1925

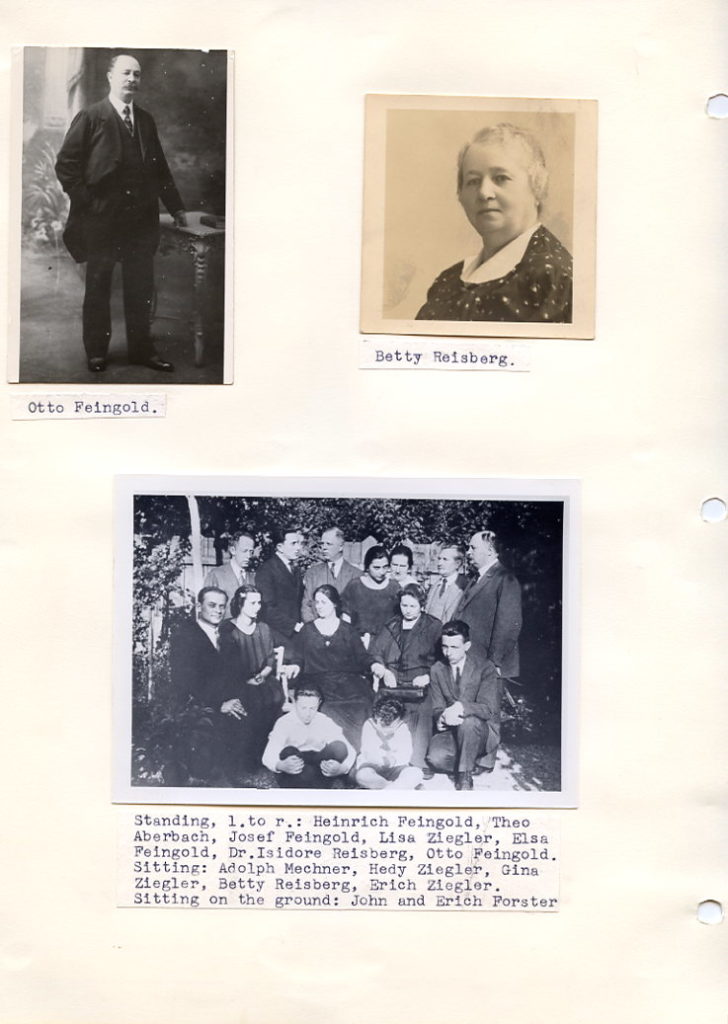

In the meantime, efforts were underway to get me the Austrian citizenship. I could have registered for the graduation, but that would have been the wrong thing to do, as I already explained before, because I would have graduated as a foreigner and could never have practiced medicine in Austria. So, I postponed it. My future father-in-law was all his life a social democrat and had among his friends and patients some influential people, who were in important positions in the local government. Through their efforts, I finally got the citizenship, and the certificate had the date of March 2nd, 1925. Immediately afterwards, I applied for the graduation, and the ceremony took place at the University on March 13th, 1925. For the same day, my engagement to Hedy was prepared, and after we returned from the University, a fine lunch was served by my future mother-in-law, with many members of the family present, including some uncles and aunts of Hedy’s. It was a nice affair, in which an uncle of Hedy, Josef Feingold, the father of John and Erich Forster, made a speech, in which he said among other things that they all were putting a jewel into my hands, to take well care of it, a speech which required a little speech also by me, for which I was not prepared and which brought at the end tears into my eyes. Everybody was elated, there was a lot of kissing and hugging going on. I was now a doctor of medicine, and not anymore a doctorandus, as which my father-in-law used to introduce me to his patients.

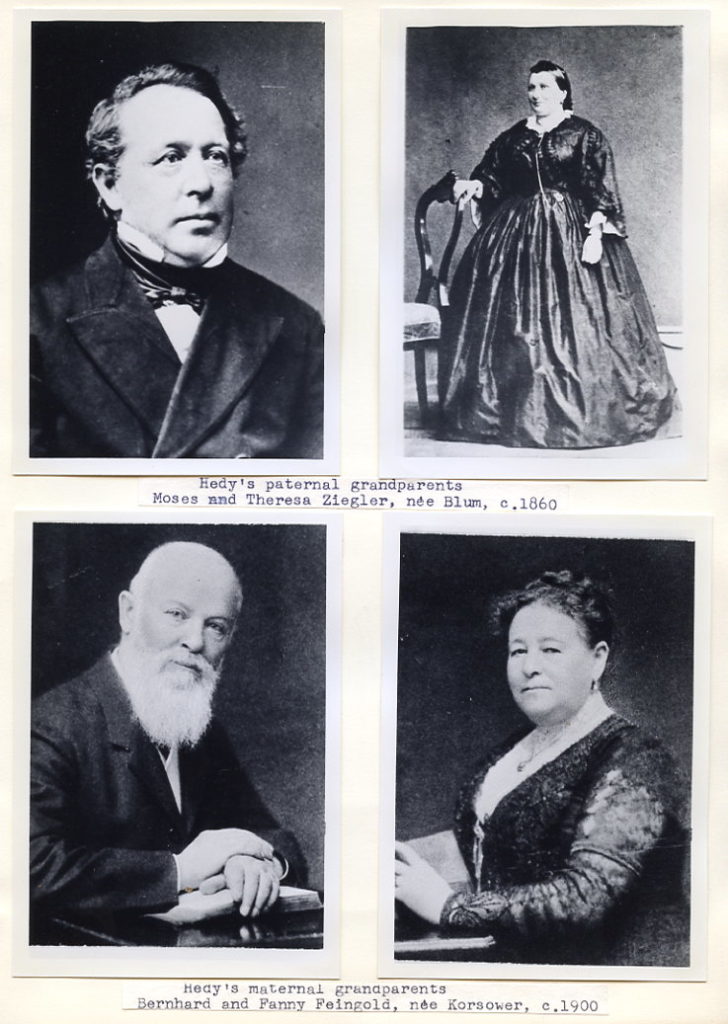

Since I was now engaged to Hedy, and was about to become a member of her family, it is appropriate that I describe her family as thoroughly as I had described my own family and that will include her grandparents on both her father’s and her mother’s side and their children and grandchildren. I will start with Hedy’s grandparents on her father’s side.

Hedy did not meet the grandparents on her father’s side, but she told me a few interesting details about them. Their names were Moses and Theresa Ziegler, nee Blum. They lived in Moravia, a province of Austria, which is now a province of Tchechoslovakia, in Gross-Meseritsch. Her grandfather was born in Neustadtl. They had 17 children and they all grew up to become successful people. Their names and the names of their husbands and wives and their children and grandchildren can be seen in chronological order in the attached family tree. The oldest son was Hermann and the youngest was Markus Ziegler.

Hedy’s father Benjamin was the 15th child. The family tree of the Zieglers was written by Lisa about 40 years ago, later readjusted by Hella Leinkauf, née Ziegler and also by Othmar Ziegler, and many names of grandchildren and great-grandchildren were added later. The names of some members could not be remembered, and the birth dates and dates of death were not exactly known and had to be left out. Copies of this biography will be sent later, when the work will be finished, to many members of the family, who are now living, and it will be up to them to continue the work up to the present time, or if they will not be interested, to leave it as it is.

Editor’s note: it is worth pausing at A. Mechner’s request, throughout this chapter and elsewhere, that this be a “living document,” to which information is continuously added by subsequent generations.

I will concentrate on one branch of the Ziegler family, Dr. Benjamin Ziegler and his wife Regina, née Feingold, and her family (I will write about that part of the family more in detail later and that alone is an enormous work). Should I die before it is finished, I hope my descendants will continue where I have stopped. Hedy’s grandfather, Moses Ziegler, died in the year 1898 and reached a very high age, about 90 years. When the youngest child, Markus, was born, it was Yom Kippur, and the mother was alone in the house, and she died on account of a hemorrhage. The grandfather remarried later. He was very religious and he had a room in his house set up for praying, like a little temple. There was much tragedy in his life too. One son, Max, was murdered in 1890 by a mad man while standing on the platform of the railway station in Kufstein in Tyrol. The grandfather was also a very charitable man who helped poor people and invited them on high holidays to participate at meals. Some of his children became very rich, some were bankers, lawyers, manufacturers, one was director of a sugar factory. When I came into the family, Hedy had about 100 cousins.

Her father [Benjamin Ziegler] had studied medicine at the University in Vienna, and he was 40 years old when he married her mother. He was 19 years older than she. He was a man of high moral principles, admired and adored by his relatives and his patients, helpful to the poor, whom he often treated without payment. He was a wonderful man and an experienced practitioner. He must have had a fine medical education, since he had a good way of examining his patients. He was generally in high esteem as a good diagnostician, and was therefore quite a busy doctor.

From the first moment I came into his house, he was extremely friendly towards me, and seemed to be proud that his daughter had found a medical student (and future doctor). In those days, doctors had to make frequently house calls, and soon he took me along when he visited patients, introducing me, as I said, as doctorandus, which means future doctor. I learnt a lot from him.

In the office, he showed me how to examine patients by percussion and auscultation. He had cases of tuberculosis, emphysema, and, of course, of congestive heart disease, and often I had to answer questions, when I hardly knew anything about anatomy. When I accompanied him on his house calls, I saw serious cases of tuberculosis, breast cancer, pemphygus, lupus erythematosus, one terminal case of melanosarcoma, leukemia, etc. He even taught me how to write prescriptions.

Very often I was unhappy, because I came to visit Hedy and he pulled me away from her, either into his office or on house calls. But what I learned from him was really invaluable. This went on for years, even when I was already a doctor of medicine. Often he sent children of poor people with a pot to Hedy’s mother for soup. He often put rolls or bread in his pockets when he went out to visit patients. He was highly educated and very good in mathematics.

Hedy’s mother, Regina, called Gina, was a fine and lovely lady, with a great sense of humor, adored by all the relatives and friends, always friendly, and her home open all the time for visitors, who were, the moment they came, invited to participate in the meals, which, since she was a wonderful cook, were exquisite. They had a nice social life, had great many friends, went out to parties, and they were well liked, wherever they went. Every summer they went with the children, when they were still small, to nice places like Voeslau, Baden bei Wien, Kochleithen, Kierling, later to the Semmering and the Salzkammergut.

Benjamin was a physician of the so-called Arbeiter-Krankenkasse, also of the Railroad workers Krankenkasse. He had the office together with the living quarters, but only one room for the office. They had once to give up one room of their apartment to a neighbor, and from then on the patients had to sit in a small hallway, since there was no waiting room anymore, and the piano had to be in the office room. But he was an unusually modest man and that did not seem to bother him, nor did the patients mind it. They all adored him and he treated them as if they would be members of his family. As a doctor, he had great knowledge and experience. When he had a serious case, he was often sitting for hours at the patient’s bedside.

His house calls he made most of the time on foot, sometimes by using the streetcar. Time and again, when I was visiting there, taking part in a meal, he called me into the office when he had an interesting case, let me examine the patient and explained the case. What I had learned from him I never could have learned from books, and long before I got my doctors degree, I knew things, which took others years to learn. He took me often along on house calls and most of his patients knew me already and later became my patients, after he retired from practice.

Here I want to insert a very special experience, which I had with a patient of my future father-in-law when I was very young, shortly after my graduation, but not practicing yet. I was visiting with Hedy, and I was about to leave for my domicile in Belvederegasse in the 4th district when a telephone call came and my father-in-law was asked to come to a patient who was seriously ill. He took off immediately and asked me to accompany him. I had my doctor’s bag with me and took it along. I remember the address, it was Pugbachgasse 10, but not anymore the name of the patient. I will call her Mrs. Meyer. We went there on foot, of course, and found there an elderly woman, in her 70s, lying on her back, unconscious, breathing heavily, and masses of pink foam coming out of her mouth and nose, the eyes open, directed upwards. The pulse could hardly be felt, but was very rapid. On ausculatation the heartbeat could not be heard, only the rattling noise of the fluid in the lungs. It was a typical case of pulmonary edema. I had ampoules of Digitalis with me and a syringe was rapidly sterilized in boiling water. My father-in-law consented that I give her an intravenous injection of Digitalis. At that time Digalen or Digipuratum was generally used.

There were many people in the apartment. This lady had 10 children, most of them married and living in Vienna, and they all kept coming in cars. One of them was a doctor, whom I knew personally. He was a prominent member of the staff of the Arbeiter-Kran-kenkasse (Workmen’s Sickness Fund), director of the prescription department. He was standing next to the bed, constantly wiping off the foam, coming out of the patient’s mouth and nose. I proposed to make a venepuncture and take out a pint of blood. This was usually done in such cases, to relieve the heart of a part of the load it had to drive, and would have helped very fast. But Dr. Meyer objected. I then proposed another Digitalis injection. He said, “Okay. But this will be the last one. I don’t want my mother to be tortured anymore. There is no help, you know it, in such a case.”

The second Digitalis injection had no effect. I had in my bag an ampoule of Strophantus, similar in its effect to Digitalis, but much stronger. I filled my syringe with Strophantus, and when I proposed it, Dr. Meyer got very angry and forbade me to do anything. The apartment was now filled with people, at least 20 were there, but not in the room where the patient was. Liquor was served and I was called to the next room and got a small glassful too. They spoke already about the funeral. They had opened the windows of the bedroom, which was usually done, when a dead person was in the room.

Dr. Meyer was busy wiping off the foam and he had also put a folded towel over the patient’s eyes, as he could not stand the fixed look of her eyes. Dr. Meyer was then also called to the next room to get a glass of liquor. I used that moment to administer the Strophantus injection, as fast as I could. I had just finished it, when he came back into the room. He shouted at me and was very angry. I could not say a word. After a short while, I felt the pulse and it seemed to get stronger. Very soon the patient moved one arm, then the other one. Then she coughed and an enormous amount of foam came out flying. She then opened her eyes wide and looked around.

All the people came into the room, shouting and shoving their happiness, getting busy with rubbing the patients arms and hands, waning her face with water and alcohol and kissing her. Dr. Meyer was not saying anything anymore. My father-in-law and I packed up our things, said “Good-bye” to everybody and left. How I got back to my domicile in the 4th district, I don’t know anymore, as the tramway was not running anymore after midnight. Perhaps I walked, as I often did before, which took about 1 hour.

Next day’s news about the patient were good. They had called the famous cardiologist professor Wenckebach for a conference—we used to call it consilium—between the 3 doctors, the professor, my father-in-law and Dr. Meyer. The professor lauded me, my father-in-law told me, and had said that in such a case the doctor never should give up, and should give many injections, till the heart finally responds.

This lady lived then 6 more years, till she died from a stroke. It was the first time that I saved a life as a doctor. It happened many times thereafter, about 8 times or 10 in the case of Mrs. Gash, Selma Freudenthal’s mother, always at night.

It so happened that I saw Dr. Meyer again many years later in Havana, Cuba. He had just come there as a refugee and he had me called to his house. He was suffering from angina pectoris and I could help him with medication. I told him that I knew him from Vienna and asked him whether he did not recognize me. I mentioned his mother and then he knew and we started to reminisce. I did not hear from him anymore.

Benjamin Ziegler was quite corpulent, bald, and had a small gray moustache. He used to walk slowly, moving from one side to the other. He rarely wore a coat in winter, but wore warm gloves on cold days. He dressed in general rather sloppily, but could dress up well, when going out in the evening to a restaurant.

That happened sometimes, and then it was a group of 3 or 4 doctors with their wives, like Dr. and Mrs. Koch, Dr. and Mrs. Wolken, Dr. and Mrs. Sternberg, and others. I was a frequent participant, and at the end one of them paid the entire bill, often enough my father-in-law.

He liked good food and my mother-in-law did her best to satisfy him. He was careful with money and did not like it when she put too many things on the table, but what she did was always excellent. He always was very economical and tried to be an example of it to others. It was a rule that everybody ate all there was on the plate, and there were never leftovers to be thrown away. But in general, he was noble end was respected for it. He did not allow harsh words or gossip, and treated his children with respect, also the young people, who came into the house. Straightforwardness was one of his most important characteristics, and he demanded it also from others.

I remember a scene, when we were once sitting together, on a day when he had received a bigger cash payment from a patient. He put it on purpose into his breast pocket in such a way that a few bills stuck out a little. My mother-in-law saw it and said, “What do I see here?” and pulled the money out. He pretended anger, but soon laughed, too, with all the others. That was one special way of giving money to her for shopping. He did not have an easy life. There was the family and often, very often, visitors, including me. He was a good chess player and a great mathematician. He disliked people who were not only not poor, but who were, as we say, comfortable and still tried to take advantage of him or other people. For them he had a special expression: Dreckfresser, which means something like eaters of excrements, just as he called people who liked to swallow large numbers of pills: Pillenfresser.

And he strongly disliked people who smelled from perfume. When such a person sat down next to him in a streetcar, he moved away from her as far as possible, holding his nose tightly closed with two fingers, so that that person would possibly understand why he had moved away. And he also disliked women who were snobbish and showed off with much jewelry on their dresses, hands, and ears, and was especially angry when Jewish women were sitting with much jewelry on them in the coffee-houses on open terraces, at a time when antisemitism was growing. He used to say, “The Jews will see one day what will happen to them.” How right he was! The Nazis finally came.

We come now to Hedy’s grandparents on her mother’s side. Their names were Bernhard and Fanny Feingold, nee Korsower. I knew them too. The grandfather was in the jewelry business, specializing in pearls. He was a very religious man, very strict, and adored by the family. They had 6 children. The oldest son was Otto Feingold, who lived in Paris, where he had married a French woman, Louise Zimmermann, who was not Jewish, but had converted to Judaism. She adored her husband’s parents and did everything to please them, kept the Jewish holidays strictly, and brought their two children up in the Jewish faith. Otto was also in the jewelry business and was very successful. They had a home in the country near Paris in Neuilly Pleasance. The son, Raymond, was married to Lucy Werdenshlag.

I met them in Paris in 1938, when I was there on my way to Cuba. They were lovely people. Raymond survived the war, was in the army, was taken prisoner by the Germans, while in Paris. There Suzanne, his sister, literally saved his life by changing the name on his identification card from Feingold to Fingol, so that the Germans could not find out that he was Jewish. He was then taken to a prisoner camp in Germany, but managed to escape and to make his way back to France into the unoccupied zone. Unfortunately, he lost his life a few years later in an automobile accident. Suzanne married as a young girl a Mr. Roger Levier, very much against the wishes of her parents. She had a child, Nicole, who was born mentally retarded. The marriage did not last long.

During the Second World War Suzanne worked in the French underground, where she met Mr. Kenri Archambould de Monfort, a count, and his wife. The wife was captured by the Germans and killed. Suzanne and M. de Monfort got married after the war. He was very rich, was at one time secretary of the Institute France, also wrote a few books about Polish history. They had a wonderful house in Paris with many very valuable art objects. They owned a French newspaper, which gave them a big income, and also owned a house on the French Riviera in Agay between St. Tropez and Nice. We were once for one week their guests there. Henri died about 10 years ago, and Suzanne half a year ago, and Nicole, her daughter, is in Paris; also Lucy, the widow of Raymond.

We come now to the second branch of the Feingold family: Betty, who was married to Dr. Isidore Reisberg, a physician, who had his office in the second district in Vienna, and later moved to the outskirts to Ober St. Veit. They had 3 children, a daughter Johanna, who studied medicine in Vienna, became a doctor and specialized in gynecology and obstetrics. She married an American physician, Dr. Abraham Hilkowich, who was also a gynecologist and obstetrician, and moved to New York, where they had their office in Manhattan at 315 Central Park West. They had 2 children, Ita and David. Dr. Hilkowich died during the war. Johanna got then a position as a physician in the House of Detention for Women in New York, which she kept for over 20 years. Her daughter Ita married a Mr. Mallon, with whom she had one child, Vicki. But the marriage ended in divorce. Ita became then a teacher and still teaches biology in high school. She later remarried a Mr. Kurt Charles Louda, and they live in the same building at 315 Central Park West in a beautiful apartment, overlooking Central Park. They later had a child, Robert Louda, who is now a handsome young fellow of 17. They also had a house constructed way up in the country, in Granville near Lake St. George, to which they go on weekends, summer and winter. Vicki, their daughter, teaches in grammar school, and got married on January 15, 1977, to a young man, Mr.Gary Gleicher. Johanna Hilkowich died at the age of 80, about 2 years ago. The second child of Johanna Hilkowich, David, who had changed his name to Hill, is married to Sydelle, nee Pollack. They live in New Jersey and have three children, Jonathan Andrew, Douglas Allen, and Linda Ann. David was a stock market analyst, and is now doing statistical work with a large construction firm, and Sydelle is working with an importing company.

The Dr. Reisbergs had, as I said, besides Johanna, two more children, a son Marcell Reisberg, who was married to Margitta, and they lived in California. He died there, many years ago, had a lung cancer. And the third child of the Dr. Reisbergs, is Gertrude, who lives in upper Manhattan near us. She was never married, and supported herself well, working in different positions, at the end for many years at the Western Union.

The family story of Dr. Isidore Reisberg and his wife Betty is not known to me well enough. I hope that Ita and Kurt Louda and David Hill will find it worthwhile to continue here and add more details about these ancestors as well as about themselves, and perhaps Kurt Louda and Sydelle may want to add their own biographies too.

Now to the third branch of the Feingold family, Josef. He was a lawyer and had his office in Vienna in the Beatrixgasse in the 3rd district. He was married to Elsa, nee Schaefer, and they had a beautiful house in Baumgarten on the outskirts of Vienna. They had two children, John and Erich, who later changed their names to Forster. After the Hitler invasion of Austria they emigrated to France. But the parents and Erich were taken by the Germans to Poland, where the parents perished, while Erich survived and later came to the United States. John married Stella, nee Wagner in Vienna, and they later also came to the United States. Their story is very complicated and fascinating, and I will never be able to tell it correctly. I hope that John and Erich will continue here, perhaps change and rewrite in detail what I have written so far about them. It should be a fascinating story that Erich especially has to tell about his escape from captivity, also how he came to the United States. John and Stella have three children, Lynn, Jimmy, and Lisbeth, all three married and they have little children, and Eric and his wife Erna have 6 children, and live in Scotch Plains in New Jersey, a lovely, happy family, and John and Stella live in Harrison, New York, and have good reasons to be content and happy with their family.

The fourth branch of the Feingold family was Susi, who was also married to a physician, Dr. Osias Pariser, who had his office in Hohenau, north of Vienna, near the border of Moravia. He had died of a brain tumor, and Susi moved then to her parents in Vienna with her two children Annie and Kurt. Annie was the girl who introduced me to Hedy. Annie was an excellent dancer, and it was in a dancing school that I met Hedy the first time. She later went with her uncle Josef and aunt Elsa on a vacation trip to the Baltic Sea, where she met her later husband, Max Lux, who had a big store in Berlin. After they got married, they settled in Berlin and had one child, Ellen. They had there a wonderful life together, till the Hitlerism started. They had to give up everything and moved to Amsterdam. Later, when the Nazis invaded Austria, Susi joined them in Amsterdam. The rest of the story is very sad: They were all taken to the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen in Germany, where Susi and Max died. Annie and Ellen survived, and went back after the war to Amsterdam, where they still live. Annie’s brother Kurt was also a Hitler victim. But his daughter Gerty survived miraculously, later got married, and we once got a letter from her from Kenya in Africa. We never heard from her again. Hedy and I visited Annie and her daughter Ellen in Amsterdam in 1960, and spent a few pleasant days together.

The fifth branch of the Feingold family is Gina, Hedy’s mother, and I have written about her already and will write a lot more. The sixth branch was Heinrich. He had lived for many years in Panama and also in Paris, and was in the pearl business. He returned to Vienna, and married Hella, nee Aberbach, and they lived in the apartment of his sister Susi for many years. They had no children. When the Nazis came, they managed to escape illegally over the Belgian border and. lived in Brussels during the war, suffering much hardship, but survived. Heini, as he was called, died in the year 1958, and Hella still lives in Brussels. We visited her once there in 1960.

I noticed that I had not said anything about Mrs. Fannie Feingold, the wife of Hedy’s grandfather Bernhard Feingold, had only mentioned her name and her maiden name Blum. I saw her a few times. She was completely blind for many years, as the result of a stroke, and they had a nurse in the house to help her for many years. Both Bernhard and Fannie Feingold died in 1922, 14 days apart. They had raised a noble, fine family.

I should also add that Betty Reisberg, the oldest daughter of the Feingold family, had left Vienna and came to the U.S. with her daughter Gertrude at the end of November 1938. Betty died on January 30th, 1945, 77 years old. Her oldest daughter, Dr. Johanna Hilkowich died on December 11th, 1973, shortly before reaching the age of 81 years. Her brother Marcel had died in 1948.

I should furthermore add that Suzanne, the daughter of Otto Feingold, died in 1977, 73 years old, and had suffered from diabetes.