1910

In the meantime I had progressed well in school. I liked very much Latin and Greek, but I was most interested in zoology. To the hobby of collecting butterflies and other insects had come other hobbies — collecting minerals, stamps, and photography. I had started with photography very early, when I was about 11 or 12 years old. I had a very primitive camera with a wooden tripod, a box with a lens with a fixed focus 8. In the back was an opalescent glass in a slot, which could be taken out, and into which a cassette could be slid in, which contained two glass negatives. The distance between lens and glass negative could not be changed. To take a picture, I had to cover the lens with a cap. The exposure took about 10 seconds. I removed the cap from the lens and counted slowly till 10. During that time the person whose picture I took had to sit absolutely quiet and not to blink, otherwise I had to repeat the process. I developed the negative in our cellar. Prints I made by using a paper, which was not very light-sensitive, in exposing it to daylight in a frame for quite a long time, and developing it then in a similar way I developed the glass film. It was a rather simple method, and the results were often amazingly good. I photographed most of the time Walter, who was a really lovely and charming child. Unfortunately, all of these pictures were lost during the First World War.

I had my own room in our house, which was like a museum. I had found a man who was a professional taxidermist, and I was sitting often for hours in his house, watching how he stuffed all kinds of animals, mostly birds, also heads of deer, which he mounted on boards to be hung on the wall. He was an excellent expert and did everything with great skill. I bought often birds from him, which he could sell only if they were left and not claimed for one or two years. I had in my room a buzzard, a bird of pray, a little smaller than an eagle, a big owl, a falcon, a giant crow (in Latin corvus corax), which became later almost extinct in all of Europe, many other birds like the blue jay, also a white baby rabbit, also a skeleton of a cat, and great many smaller birds. All that in my relatively small room, and, of course, many showcases with butterflies, also other insects. I had a rifle and went often on excursions and shot small birds, which my man then stuffed for me. Some big birds I also hung on the walls in other rooms.

Very often I went on bigger excursions with other boys, after we had formed a club. Once I went with a friend on an excursion for about two weeks. His name was Horowitz and he later became a doctor too. We went on foot to the North to the border of Galicia to a bigger city, Wiznitz, where the Czeremosz river joined the Pruth river, crossed over a bridge to Kuty in Galicia, and then walked along the Czeremosz river. There the Carpathian Mountains started, beautiful woods, I remember some names of villages which we had passed: Rostoki, Hryniawa, Holoszyna, and Jalowiczora. We used to stay overnight in peasants houses. We had very little money, but we did not have to pay anything for staying overnight, and we ate very little. We had planned to walk to Koresmezo, a pass on the Hungarian border. But my friend found Hryniawa very nice, and did not want to go any further. So, we broke up, and I continued alone. I knew later that he was right and I very wrong. I went alone deeper and deeper into the mountains. In Jalowiczora, I had to stay overnight, since it started to get dark. I happened to come into a Jewish home. The family had just supper, and I was asked to join them at the table. It was my first good meal after a long time. These were extremely nice people. For the night they gave me a fine clean bed with a down blanket. In the morning, I got a good breakfast, I asked them, what I owed them, but they would not accept any money. There was a very high mountain in that area, the Maximec, and I told them that I would like to go up there. There happened to come a man along, who knew the way and had to go up to an alpine farm there. So, I joined him, and it took a long time and much walking and climbing, till we reached the top. There were great many cows grazing there. I had thought that this man would go down with me also, but no, he had to stay there. Now I was in a dilemma, since I did not know the way. I was worried that I could be attacked by a bear on my way, when I walked alone. But there was no way out, and I had to go alone. This man showed me only the direction with the hand and that was all. When I reached the tree area, I soon felt myself lost and did not know where to go. I came to a little brook and had to follow it, but was not sure where it would lead me. I had to jump in the brook from one stone to the next one, for long stretches. Then there were grassy lanes, where I could walk next to the brook. After hours, I finally came into the valley, and yes, it was the Gzeremosz river. I stayed again in the house of a peasant, slept on straw, next to the stable. Early in the morning, without anything in my stomach, I went to the river. There were big floats passing by. I had seen them often before, but I never was on one. I decided to take a journey on such a float. I went to a big rock, which was a little more protruding over the edge of the river and gave signs to an oncoming float. The man in front brought the float really close to the rock, on which I was standing, and I could make a jump and landed well on the float. It was an enormous float, consisting of three floats which were tied together. The second man on that float rammed a piece of wood vertically into one of the big logs, so that I had something to hold on to. It was a terrible journey. The two men had spikes on their shoes, and could relatively easily walk over the logs, but I had regular shoes and since the logs got wet all the time, I had to be careful not to slip. The men warned me not to get a foot between the logs, since I could easily lose it. The logs were about 15 yards long and tied together at the ends, about 15 or 20 logs next to each other, and behind the first float, tied to it, was the second, and behind that one the third float. The man in front had a long rudder in the water, tied to the center of the float on a vertical piece of wood, so that he could move it to the right or to the left, wherever it was necessary to steer it. He had to keep in the middle of the river and to avoid big rocks, which were in the river. The second man was in the back of the third float, and had a similar rudder to handle, and had to keep the float in line with the other two floats. I was wet up to the waist all the time from the splashing water. Especially in the beginning, when the river was not very wide, and very rough, there were dangerous spots, where the float had to pass over rocks, and the logs were spreading apart and going deeper into the water. These were terrible moments. But later, when the river got wider, the ride was smoother and less dangerous. It was late in the afternoon, and it started to get dark, when the float came to the city of Wiznitz, where there were great many floats, and finally came to a halt. Walking and jumping over many floats, which were there, I finally could reach firm ground under my feet.

I had not had anything in my mouth all day, not even a drink of water. I found a little hotel in the city and fell into the bed. I had to pay the next day two crowns, and that was almost the end of my capital. There was a bus going to the town of Berhomet, which was, as I knew, in the Seret valley, and not very far was the city of Storozynetz, where my uncle, Dr. Isidor Drancz and his family lived. I took that bus to Berhomet, and there, with my last money, the bus to Storozynetz. They were glad to see me, and there were Aunt Gusta, my cousin Isabella, of the same age as I, whom I had always loved very much, and my cousin Egon, who worked as a dentist in my uncle’s office. He had a congenital heart disease, and later a so-called cor bovinum, which means an enormously enlarged heart, and he died at a relatively young age. I remember that my aunt had found in my backpack a hard-boiled egg, which was smelling terribly. It was part of the food which my mother had given me when I had started my excursion. It was, in spite of all the hardships, a beautiful experience.

I did not mention yet that Czernowitz also had a beautiful theatre, the Stadttheater, which had been built around the year 1900 and was almost a replica of the Deutsches Volkstheater in Vienna, built by the same architect. All types of plays were offered: operas, operettas, dramas, classical as well as modern, comedies. A large ensemble of singers and actors was brought every year from big reservoirs of Germany and Austria, and great works of art were performed. The repertoire was enormous and diversified, greatly satisfying an always enthusiastic audience, which filled the house to capacity. Not all of them, but a great many were excellent actors and singers. There were no limits in the repertoire: operas by Meyerbeer, Donizetti, Halevy, Rossini, Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, Weber, Leoncavallo’s Il Pagliaccio, Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, always played together, Bizet’s Carmen, etc., of course not all played in one season, but over the years. We saw great many classical works, by Shakespeare, and many of the great German playwrights, and also modern ones and many comedies. A big role played the operettas, which were very popular, from Jaques Offenbach and Johann Strauss down to Milloecker, Leo Fall, Franz Lehar, Oscar Strauss, and you could hear always people in the street singing or whistling melodies of these operettas.

The first play I saw in that theatre at the age of about 13 years was Hamlet and I felt very bad that I could not see from my seat in a box—we called it “Loge”— in the uppermost circle the ghost of Hamlet’s father, and only hear it. The first opera I heard was the Flying Dutchman by Richard Wagner. Later, I became a theatre fanatic and hardly missed any performance. I played many melodies of the operas and operettas on the piano, in my way and mostly from memory.

Here I should also mention that Czernowitz had also a concert hall, called the Musikvereinsgebäude, and a music, conservatory. Many great pianists, violinists, and singers came to give concerts. I remember to have heard among others: Rachmaninoff, Arthur Schnabel, Artur Rubinstein, Jan Paderewski, Wilhelm Backhaus, Fritz Kreisler, and the great Belgian violinist Ysaÿe. In later years I hardly missed any of the concerts of the great artists, who came to our town. I should mention here that the old theatre, abandoned, after the new one was built, was still standing, just diagonally across our home in the Türkengasse. There was a large empty area in front of that building, which we children used as a playground. The abandoned theatre had still the rows of seats, mostly broken and vandalized, and the stage. In the back of the building lived a mister Falikmann with his family and he was supposed to keep order in the old house. But we children were allowed to go in and to play there. There was still the swan, which was once used for performances of Lohengrin, there were all kinds of spears and swords, great many stage-wings etc., everything dusty and in bad condition.

Czernowitz can be called a provincial town, but it was not a backward town , since it had a high percentage of intelligentsia. It was a clean town. The schools were very good, and what we learned in the gymnasium was the same that was learned in the other cities in the West, in Vienna and other big cities. Greek is not being taught in the United States in high schools, and Latin only for one or two years. These are important languages for general education. We learned Latin for 8 years and Greek for 6 years. German literature played the most important role in our education. All the great classics from Goethe and Schiller down were studied, and it would not make any sense to name them all. Their names are not known here anyway, except by people who make a special effort to study German in college and at the University. Heinrich Heine is generally quite well known, but names like Leasing, Wieland, Koerner, Rueckert, Hebbel, Chamisso, Lenau, Scheffel, to name just a few, are more or less unknown, but played an important part in German countries and in our lives. We read their works in school, either plays or poems or novels quite in detail, had to know many poems by heart, recite them, and saw many of their plays in the theatre. Some of the modern German authors like Thomas Mann and Gerhart Hauptmann are quite well-known here. I have mentioned all that to show that we received a well-rounded education in our schools.

You hear so often people say that Latin and Greek are dead languages, and that it is wasted time to learn that in school. That is so wrong. We did not learn it to speak these languages. We learned it in order to be able to read and translate important works written by great Greek and Roman writers, and to learn ancient history and philosophy. This is of enormous importance. Is it not important to know about Greek mythology, to know the details of the Trojan War? That is why we read Homer’s Iliad and the Odyssey, and some of the tragedies of the great writers Euripides, Aeschylos, and Sophocles, which enriched enormously our young lives. We learned thus about Oedipos, Elektra, Iphigenia, Theseus, Herakles, Perikles, Demosthenes, Pythagoras, Solon, Plato, Socrates, Archimedes, Aristotel, Alexander the Great, etc. The list could be continued, but I better stop. These were important people and that is why we learned Greek, to learn the details about them.

And the same applies to Latin. We learned history, spanning more than 1,000 years, from the foundation of Rome to the middle of the first millennium, about the expansion of the Roman Empire, the great men who became leaders, Julius Caesar, Pompeius, Augustus, Nero, Titus, Constantin the Great, etc. I only mention a few names, the list is almost endless. I should mention a few great Roman writers, Livius, Virgil, Cicero, Sallust, Seneca, from whom we learned so much about Roman history, the expansion and the fall of the Roman Empire. That is why we learned Latin. Not to speak it fluently in conversation, but solely to learn history and philosophy as a foundation of our modern world. There is so much more that we did not learn, and which had to be left for later times. There was so much more going on for thousands of years in other parts of the world in China, India, Africa, and America. But with Greek and Latin we learned a lot, and that is what I want to say.

I want to describe here many other activities in which I engaged during my adolescent years. There was, for instance football, what we call here soccer. There were many football clubs in Czernowitz, but it was quite difficult to get admitted into one, as it required intensive training. So, I and a number of colleagues of mine decided to form our own football club. We called it the “Holland Club,” Why just Holland, I could not explain when asked. So, we went out on the Horecza meadow, where all the other clubs played, and started training. But since the other clubs, which were already in existence, declined to play against us, as we did not belong to any league, we formed ourselves teams and played against each other. This lasted for a while, but not for long. The whole thing soon fell asleep, and other things became more important.

I also liked to play billiards. It was a different kind of billiards than the one usually played here. Here the table has 6 holes, into which the ball fell in, and it is being played with a great number of balls. We played on a plain table without any holes, and only with 3 balls. The ball, which one hit, had to hi the other two balls, and you continued as long as you hit the other two balls. Only when you missed the second ball, the other player took over. Each successful hit was being counted. Tie game was called Carambole. I brought it to some mastery in billiards. But it required going late in the evening to a coffeehouse, which had a billiard room, and that was not so good. There was one young man, who asked me almost every evening to go with him and play billiard. That meant often playing for hours and going late to bed. My mother did not like it, but could not do much about it. That was in the years 1913 and 1914.

In these years, I was also involved in training for saber dueling. There were student organizations at all major Universities, grouped with regard to different nationalities, and also religions. The students wore caps in different colors, also bands diagonally across the chest in different colors. There were German clubs, and one of their clubs was the Teutonia, another one the Franconia. There were Polish, Ukrainian, Rumanian, and Jewish clubs. One Jewish club was the Hebronia, others had the names Zephira, Maccabea, Hasmonea. They were promenading on Sundays in the center of the city, on the Ringplatz and in the Herrengasse. Very often conflicts arose, which led to duels between students of different clubs.

At the duels sabers with sharp edges were used. Each duelist had one man at his side, a secundant, who protected him with a saber from dangerous hits. The fighting was with bare chests, but the neck was protected with a heavy bandage up to the chin. The duel came to an end when one of the duelists was injured. There was always a doctor present. It was usually a cut on the face. In those days, people who had scars on their face used to be proud, since they had the proof that they were courageous and had risked an injury. Some people had many such scars on their face.

These student clubs had so-called pro-fuchsias, which meant clubs of students in the last years of the gymnasium, before they entered the University. I belonged to such a pro-fuchsia. There lived in our house a student, who belonged to a Ukrainian student club, called Zaporoze. In spite of the fact that I was Jewish, he took me in into the pro-fuchsia of his club, and I underwent a rigorous training in dueling. It required holding the saber high up for up to half an hour and longer, and hitting the opponent, protected by a so-called Stierkopf (bull head), which was a kind of helmet, sitting on the shoulders, preventing any injuries. These young people in the pro-fuchsias were also admitted to student’s beer evenings, which meant drinking enormous amounts of beer and singing student songs, and also meant coming home totally drunk. I participated quite often, and remember it with horror.

Some evenings we went out for serenades. It meant going late in the evening to a window and sometimes into hallways of houses to sing beautiful songs, to please one of the participants, who had somewhere a girl, for whom we serenaded. It usually ended with the girl and her mother appearing in the door or at a window and thanking for the serenade. They did it also a few times for a girl, whom I knew or “liked”.

It is time that I also say something about my musical education. As a young boy of 8 or 9, I had as a teacher an old lady, miss Tomowicz, who came twice a week to our house. She was quite good and I progressed nicely. I practiced much and advanced from Clementi and Czerny to Kuhlau, Diabelli, and Mozart. I had her as a teacher for about 3 or 4 years. I 1iked the piano, and learned many things myself. After a pause, when I had no teacher, I decided to start again with a fine teacher at the conservatory. But I got only 15 minutes or perhaps half an hour once a week with that teacher, who was a great pianist and often was the accompanist of great violinists or cellists who came to our town for concerts. He was very strict and you had to practice and prepare yourself well before each lesson. I had him as a teacher for only one year or perhaps a year and a half, till the First World War broke out in 1914.

I had come quite far by than, could play Strauss waltzes and some Chopin mazurkas, lighter pieces by Mozart and Beethoven, and I learnt myself operetta music by heart, which was very popular then, the Merry Widow, Rastelbinder, Dream Waltz, etc., and some opera arias. I often played for young people, who were dancing. That was always my job, and it meant often sitting for hours and playing for them waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, gavottes, fox trots, and tangos.

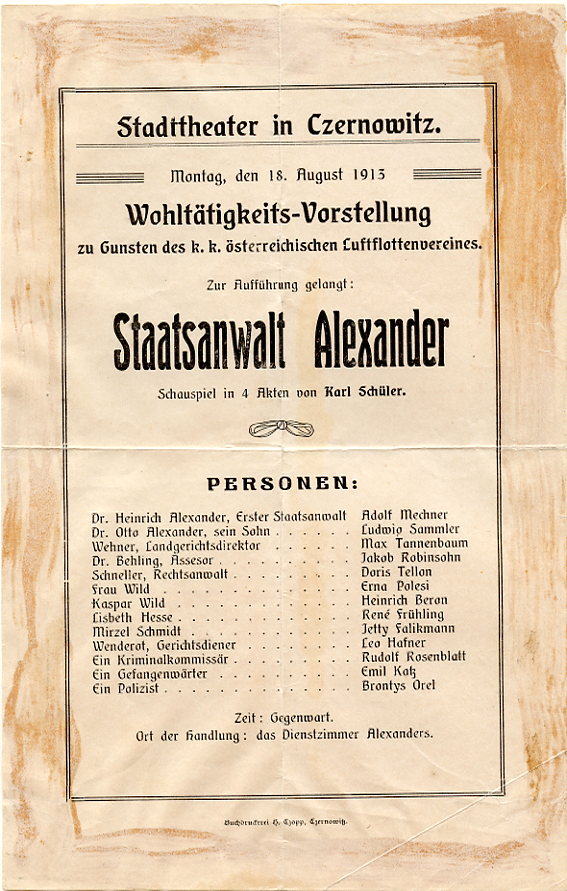

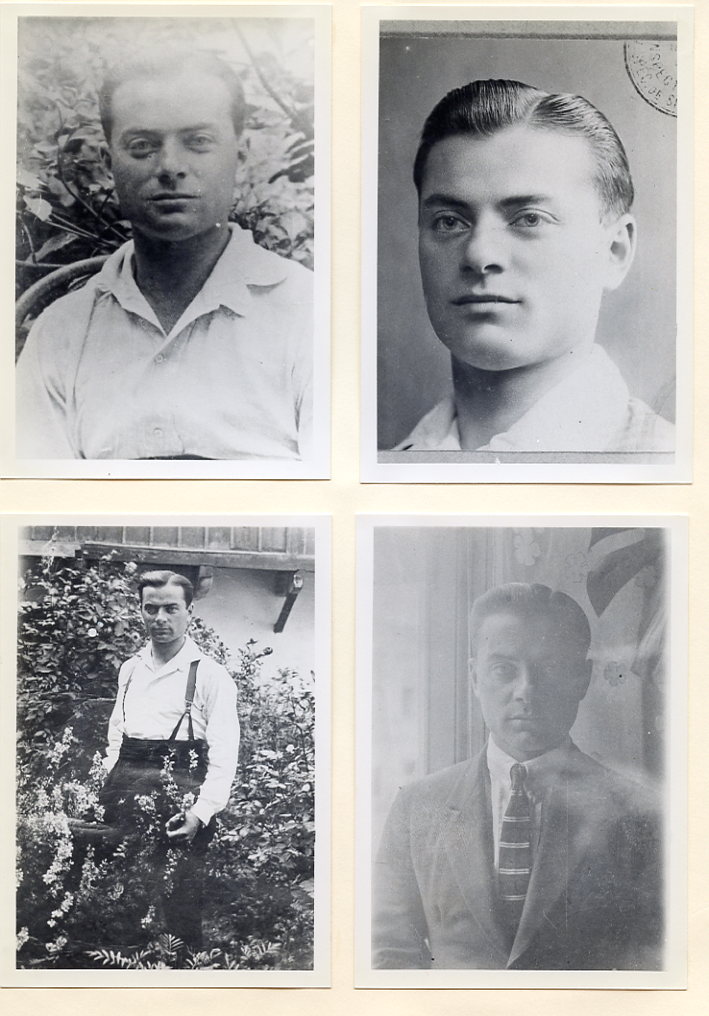

Till now, I had mentioned many hobbies and activities during my younger years. Now, as I advanced in years and became an adolescent of 16 or 17 years, ray interests had changed, though some of the earlier ones remained. I became now interested in theatre playing, and I joined a group of other young people, who had the same interests. We formed a dilettante club, or, as we would say here, an amateur club. We had, as I mentioned before already, a good theatre in Czernowitz, but it was closed during the summer months, and that gave us a chance to play in that theatre, also in other smaller towns. Preparations required much work. We gathered for rehearsals usually twice a week in the evening, and it took many months, till we finally came out on the stage. I still have printed theatre programs, which show that we played for instance on the 18th of August, 1913 a play: Staatsanwalt Alexander (district attorney Alexander), a tragedy in four acts by Karl Schueler. I played the title role.

By the way, the 18th of August was the birthday of our emperor Franz Josef I, a big holiday in those days. As a young fellow of 16 years, I had to use much restraint to play the part of a district attorney who had a grown-up son. But I was told that my performance was very good, and that encouraged me. In the same year we came out with two more plays: “Hinter Mauern” (Behind Walls), by a Danish playwright Henry Nathanson, which we played in a small town, Novosielitza, near the Russian border. The reason that we played it there was that some of my gymnasium colleagues came from that town, and one of them, Bruno Beron, played an important part in it.

Something very funny happened during the performance, which given in a large hall, filled to capacity, so that the first row of seats was close to the stage. Many difficulties arose during the performance, but the audience showed much understanding and accepted everything as it was. I had two roles in that play: In the first, second and fourth act, I played the role of a doctor, and had a small black mustache. But in the third act, I played the role of an elderly man with large gray sideburns. My mustache in the first two acts was well pasted on with a kind of rubbery glue. But after the second act, I had to remove it, and that could only be done with Vaseline. After the third act, I had to remove my sideburns, and put the black mustache back on, since I was now again the young doctor. But unfortunately, I had not removed thoroughly the Vaseline from the left side of my upper lip. Therefore, the glue did not stick well, and while I was on the stage, the mustache from the left side fell off. I noticed it right away and decided to leave things as they were, but to show the audience only the right side of my face, and not to turn my head. That would have been perfect, especially since the play was very close to the end. But I had to have a conversation with my younger brother in that play, a part which was played by my friend Bruno Beron, whom I mentioned before. I looked straight at him, and when he saw that I had only half a mustache, he pulled it off. The audience saw it and roared. I have laughed about it for years, whenever I thought about it, and also now, while I am writing that down, I have to laugh and my eyes are full of tears.

I remember that the next day we made an excursion across the Russian border into Russian Novosielitza with border passes, which we had received. It was more or less a Jewish town and made the impression of a completely different world.

The third play, which we produced in that year, was “Der Strom” (The Stream) by Max Halbe, a tragedy in three acts. We played it in the city Storozynetz, where my uncle Dr. Drancz and aunt lived with their family. I had to go there a few days earlier, since I had to build the stage on a podium, the wings with doors and windows, install the lights, the curtain etc. All that I had to do myself. But it was a good performance and a great success. These were three plays in the year 1913, and for the time being the end of my “career” as an actor, because the next year the First World War began. But I came back alive from the war, and in the year 1919, our club, and with many good actors, became active again. Later more about that.

So far, I have described about all my activities and hobbies of my younger years, but the picture would be incomplete if I would not describe a little more in detail my teachers in school. Some of them were excellent teachers, real experts in their fields, we had in our school a teacher, Dr. Artimowicz, who had once received a ring with a brilliant from emperor Franz Josef I. for outstanding work. For Latin, we had a teacher, Dr. Tumlirz, who had written a textbook, which was used in many schools as a textbook. And for Greek we had a professor Wurzer. He was a heavy built man with a big belly, and the students used to say that he was a drinker. But that was probably not true, and we always saw him alert in school. I remember, when he once described Socrates and told us that he was condemned to die, and that he took the cup with the poison to his lips and drank the poison, he really cried, and tears came down his cheeks. The students made often fun of him, and that induced me to do it too. He wore always eyeglasses, and had them always near the tip of his nose. I once brought a pair of eyeglasses to school, and put them on, the same way he wore them. He looked at me for a moment, but did not say anything. He generally ignored these things, and this way maintained discipline in his class. But I was always [up] for fun, and often played the clown in the class, imitating the way some professors behaved or talked. We had for instance for history a professor Barlion, who could not say well the letter “S.” It always sounded more like a “T.” Instead of “setzen Sie sich,” which means “sit down,” he said “Teten te tich.” But he was a good-natured man, and did not get angry when I spoke to him in a similar way. I did not have great difficulties with him, probably because he knew that I liked history very much.

One of my favored subjects was the German language. We often had to write essays, either in the classroom or as home work. Great poems were analyzed in detail, and we had to learn them, so that we could recite them by heart. I still remember a few poems and can recite them, for instance “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” “The God and the Bejadere,” “The Singer”, all three by Goethe. We had a professor, whom we all loved. We often begged him till he complied to read for us poems by Nikolaus Lenau, which he did in a wonderful way.

Once I had the special task of writing an essay about the theatre in old Greece, how they played at that time, around 400 B.C. in the open air in a kind of amphitheater, with a chorus, and the actors wearing masks. To prepare myself for that task, I went to the library of the university, where I read books about and wrote important details down. The reading of my essay took a whole hour and brought acclaim by the teacher and the colleagues. Other pupils had to do similar work on other subjects.

I also want to mention that early in life, when I was about 16, a colleague of mine, Albert Welt, proposed to me to study English together. We got up very early each morning, at 6 o’clock, and went together to the Volksgarten. We sat each on a separate bench with a book, that gave, of course, the meaning of each word and the pronunciation, and we then sat together and read small sentences together. It was fun, and we did that for quite some time.

Two more interesting things are worth mentioning. I was interested in American history and wanted a complete list of all the presidents. I got one by using the encyclopedia, which we called lexicon. At that time, Taft was president. I looked him up in the lexicon, and found that he was the successor of Theodore Roosevelt. Then I looked up Theodore Roosevelt and found that he was the successor of President McKinley, who was assassinated, and so on, till I had a complete list of all the presidents from George Washington to Taft. And there was one more interesting thing: I always had the feeling that I will get one day to America. That was one of the reasons why I had started to learn the English language. One day, I got an American flag, made of silk, of the size of a handkerchief, and for a long time I wore it, nicely folded up, In the front pocket of my jacket, so that the stars or stripes could be seen. I always said and still say it that I have a sixth sense, foreseeing unforeseeable events.

Before closing the chapter about my younger years, I should say something about my more private, intimate life. I was now 17 years old and a so-called handsome fellow, and I liked girls already for years, and some girls liked me, and I had a few times fallen in love. The one I really loved and for a longer period of time up to the time of the outbreak of the war, was Mitzi Klein, who lived with her parents and one brother in the house next to ours. She was very pretty, slender, and had especially long eye-lashes. I played on the piano in her house, when the young people were dancing. We went often out on walks, also on excursions in groups, but it took a long, long time till we kissed each other. I had a competitor, Raimund Zwirzina, called Mundi, a very handsome fellow, and I often thought to have reasons for jealousy and great unhappiness when I thought that she preferred him. I wrote poems for her, even composed music to these poems. Unhappiness changed to happiness from one day to the next. I always had a revolver in my house, also a rifle. Once my unhappiness was so great that I was very close to committing suicide. But I changed my mind in time. That was the smartest thing I ever did.

There were some wars before during my lifetime: The Russo-Japanese war, February 10, 1904 to September 5, 1905, ending with the victory of Japan, and taking over besides important Russian territories the reign of Korea. Then the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which belonged to Turkey, by Austrian-Hungarian troops on October 6, 1908. This caused great disappointment in Serbia, which had long desired to get these two provinces, and increased the enmity between Serbia and Austria. Then the Tripolitanian war, October 5, 1911, between Italy and Turkey, ending with the annexation of Tripolitania, now called Lybia, by Italy and the treaty of Lausanne, October 18, 1912. Next came the First Balkan War, October 18, 1912, between Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece on one side, and Turkey on the other, each of the three first mentioned intent to grab a part of the European territory of Turkey.

At that time, at the age of 15, I was already very interested in these political events and observed the changes of the map of the Balkan intensely. Montenegro had also joined in the attack. The treaty of London on May 30, 1913, ended this First Balkan War with the loss by Turkey of almost all the European territory. The Bulgarians had advanced to the Chatalja Line, a row of fortifications for the protection of Constantinople, which was then the capital of Turkey. The Bulgarians had been warned by the Russians not to go beyond this line. Constantinople and the Bosporus were too important to the Russians, since they were at the narrow entrance into the Black Sea. But the victors were not satisfied, each of them demanding parts which were given to the others, and so the Second Balkan War started on June 29, 1913, with the attack of Serbia and Greece against Bulgaria. Now Turkey resumed the war and attacked again Bulgaria, and Rumania entered the war as a new participant, attacking Bulgaria from the North.

Bulgaria was rapidly defeated and the war ended on August 10, 1913, with the treaty of Bucharest. Bulgaria was the loser and had to give up some of the occupied territory, a part of Macedonia, but kept a short coastline on the Aegean Sea at Dedeagatch. Rumania gained a part of the Dobrudja near the Black Sea, and there were many re-adjustments of the borders of the other Balkan countries. The Serbs, who had advanced to the Adriatic Sea, were later forced by an ultimatum of Austria to give up that territory. Greece, which had advanced too far North, had to give up a part of that territory by an Austria-Italian demand, and Montenegro was forced to give up Skutari, which it had occupied, and the state of Albania was created, with Tirana as the capital, and Serbia remained landlocked.

After that, there was relative peace in Europe and everything seemed fine. We lived like in a paradise. All the wars described were far away, and we were not touched by them. There were manipulations by the great powers, treaties of friendship, and what have you, and we read about it in the newspapers, visits by the Russian Czar in Berlin, by the King of Italy in Vienna, unrest here, unrest there, exchange of diplomatic notes, ultimatums. But in general, there was peace, probably preoccupation by older people, but we younger people in Czernowitz did not care. For us it was living in paradise: There was only school that required some effort. The sixth year of gymnasium was coming to an end. Else had come home from Vienna with all her paintings and drawings. My stepfather’s business was going very well. The magazines were filled with bottles of mineral water, many thousands of them. There was little Walter, whom I loved very much, and on whom I spent much of my free time. I contributed very much to his education during his first four years. He was a gorgeous child and very intelligent. This may have been the reason that his father liked me very much.