1939

Anyway, I was happy to learn that Hedy and Johanna had left by boat from Rotterdam–it was on the 12th of December, 1939–and that they had safely arrived in New York, 12 days later. I had written in the meantime to Hedy’s cousin, Dr. Johanna Hilkowicz, and had asked her to rent a little apartment for them, and that she should put there in a vase a bunch of flowers. I also sent her a check of $30 to give to Hedy, so that she would have a little money right away. That was probably all I had at that time.

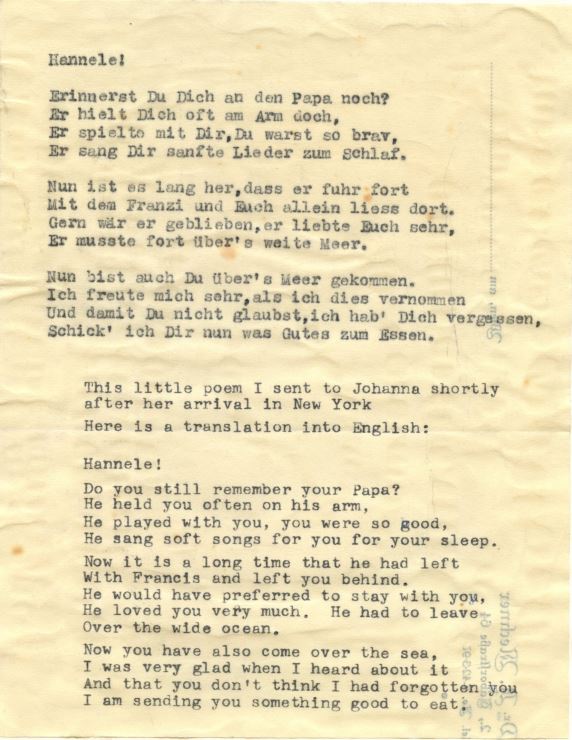

From then on, I was in constant contact with Hedy by mail. She had a little furnished apartment on West 89th Street near Central Park West.

The details of Hedy’s life in Vienna after I had left, her departure, voyage, arrival in New York, and life afterwards are described by her in an interview, which will be attached here, also interviews with Lisa, Francis, and Johanna. This will give a well rounded picture of their lives, seen from different angles. I also had the opportunity for an interview with Lisl Ziegler, when she was in New York in November 1976, which will give an interesting description of her and Erich’s experiences from the time they had left Vienna, each separately, got together in Brussels, where they got married, their voyage to Australia, and their life there with their family. Also an interview with my brother Walter, in which he described the situation of my family in Czernowitz, his departure to Argentina in 1938, his life there, his marriage with Fanny, their struggle there together with their son Hugo, and finally their arrival in the United States, about 10 years ago, and their life here since then. All that should provide interesting reading and detailed information about my family, and make it easier for me to continue with my own story.

When the war had started, I had another worry, the lift-van, which was in Hamburg. I wanted to save it, get it out from there. I wrote to the forwarding agent, the company Leinkauf in Vienna, and asked them to have the liftvan moved by rail from Hamburg to Trieste in Italy, and to use the money, which I had paid them for the transportation by sea from Hamburg to New York for the moving of the liftvan by rail. That was done in a relatively short time, and I was notified that the liftvan had arrived in Trieste.

It should be mentioned here that Hedy’s parents had stayed in their apartment, after Hedy and Johanna had left, for a while longer. But afterwards they had to move. They got an apartment in Hollandstrasse 9, also in the 2nd district. It happened to be a relatively nice apartment. In the same house lived two relatives, my father-in-laws sister Klementine Husserl, called Klemi, and a sister-in-law Rosa Ziegler, widow of Jakob Ziegler, with her daughter Hilda. They had sent us pictures, showing them sitting peacefully together, drinking coffee, also one with aunt Klemi and aunt Elsa Ziegler, widow of Siegmund Ziegler, mother of Trude, Klara, Emmy, and Walter.

After the occupation of Poland by Germany and Russia there seemed to be a lull in the war. It was a formidable task for the Germans to digest the territory and organize themselves in Poland. In the meantime, on November 30th, the Russian army attacked Finland, opening the Russo-Finnish war. The Finnish army put up a strong defense, but after a few months of varying success the Russians succeeded in breaking through the Mannerheim Line. A peace agreement, negotiated in Moscow, meant for Finland the loss of big chunks of territory in the East, including the city of Viborg and far in the North the port of Petsamo and adjacent territory.

Then, on April 9th, 1940, Germany occupied Denmark, which did not offer any resistance, and at the same time invaded Norway. In Norway there was resistance, but after a few weeks the whole country was occupied. King Haakon VII. and his cabinet had escaped to London. Before the occupation of Norway was completed, the German army on May 10th, without warning, invaded Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

On that same day, Winston Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as British prime minister. The French and British governments dispatched expeditionary forces into Belgium to cooperate with the Belgian army in its resistance. On May 12 the German army crossed the Meuse at Sedan. On May 12th Rotterdam surrendered to the Germans, after part of the city had been destroyed by an exterminating air attack. Queen Wilhelmina and her government escaped to London and the Netherlands army capitulated on May 14th. German mechanized divisions drove deep into Northern France, racing to the English Channel at Abbeville, thereby cutting off the northern part of France, and thus separating the British and Belgian forces from the main French armies. The Belgian armies had to fall back upon Ostende and Dunkerque, and King Leopold III on May 26th ordered them to capitulate. The British expeditionary force of some 250,000 men had to be withdrawn by sea, chiefly from the beaches of Dunkerque. About 215,000 British and 120,000 French troops were rescued by heroic efforts, but had to abandon almost all equipment.

This was happening while Lisa and Francis were in that same area, which was cut off from the rest of France. Their experience at that time is vividly described in interviews by Lisa and Francis. I, in Cuba, and Hedy, in New York, went through days of agony when learning the news. I remember that I had looked anxiously at the map of France, had foreseen the disaster and had hoped that they were able to escape in time to Abbeville, which was only about 30 miles from Le Touquet. But no, they had left too late, when the bridge over the Somme river was already destroyed, and the Germans had already advanced along the coast towards Boulogne, passing through LeTououet. For months afterwards we were cut off from them and did not know, whether they were still alive. Later we had found out through Hedy’s parents in Vienna that they had received mail from them and that they were O.K.

Hedy had hard times in New York, had to work to earn a living and to take care of her little girl and her little household. And all the time, since she had arrived in New York, she had tried to get an affidavit for her parents in Vienna. One man, a Mr. Max Bruell, very wealthy, a brother of Hedy’s cousin Samuel Bruell, had promised her an affidavit, but in the end reneged, and she had to start again to find somebody. A young woman, a physician, Dr. Runes, had promised Hedy’s parents in Vienna that her relatives would send them an affidavit from New York. She needed money for the ticket for the boat, and Hedy’s parents helped her by lending her the money. Hedy had a difficult time with that Dr. Runes in New York. She could seldom reach her by phone, and she finally told her that the affidavit was sent to the American consulate in Vienna. But it was never confirmed by Hedy’s parents, and Hedy had to assume that it was never sent. Only recently, after 35 years, copies of documents, which Hedy’s parents lad left behind in Poland, were sent to us, and among them was a letter from the American consulate, which showed that the relatives of Dr. Runes had really made out and sent the affidavit to the consulate in the summer of 1940. But it was written in such a way that the consulate could not be sure that they would really help them, if they would come to the United States, and wanted additional reassurance from the people, who had written the affidavit. To get an additional letter from these people was apparently not possible. Hedy’s parents had asked Marianne Erdstein to intervene with Dr. Runes, but these people were not willing to do anything, and on account of that two wonderful people lost their lives. Why Hedy’s parents never wrote Hedy or me about it, is difficult to understand. It could be that they did it and that the letter got lost.

As I saw that Hedy was unsuccessful in finding somebody, who would be willing to write an affidavit for her parents, I urged her to leave New York and join me in Cuba. I had become very impatient, had also spoken with her by telephone, and she finally gave in.

Adolph writes: “For months afterwards we were cut off from them and did not know, whether they were still alive. Later we had found out through Hedy’s parents in Vienna that they had received mail from them and that they were O.K.” My dad doesn’t think it’s likely that Lisa would have been able to get word to the grandparents that they had returned to Le Touquet and were OK, until much later, after they were out of the occupied zone, in Vichy or even in Nice; and that when Adolph writes (in the next chapter) that he believed they were safe in Le Touquet, he means he believed they were safe before the German invasion.