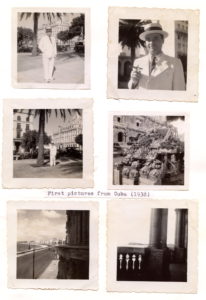

1938

A few days later, we were in Havana, Cuba. The whole voyage had taken 14 days. The disembarkation took a very long time, as an officer of the immigration department examined the papers of each passenger very thoroughly. While this was going on, a man from the Joint Distribution Committee came on board and explained the situation in which refugees from Europe would find themselves in Cuba, and what the chances of getting visas for the immigration to the United States were. He explained the quota system and the waiting period for people from different countries of origin. For me, this man had very bad news. I had expected that I would have to wait a few weeks or perhaps months, but he told me that it would take years since I was born in Rumania, and the Rumanian quota was very small, only 375 per year. I was shocked, and fell for the next few days into deep despair. All my planes had suddenly come to naught.

For the first night I went together with some people I had befriended with on the boat to a hotel in the old city of Havana, at the corner of Calle Obispo and Calle Cuba. I woke up early on account of enormous noise by a streetcar, which passed near the hotel through a narrow street, autos, and vendors. My friends and I went in the morning to look for other quarters and we found a nice rooming house on the Prado, a wide boulevard with an alley with trees. I got a room, which I was to share with a man I knew from the boat, a Mr. Oling, who came from Berlin. It was a different world which I had not known before. I was not completely unprepared, since I had gone on land a few days before in three different Latin American cities: San Juan in Puerto Rico, San Domingo in the Dominican Republic, and Port au Prince in Haiti, all of them big cities, though each quite different in appearance. Very similar were the large noisy crowds in San Juan and Port au Prince, the great number of black people, the many vendors. Havana was much larger, also full of life, and noisy, and in many respects more beautiful, with its boulevards, parks, and many imposing, big buildings, old, but impressing in style. Very beautiful the Malecon, a long avenue along the seashore and near the entrance to the port, running along a wide canal between the city and a peninsula with the old Castle Moro.

I became very soon acclimatized and found my way around. I had learned Spanish while still in Vienna, with the help of Heini, Hedy’s uncle, who had lived for many years in Panama, and who had come almost daily to give me lessons, altogether about 20 times. And while on the boat, I gained good Spanish grammar, and tried to acquire more knowledge of that language. Having a talent for languages, I was soon able to talk and understand people.

I went to the American consulate to ask about my chances of getting an American immigration visa. The answer was as devastating as the information I got on the boat when it arrived in Havana: many years of waiting. That threw me again into despair and depression. I could figure it out myself that I would have to wait many years on account of the Rumanian quota. I had applied for immigration at the consulate in Vienna in June 1918. There were so many people ahead of me, Rumanians still in Rumania, and the many Rumanians living in many countries in the world, in Austria, Germany, Poland, Hungary, and elsewhere. The number was in the hundred thousands, and I was told that it might take as long as 80 years till my name would be at the top of the list.

I spoke with many people about my situation and also, among other things, about my invention of Viperin. Some of them thought that this might help me get the immigration visa. That gave me a little hope and I thought much about it.

I had another problem: living expenses. I had brought with me only 420 dollars, and it was obvious that this small amount of money would not last very long. It had shrunk already considerably. My roommate, Mr. Oling, asked me one day about my financial situation. He had thought that I must have a lot of money, since I was dressed neatly, was wearing a fine white suit, had fine shirts, etc. I told him the truth and he was amazed at how little I had. He advised me to go the next day to the refugee committee like most of the others and ask to be enrolled, which I did. From then on, I received regular support money and my worries about money came to an end. I could even save a little money and put it in the bank. Every two or three days I went to the bank and took out 5 or 10 dollars, rarely more. It was enough for the coffeehouse in the morning and for the restaurant at noon and in the evening, also for the wonderful fruit I bought every day, for the movie theatre in the evening, for the laundry man, newspaper, postage, for the development of films and prints, great numbers of them, and, of course, for rent. Everything was cheap and I could afford it.

It did not take long for me to get some patients, refugees who needed advice, and I earned a few dollars. And there was a druggist who filled my prescriptions given over the phone, delivered them even to the homes. My fee was small, usually 1 to 2 dollars for a house call, seldom more. I was satisfied.

I had taken with me to Cuba the name and address of a Mr. Alberto Johnson, who was an importer of medicines from many European countries. I was told that he might be interested in distributing Viperin in Cuba. So I went to him soon after my arrival in Havana. He was a fine gentleman and showed great interest in Viperin. He had two brothers who had an enormous drugstore under the name Johnson & Johnson, the second largest in Cuba, and he introduced me to one of his brothers, Dr. Carlos Johnson. We had long discussions about Viperin and the possibility of manufacturing and distributing it in Cuba. They decided that they themselves would not undertake it, but that they knew of other companies which would do it. I told them that I had to do some experimental work before doing anything else and they recommended me to a man who had a big medical laboratory, one of the biggest in Havana, This man was very friendly and obliging and told me that I could use his laboratory whenever I wanted and for any kind of experimental work.

What I had to do were experiments on mice, in the first place to find out the number of mouse units that went into one gram of ointment. The powder which I had taken along from Vienna was supposed to contain in one gram the amount of snake venom that went into 5 grams of ointment. I had to find out whether that information was correct. Later on, I would have to find a snake venom that would replace the snake venom which we had used in Europe, which was the venom of vipera ammodytes, a snake that is very common in Yugoslavia and other Balkan countries.

I will now leave the story of my experimental work, will later come back to it, since important things that happened in the meantime have to be described.

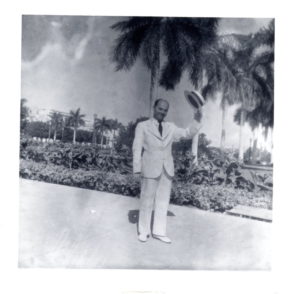

I was receiving letters from Hedy and also from Lisa and Francis, and I had written to them frequently; pictures, which I had sent them, showing me in a white suit with a straw hat seemed to have impressed them very much.

In one of the letters Hedy wrote that the Nazis had come to look for me on the day after the so-called Crystal-Night from the 9th to the 10th of November 1938, when they set on fire 17 temples and 6l houses of prayer in Vienna and the other cities in Austria and had arrested and sent to concentration camps 7,800 Jews. In Germany they had also destroyed by fire innumerous temples and arrested 26,000 Jews. That was 40 days, after I had left Vienna. How lucky I was!

In one of the letters Hedy wrote that the Nazis had come to look for me on the day after the so-called Crystal-Night from the 9th to the 10th of November 1938, when they set on fire 17 temples and 6l houses of prayer in Vienna and the other cities in Austria and had arrested and sent to concentration camps 7,800 Jews. In Germany they had also destroyed by fire innumerous temples and arrested 26,000 Jews. That was 40 days, after I had left Vienna. How lucky I was!

Hedy had a hard time there, all alone in the apartment with Johanna and her parents nearby, since restrictions for Jews became stricter and life almost unbearable. This is well described by Hedy in an interview, which will be attached here. We had hoped that she would get her American visa soon after I left, we thought within 3 or 4 months, but it took more than a year till the American consul gave her the visa. In the meantime she had to handle the packing of the furniture and all our belongings into a lift van and then to move to the apartment of her parents. She was threatened by the Gestapo frequently with being sent to Poland if she does not leave soon. But how could she without a visa? What Lisa and Francis went through, is also well described in interviews with them, and will be attached later, to give you a first-hand description and well-rounded picture of their lives. This will allow me to restrict myself to describing how I fared in Cuba.

I should, for instance, mention that about two weeks after my arrival in Havana, Leo and Ella Ziegler arrived there also. Before I had left Vienna, I saw them and told them that I am going to Cuba. They were astonished, but did not say a word that they would also be going to Cuba 14 days later. They kept it as a secret, probably in fear that the Germans might learn about their departure and somehow interfere with their plans. Anyway, I learned about their arrival through Ella’s brother, Maurice Ziegler, who was already in New York, and I went to the boat when it arrived. Although my Spanish was not yet good, I intervened on their behalf, using all kinds of excuses and explanations, and finally succeeded in freeing them so that they could leave the boat instead of being sent to the camp Tiscornia for quarantine like all the others. They were very happy about it. I had prepared a hotel room for them and, instead of flowers, a basket full of fruits. A few days later, I took them to the Malecon, where they found a nice little apartment where they stayed for many months. We often met in their apartment, a few times went on small excursions, often met in a little Chinese restaurant for lunch. Ella got her visa for the United States earlier than Leo, perhaps because she was born in Egypt and a visa number was free at that time for that quota, and she joined her father Marcus Ziegler in Chicago. Leo had to wait a few months longer, had rented a little room somewhere in Vedado, a suburb of Havana. Leo had a talent for painting and went almost daily out with an easel and canvas to paint, always aquarells. Some were quite good, and with the help of Ella, while she was there, he framed a great number of them and once arranged an exposition in the lobby of a big hotel, and sold a few of them. Ella worked in Chicago as a maid in a hotel, had to wash bathrooms and scrub floors, worked very hard. Later Maurice settled in Los Angeles and when Leo arrived in the United States, he made arrangements for Leo and Ella to settle in California too. They wanted to settle in a place far from a big city and they bought, high up in Santa Ynez, a dilapidated farmhouse and farmland with a chicken farm. They remodeled the house nicely, planted great many walnut trees, which would bear nuts in about 4 or 5 years, and in the meantime raised and handled about 2,000 chickens and sold the eggs. They lived not only on the gains from the chicken farm. Leo got a position as an art teacher at four different high schools. They bought a little car and he learned how to drive, and he drove every day from one high school to another, and he worked and earned a living this way till he died at the age of 8l or 82, some 10 or 12 years ago. Ella still lives there, about 80 years old. She once was a real beauty, and still shows it. We had visited them there three times, once with Nancy [Cooper]. I write all this to show a real success story of two refugees from Europe.

Leo had a talent for painting and went almost daily out with an easel and canvas to paint, always aquarells. Some were quite good, and with the help of Ella, while she was there, he framed a great number of them and once arranged an exposition in the lobby of a big hotel, and sold a few of them. Ella worked in Chicago as a maid in a hotel, had to wash bathrooms and scrub floors, worked very hard. Later Maurice settled in Los Angeles and when Leo arrived in the United States, he made arrangements for Leo and Ella to settle in California too. They wanted to settle in a place far from a big city and they bought, high up in Santa Ynez, a dilapidated farmhouse and farmland with a chicken farm. They remodeled the house nicely, planted great many walnut trees, which would bear nuts in about 4 or 5 years, and in the meantime raised and handled about 2,000 chickens and sold the eggs. They lived not only on the gains from the chicken farm. Leo got a position as an art teacher at four different high schools. They bought a little car and he learned how to drive, and he drove every day from one high school to another, and he worked and earned a living this way till he died at the age of 8l or 82, some 10 or 12 years ago. Ella still lives there, about 80 years old. She once was a real beauty, and still shows it. We had visited them there three times, once with Nancy [Cooper]. I write all this to show a real success story of two refugees from Europe. Now back to me in Havana. I should mention that I was there in the middle of a bunch of young and middle-aged men, who met almost every evening at a rendezvous place on the Prado, a promenade with many coffeehouses on wide terraces, where there was always music being played, across the street from the beautiful capitol. Great numbers of people were sitting there or promenading till late at night. Mr. Oling, my roommate, and another one friend, Mr. Kolitz were the only ones whom I later met in New York, and we remained friends and see each other quite often. There was also a Mr. Luxemburg, a very fine fellow, a Mr. Herrnstadt, a Mr. Kreuzberger, and a few others whose names I have forgotten. When I missed them at our rendezvous place, which happened a few times when they had gone to a movie without me, I was quite disappointed and felt lost, and went to my room to read or write letters.

Now back to me in Havana. I should mention that I was there in the middle of a bunch of young and middle-aged men, who met almost every evening at a rendezvous place on the Prado, a promenade with many coffeehouses on wide terraces, where there was always music being played, across the street from the beautiful capitol. Great numbers of people were sitting there or promenading till late at night. Mr. Oling, my roommate, and another one friend, Mr. Kolitz were the only ones whom I later met in New York, and we remained friends and see each other quite often. There was also a Mr. Luxemburg, a very fine fellow, a Mr. Herrnstadt, a Mr. Kreuzberger, and a few others whose names I have forgotten. When I missed them at our rendezvous place, which happened a few times when they had gone to a movie without me, I was quite disappointed and felt lost, and went to my room to read or write letters.

I was sitting at my typewriter all the time, during the day and often till late at night, writing letters. But evenings I liked to be with these people, discussing the news, getting opinions. Often we gathered around a table to play cards, usually poker, for money, which was fun. There came New Years Eve, when the whole group of us went to the casino where there was a big celebration, all of us wearing tuxedos. And then came carnival time, celebrated on the Prado and Malecon with big parades, quite an event in Havana.

I should also mention that I was taken to butterfly hunting in Havana, in a special way. Since I had no net, I used to hit the butterflies with my stiff straw hat and pick them up from the ground, kept only those which were not too badly damaged. In this way I got a small collection together. Once I had sent a wooden cigar box with butterflies to Francis with pieces of cork glued in to hold the pins. I was careful and had put the pins in firmly, had selected really beautiful specimens. But unfortunately, they arrived in France completely destroyed, probably because the box was thrown and hit hard in post offices and during the voyage on the boat. Francis was disappointed, but at least he saw the good will. I received from him quite a few painted postcards which showed birds or butterflies, which I had in my room, posted on the Vail. I have a collection of letters, written by Francis, and I had given most of them to Francis, some time ago, also many drawings and paintings.

I am here attaching two of his letters. The first was written on or about December 13, 1938, exactly 2 months after I had left him in France, when he was 7 1/2 years old, written in German. I am giving here the translation into English:

Yesterday there was a cat in the garden. And just then it rained and the door of the house was already closed because it was already night. The cat had cried all the time. I am very well here. I am going now into a children’s home, but only in the afternoon and only on Monday, Tuesday, and Friday. I did not wait for any letter. I am sorry for you because you have to work so hard. The butterfly arrived completely squashed. If you send me again one, then put it into a box. I have not been yet to Snow-White, but instead of that I got a book from Mrs. Dr. Saxel. I am very happy with the two big beautiful butterflies. I will send you with this letter a drawing. I received from Vienna the calculating machine. Lisa received also from Vienna two pictures of Hannerl; I would like to send them to you, but Lisa would not let me have them. How are you? Send also to Mr. Streitz a few butterflies. When will you go to America? Let’s hope very soon. Have you seen already butterflies as big as this letterpaper?

Many kisses from Franzi.

The second letter was written on February 1, 1939, and here is the translation into English:

Dear Papa!

I have slept today the first time in our new apartment. Today I am staying the whole half afternoon in the hotel Scribe, while Lisa is giving a lesson. How are you? I am very well. Have you already been on a crocodile hunt? Have you already watched how they catch sharks?

I have 89 francs and for 12 francs I had bought something for Suzanne. She has today a birthday. We eat every Wednesday at Lucy’s. For tomorrow we are invited to Jaquot (he is a nephew of Lucy). I am very glad. We will go up to the top of the Eiffel Tower. I will make an airplane for myself, which will really fly.

I send regards to Aunt Ella and Uncle Leo and kisses and for you many kisses from me.

February, 1939

Franzi.

Two more letters, written later, will be inserted later on.

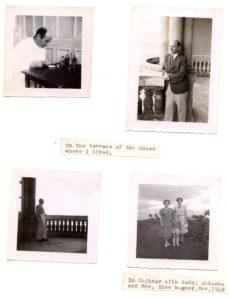

After my roommate, Mr. Oling, had moved out, I got for a short time another roommate, a Mr. Barasch, and following him, again another one, a Mr. Platschek, a very fine guy. Soon afterwards, he found a rooming house on the Malecon, and we both moved there, had two separate rooms and all meals there at a modest price. It was a fine house, at the corner of Galle Lealtad, with a big terrace and a view of the ocean and further to the right of the Gastel Morro, where I could watch the boats coming from Florida, also the daily ferryboats, loaded with trains. Sitting on the terrace was quite a pleasure. I had made a good change.

I should mention here that at about that time I got a letter from Julius Ziegler, in which he wrote that a Mrs. Else Wagner will arrive on a certain day in Havana, and he asked me to help her, as much as I could, to get established in Havana. She was a very nice, fine lady, about at least 10 or 20 years older than I, and we became good friends. She was never married, was the lifelong friend of Julius Ziegler’s former boss, a Mr. Spielmann. Mr. Spielmann’s two sons, both homosexuals, came later also to Havana and we met often in coffeehouses. Later, when Hedy and Johanna came to Havana, we still met Mrs. Wagner, and Hedy seemed to like her. Soon afterwards, Mrs. Wagner got her visa for the United States, where Mr. Spielmann had already arrived, and they both settled in Miami.

In the meantime, I received from Hedy the good news that the lift van had been packed and sent to Hamburg. This was at the beginning of the summer of 1939, and at about that time Lisa had sent Francis for the summer to friends in Le Touquet-Paris Plage on the English Channel, who were taking care of other children too, and where he had it very good. Lisa had started working in Paris for Raymond. This was relatively good news.

But the general situation in the world grew worse with each day. Hitler, after having taken over the Sudetenland, succeeded soon in taking over the rest of Tchechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, incorporating it into Germany as a protectorate. Slovakia and the Carpatho-Ukraine became independent, but soon were put by Tito, who headed the state, also under German protection. The German colossus had become enormously big.

It did not take long and Poland appeared to become the next victim. Starting with a barrage of threats in speeches and in the press, Hitler told the world clearly what would come next. Faced by the prospect of limitless German expansion, the British and French pledged aid to the Poles in case of action threatening Polish independence. The British made also every effort to draw Russia into the anti-aggression front, but the Russians were suspicious and insisted on complete reciprocity in defense.

On August 20, the world was startled by the conclusion of a trade treaty between Germany and Russia, followed the next day by the announcement that Germany and Russia were about to conclude a nonaggression pact. Coming after months of negotiation between England, France, and Russia, this move was regarded as a demonstration of Bolshevik perfidy. In England and France, as well as in Germany, military preparations started. The British government reiterated its pledge to Poland. The German-Russian pact was signed in Moscow by the German foreign minister Ribbentropp and then on August 23 in Berlin by Molotov, the Russian foreign minister.