whistling before each blast, as I wondered how close to our house the bomb would fall. I tried to comfort myself by remembering that the man had said that the Germans were interested only in the airfield, which a safe distance away. But many of the explosions sounded a lot closer than the airfield. Lisa sat on my bed and held my head as I sobbed with terror during the twenty minutes or so that the air raid lasted.

“From now on I want to sleep in the living room downstairs,” I said to her, figuring that the more house there was between me and the planes, the safer I would be.

Drawings made in Havana in late 1941.

Upper Left: The beach in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage where we went swimming every day in the summer of 1939.

Upper right: The pine woods around Le Touquet-Paris-Plage where I took long solitary walks.

Lower half: A scary German bombing raid in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage.

Chapter 36. Adjusting to the Air Raids

As the raids became regular, I got somewhat used to them. My fear became manageable, even when bombs fell closer and window panes did break. I felt that if there were real danger, Lisa would do something. And I was still convinced that the Germans would soon be annihilated.

The kids and I practiced imitating the engine sounds of the German bombers and of the French and English planes. The German bombers had a lower pitched pulsating sound, while the French and English planes had a higher pitched, steadier sound. Once or twice I even ventured outside during raids to catch a glimpse of the bombers, in spite of Lisa’s admonition to stay inside. Children were warned not to pick up any objects on the streets because the Germans were supposed to have dropped booby traps — small bombs disguised as toys. I didn’t have to be convinced.

The whistling sounds of the bombs that once filled me with such terror were becoming less frightening. I had been told that if you can hear a bomb, it won’t hit you, and that if a bomb heads directly toward you, it is inaudible to you. I didn’t find that principle completely reassuring, however, as I thought that a bomb could still hurt me even if it didn’t hit me directly but landed, say, ten meters away from me.

Chapter 37. Fleeing from Le Touquet

After about a week of daily air raids, the French authorities told us that some people had been killed when bombs hit their homes, and that from now on we would have to spend nights in the town’s air raid shelters. The radio also said that the Germans were advancing beyond Paris, possibly toward us.

“The Germans will still lose the war, won’t they?” I asked Lisa.

“Eventually,” she answered. “But we must get away from Le Touquet just in case they do come this far.”

Though that upset me, I took some comfort in the fact that Lisa seemed to know what she was doing and was acting decisively. She had already begun to pack our essential belongings, which included my wax crayons but not, to my chagrin, my bow and arrows or my butterfly equipment. I was upset at the thought of being separated from them and from my beloved Monique. The prospect of leaving Le Touquet so suddenly was scary, but I understood that our lives were in danger and that we had to flee.

We spent that night in the basement of a large downtown hotel crowded with hundreds of people. Everyone slept on blankets and mats spread out on the concrete floor. Late that night, I was occasionally awakened when the basement floor shook from the explosions above.

Lisa roused me at five o’clock the next morning. The people around us were saying that this had been the worst air raid yet.

It was a sunny morning when we emerged from the hotel basement, but what we found was not the Le Touquet of the previous day. Some familiar buildings had been severely damaged during the night, a sight I found quite upsetting and frightening. I had never before seen violence and destruction against my own environment. What if I had been there when the bombs were falling? Clearly, the bombers wouldn’t have cared, and even Lisa couldn’t have protected me.

The streets were lined with cars, trucks, pushcarts, baby carriages, and bicycles, all being loaded with their owners’ belongings. The roofs of many cars were piled so high that the cars seemed in danger of keeling over. I had the feeling that not only buildings, but also the structure of our lives had been destroyed.

Chapter 38. We Join the Refugees

Lisa carried a suitcase and we each had a rucksack on our back.

“We must find somebody who will take us along,” she said, “but before anything else, we have to buy some food for the road.”

Most of the stores were closed, but Lisa was finally able to buy a baguette and a piece of chocolate. Then we went from car to car and truck to truck, asking the owners whether they had room for us. No one was willing to take us. Lisa’s asking soon turned to plead¬ing. We felt like beggars.

Lisa was becoming desperate. She approached the owner of a big farm truck. He said that they had no room and were returning to their home in Belgium.

“Belgium would be wonderful,” Lisa said. “We could spend a few months in Belgium and sit out the war there.” The truck was loaded with farm equipment and way on top was a tractor with seats that faced toward the rear.

“You could let us sit way up there on those two tractor seats,” Lisa suggested. “We could strap ourselves to the tractor and you’d never know the difference.”

The farmer seemed to feel sorry for us. He thought for a few moments, went to speak to some of the people who were with him, and soon came back smiling.

“If you think you can sit up there without falling off when the road gets bumpy, it’s okay with me,” he said in a gruff but friendly voice. Relieved and grateful, we climbed up on the tractor. The farmer helped us strap our baggage and ourselves securely to the tractor’s metal seats. Lisa insisted that I be tied not only to the tractor but to her as well.

Chapter 39. On the Road

The streets filled up with refugees as we waited patiently on our lofty perches for the truck to start moving. After about two hours it did. We then crept along at only about two kilometers per hour, starting and stopping, as we couldn’t go any faster than the pedestrian refugees who were jamming the road. From our high vantage point we had a panoramic view of the bedlam below. The road was overflowing with bicycles, pushcarts, baby carriages, automobiles, occasional trucks, and pedestrians carrying their children and belongings. It was a pathetic sight.

Lisa was very uncomfortable in her tractor seat, which was not nearly large enough to accommodate her, and she complained that the ropes and straps were cutting into her. I had never before heard Lisa complain about a physical discomfort. I wasn’t comfortable either, and had to hold on for dear life, or so it seemed, each time the truck started.

“How much farther to Belgium?” I kept asking Lisa.

Not having had breakfast, I soon became quite hungry. Lisa stuck a piece of the chocolate into the baguette, French style, and gave it to me.

“Don’t you want some of it too?” I asked.

“I’m not hungry,” she answered. I didn’t believe her, as she hadn’t had breakfast either, but was too famished to turn down her generosity. I also sensed that I might have to wait a long time for my next meal.

Occasionally we saw French and British bombers and fighter planes flying east, the direction in which we were headed. I silently cheered them on, hoping that they would be able to stop the Germans.

By the end of the afternoon, after about ten hours on the road, we had moved only about seventeen kilometers. Lisa was in pain and pointed out that we could have walked faster.

Suddenly, some of the traffic began to flow in the opposite direction. Refugees were coming back through the fields alongside the jammed road.

“Retournez! Retournez!” (Go back! Go back!) they shouted. “The bridges have been blown up! The Germans are coming from that direction! You are heading right into them!”

Lisa turned pale. I was scared and felt my heart racing. But our truck didn’t turn around. Instead, it turned into a side road that led into the woods. There was no traffic at all on that road, and we were suddenly going very fast. We held on to our seats tightly. Our hair was blowing in the wind. It was exhilarating.

“Franzi, I think we are saved,” said Lisa.

I was sure she was right. At this rate, I figured, we would soon be in Belgium. But our elation was short-lived. The road narrowed, became bumpy, and came to a dead end in the thick woods. The farmer and his other passengers got out.

“We’ll have to spend the night here,” he said as he helped untie us. “There was no point to staying on the highway.” He and the women who were his passengers seemed grumpy and immediately started opening wine bottles.

Chapter 40. In the Woods

We looked around. The woods were dark. It was seven o’clock in the evening but still light. Through a clearing, I saw, in the distance, a small stretch of the highway on which we had just spent the day. I could just barely make out the refugee traffic, its direction now reversed and moving back toward Le Touquet.

Lisa sat down, leaned against the base of a large tree, and wrapped us in a blanket. I was starving again.

“We still have a small piece of chocolate,” said Lisa. “Eat it slowly and reverently (she used the words mit Andacht), because you probably won’t get anything else to eat until tomorrow.” Upon finishing it, I felt some concern when I realized that I was still hungry.

It was not long before we began to hear a familiar rumbling in the distance, the sound of distant bombings.

“It’s probably the French and British stopping the Germans, right Lisa?” I asked anxiously.

“Yes, that’s probably it,” said Lisa. “And you might as well get some sleep now.” Moments later I was asleep in her lap.

At dawn, I was awakened by some new sounds — the trumpeting drone of the maneuvers of fighter planes, punctuated by anti-aircraft fire. Though only half awake, I realized that an air battle was in progress. It wasn’t exactly over us but sounded closer than the previous evening’s battle. I got up and joined Lisa and the Belgians, who were peering in the direction of the battle sounds through a clearing in the trees. We could see distant puffs of smoke floating in the sky, and planes, barely visible as small specks, executing large arcs and pirouettes as they maneuvered in evasive patterns.

Suddenly, I saw a series of small, compact, fresh puffs exploding around a fast-moving speck of a plane. A few seconds later came the pop, pop, pop sounds of the explosions. At first I thought that the puffs might be exploding planes. When I expressed my alarm to the farmer, he explained to me that the puffs were only flak, the exploding shells of the anti-aircraft fire from the ground.

Why was the battle coming closer instead of receding? Why weren’t the French and British pushing the Germans back? Lisa had no answers.

The puffs of flak were now bigger and closer, and the sounds of their explosions followed the appearance of the puffs by less than a second. The bombs, too, sounded as if they were falling closer to us. I looked toward the highway on which we had spent the previous day and saw that it was now empty. The refugees were gone.

Chapter 41. Spotting the German Tanks

A little later I looked again in the direction of the highway. This time I saw an upsetting sight — tanks and trucks moving in the direction of Le Touquet. I hoped that they were French or British, not German.

“Look!” I exclaimed to Lisa and the farmers, “Tanks and trucks!”

“Are you sure?” asked the farmer. “I can’t see that far. Tell me exactly what they look like. Are you sure they aren’t refugee trucks?”

“I’ll draw them for you,” I answered. Lisa took my pad and the hard wax crayons and a pencil out of one of our rucksacks, and I began to draw what I saw. The farmers were now crowded around me.

“My God, look how well he draws,” said one of the women. “How old is he?”

“Comme il est mignon!” (He’s so cute), said another. “Look, he’s drawing a tank.”

“Do you see any markings on the tanks?” asked the farmer.

I looked intently. It was difficult to make out any markings. The narrow gap in the trees revealed each vehicle for only a moment.

Then, for an unforgettable split second, I saw a black cross on a tank turret. A chill ran down my spine. This was the same mark I had seen on the German bombers in Le Touquet. I knew what that meant and was too upset to say anything. So I solemnly drew the heavy black plus sign on the turret.

“Did you really see that?” asked the farmer sternly.

“Yes,” I answered gravely.

My half completed drawing was grabbed away from me. Pandemonium broke out among the Belgians as they passed it around.

“Do you believe that he really saw that?” asked one of the women.

“How could he have drawn it without seeing it?” said another. They were upset and screaming at each other. They even put away their wine bottles. Lisa was expressionless.

For a moment I felt important and valuable to Lisa, but that feeling was overwhelmed by fear as I realized that neither Lisa nor the Belgians would be able to protect me from the Germans. There was no safety net anywhere.

“Will the French and British drive the Germans back?” I asked Lisa. It seemed to me that this was the only hope at this point.

“I don’t know,” she said in a discouraged voice.

I drew one more picture of the German vehicles and one of the planes, hoping that drawing would calm me down. But it didn’t work. I had forgotten my gnawing hunger and just wanted Lisa to cuddle me.

Chapter 42. The Air Battle

Suddenly, the air battle was directly above us. Planes were diving, climbing, and making arcs. The trumpeting sounds they made as they drove their engines to the limit were deafening.

Though extremely frightened, I watched the action. I was momentarily encouraged when the farmer told me that the French and British planes were dive-bombing the German tanks and trucks. I rooted desperately for the French and British planes, hoping they would shoot down the German ones, but preferably out of my sight. I realized that the planes were directing their machine gun fire only at each other, but wished they wouldn’t do that right above us. What if the bullets were to fall down and hit us? And what if a plane should actually be hit and come crashing down on us?

Soon enough, a high flying plane I happened to be watching began to trail black smoke and then flames as it plunged earthward with a loud trumpeting noise.

“Can this really be happening?” I wondered. “There must be a live pilot in that plane. In a few seconds he’ll be dead and he probably knows it. How close to me will the plane hit the ground?” I didn’t wait to find out, and hid my face in Lisa’s lap with my fingers in my ears. But I couldn’t block out the loud drone of the plunging plane or the boom of the ground-shaking explosion when it crashed. At that point, my fear turned to terror. I began to cry and kept my face hidden in Lisa’s lap.

There were many more plane crashes that afternoon. It seemed only a question of time until one of those planes, possibly even with its cargo of bombs, would fall on us. What was particularly frightening to me was that the explosions and plane crashes were occurring with total disregard for my life or safety, and that it was a matter of complete indifference to those pilots whether I lived or died. They didn’t even know I existed. And there was nothing anyone could do to protect me. I was at the mercy of chance.

“Those poor pilots,” I kept saying, so as to give Lisa the impression that my anguish was more for the pilots than for myself. I was a bit embarrassed to be filled with concern only for my personal safety when everyone around me was in the same danger, and others were actually being killed.

Chapter 43. Dealing with Fear

My recollections of the next two days are patchy. Sometimes I kept my fingers in my ears, not just to shut out the sounds but also to help pretend that the whole thing wasn’t happening. I remember a blur of explosions, plane crashes, and the continuous deafening racket of droning plane engines and machine gun fire. I remember crying, napping, getting soaked by rain, and feeling filthy. And I was starving. And yet, when one of the Belgian women offered me a potato like vegetable that had been scavenged from some local fields, I was unable to eat it, in spite of not having eaten since that last piece of chocolate two or three days before. My problem was terror, not hunger. I kept offering “deals” to fate, promising to do all kinds of wonderful things if my life were spared.

At some point during those days I devised a way to manage my terror. I decided to consider myself already dead, so that I would have nothing more to fear. I thought about it for a while, sad and outraged at being pushed to such an extreme step. I cried a little when I thought about how my parents and grandparents would mourn me. Of course I didn’t tell Lisa about this plan. Why upset her even more? I was also somewhat reluctant to reveal my secret skill in managing my emotional states, a skill I’d had many opportunities to practice since Father had left me in Paris almost two years before.

It took me a little while to convince myself fully that I was really dead, but once I did, I felt a sense of relief from fear — a calm detachment or trance-like state. The explosions seemed more remote; I felt more like an onlooker. Terror still broke through occasionally, especially when battle sounds woke me up from naps and I realized that the recent events were no mere nightmare. But then I would regain my equanimity by reminding myself that dead people had nothing to fear.

Chapter 44. When the Smoke Cleared

We spent the third night in a hay cart that the Belgian farmers had found or stolen. Lisa and I were given a choice spot in the wet straw, and Lisa covered me with something to protect me from the rain.

The next morning Lisa woke me up before dawn. It was still drizzling. The sounds of battle were barely audible in the distance. I was weak from hunger but happy to still be alive. The events of the past three days seemed remote. We thought that the Germans had probably been defeated, and I felt an overwhelming sense of free-floating gratitude and obligation for having had my life spared.

The farmer decided that it was time to move on. He strapped us to our tractor seats and we were off. As we drove along the forest roads to the highway, I was horrified by the sights. The woods and meadows were littered with the smoldering and burnt out wrecks of planes that had been shot down during the preceding three days. The same planes that had been so menacing now lay there, mere carcasses. Even in that state, I still found them frightening. Every time we passed a plane wreck I turned my eyes away for fear that I might glimpse a dead aviator. I dreaded the thought of seeing a corpse. The plane carcasses also vividly recalled for me the plane crash in Robinson a year and a half before.

“Look, Franzi, are you noticing that all of the plane wrecks are German? Lisa pointed out, always managing to put a positive slant on things.

“Yes,” I said, “Does that mean that the Germans were defeated?

“I hope so,” Lisa replied.

I was sure of it, and felt confident that we were safe again.

When we emerged from the woods and reached the highway, it was deserted. All along its edges lay burnt out tanks and other vehicles, again all of them German.

In a few minutes we came to a bombed out village in which most houses had been destroyed. The Belgian farmer stopped the truck, got out, and spoke to some local people. When he came back to the truck, he looked grim.

“The Germans are everywhere,” he reported. “They have taken over.”

My heart sank. I burst out crying. Lisa was too upset to reassure me.

“You have to get off here,” continued the farmer as he climbed up to our perches and started to untie us. “We can’t take you and the child along any more.”

Lisa argued with him and the others, but to no avail. Everybody seemed upset. Some of the women shouted at Lisa nastily, accusing her of having recklessly endangered the life of the poor child. Lisa started crying. I felt terrible that I was causing her such hardship. I thought that if she hadn’t had me with her, they would probably have let her go on with them.

They drove off without us.

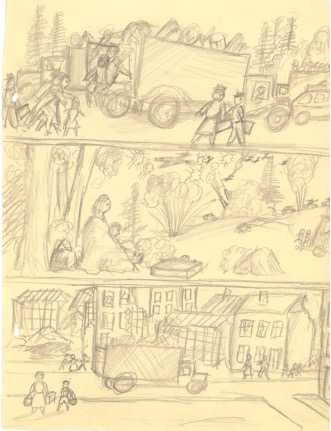

Drawings made in Havana in late 1941.

Top: Lisa and I are sitting at the back of the truck tied to the tractor, hoping to escape to Belgium. The highway is jammed with refugees.

Middle: Lisa and I are camping out in the woods for three days while the battle rages around us.

Bottom: The Belgian farmers won’t take us any farther, and we start walking through bombed-out villages.