1914

But then, one day, there was a thunderclap. On June 28, 1914, the archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife were assassinated during a visit to Sarajevo in Bosnia by a young Serbian, Gavrilo Princip, a member of a terrorist organization. The Vienna government was convinced of the complicity of Serbia. Franz Ferdinand was the crowned prince since 1889, when the only son of emperor Franz Josef I., crown prince Rudolph, had committed suicide. Since then, for 25 years, crown prince Franz Ferdinand had waited to become emperor, and was when he died at 51 years old. He was not especially popular in Austria, but there was outrage in the world and sympathy for Austria. It was generally believed that a localized settlement would be possible. There were consultations between Germany and Austria, and war against Serbia was considered. But England, France, and Russia also held consultations and concluded that the best way out in that serious situation would be to exert pressure on Austria to negotiate and not to take drastic steps. But an Austrian crown council decided to send an ultimatum to Serbia with many demands, difficult to accept by an autonomous country. One of the conditions of that ultimatum was, that Austrian police should be allowed to enter Serbia and search there for the perpetrators of the assassination and bring them to Austria to court.

Serbia received assurances from Russia that it would declare war on Austria in case that Serbia would be attacked, and Russia had received assurances from France of support. Whatever Austria had done, was, as is generally believed, instigated by Germany. The ultimatum was taken to Berlin, before it was sent to Serbia.

The answer of Serbia to the Austrian ultimatum was vague, and Serbia had ordered mobilization against Austria, and Austria mobilized against Serbia. This was on July 25, 1914, almost a month after the assassination of the crown prince Franz Ferdinand. England proposed a conference by the great powers to settle the whole affair, but Austria and Germany refused. On July 28, Austria declared war on Serbia, and for the next few days, while notes were going forth and back between the great powers, general mobilizations were started, first in Russia, then in Germany, declaration of war by Germany on Russia on August 1, then on France on August 3, followed by the declaration of war by England on Germany on August 4, by Germany on Belgium, by Austria on Russia on August 6. Then followed more declarations of war, by Montenegro on Austria on August 5, by Serbia on Germany on August 6, by Montenegro on Germany on August 8, by France on Austria on August 12, by England on Austria also on August 12, by Japan on Germany on August 23, by Japan on Austria on August 25, by Austria on Belgium on August 28, by Russia on Turkey on November 2, Serbia on Turkey on November 2, England on Turkey on November 5 and also France on Turkey on November 5. Italy, which was bound by the Tripartite Plan, the Triple Alliance, to participate in any war, in which Austria and Germany were involved, broke the agreement and remained neutral, a great disappointment for Austria and Germany. Later on, on May 23, 1915, it entered the war against Austria and Germany. This war could have been avoided, but Germany wanted it and instigated Austria. The old emperor, Franz Josef I, was senile, 84 years old. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II and his chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and the Austrian chancellor, count Berchtold, cooperated and achieved what they wanted. There were the German generals Ludendorf , Palkenhayn, Moltke, who all wanted war. And they got it, the most terrible war.

At the time of the assassination of the crown prince there were big headlines in the newspapers, followed by daily exciting news, when the diplomatic maneuvers started, but still, there was peace, and practically nobody thought that war may result. Especially we young people did not think about it. It was all the time like a thunder far away, lightning far away, but still peace and everything fine as usual. The newspapers brought the news all the time with much optimism, since there were conferences, which could lead to a settlement. We believed that our emperor and emperor Wilhelm II wanted peace and made great efforts to achieve it. This had a calming effect and we felt secure, for a while at least, for a few weeks. That was in July.

But the news and headlines became more and more serious, and then, one day, the storm broke loose, with the Austrian general mobilization on July 31, and the next day by Russia and Germany, and declarations of war. The newspapers told us all the time that our fatherland had been attacked, and that we had to act in self-defense, and we believed all that.

And now, over night, something that nobody expected developed, an enormous enthusiasm for the war. From early in the morning, great masses of people gathered in the center of our city, and everybody felt electrified. The people stood there and sang patriotic songs, young and old alike. The same thing was reported from other cities, from Vienna, Berlin, and Paris. There were some older people who kept silent, who had other ideas about the war, but the masses were there and they shouted and sang, and they appeared to be happy. Very soon, troops began to march, with music bands in front. That went on for two days. But many young people had to run, they had to run to their commandos, to put on their uniforms, and soon the enthusiasm calmed down.

Soon my cousin Marzell Drancz came, dressed in a gray uniform, and he looked great. He had to go to his regiment, and he stayed only a few hours in our home. I kind of envied him. I had already before the idea of entering the army voluntarily, and when I saw him, my enthusiasm for the war grew. Many of my colleagues wanted to do the same. And I really went into a mobilization barracks, but there I was told that I was too young and that I needed the consent of my parents. But my mother refused to give it to me, and I consented that I would wait till I was 18.

Our city, which was near the Russian border, had to count on an invasion by Russian troops, and many families packed and left, most of them for Vienna. The news during the first few weeks was good, there were victories for the Germans on the Russian front, and right in the beginning the Germans invaded Belgium and occupied it within a short time. The Germans also advanced into France to the Marne river. But bad news soon came from the Russian front, where the Russian troops had advanced deep into Galicia. This news were bad for the Bokowina also.

One night, at the end of August, there was an enormous explosion, and soon we found out that the bridge over the river Pruth had been destroyed by the Austrian troops. Everybody started now to run, to grab a few valuables, to pack them into valises, and to run into the streets. We thought that we would still get a train and would leave. But since the main bridge had collapsed, no train came and there was no chance to go to Galicia. Everybody now ran to the other station, station Volksgarten, hoping to get a train to the south of the Bukowina and to Rumania. But no train came there either and after many hours of waiting, we went back home. My brother-in-law, Paul Rosegg, states that he remembers having seen me at the station Volksgarten that night, standing there with a valise, wearing a derby hat, which we called in German Steifhut (stiff hat).

For the next two or three days we heard rifle fire, and many people went to certain high areas in parks and observed movements of our troops in the fields. It did not take long and the Russian troops entered the city on September 15. They were under the command of general Evreimow, and they entered with very little shooting. I saw the general, who had a little white beard, and seemed to be a rather old man. He had an easy job taking Czernowitz, since the Austrian troops had retreated into the Carpathian mountains.

There followed days of great depression. The Russian troops were well disciplined. But the general demanded a large contribution of money, and since most of the rich people had left the city and the banks had been evacuated, before the Russians came, there was not much money, and therefore the general demanded that all the people should bring their silver and jewelry within two days to a certain place, a large office building. That was done and the people got receipts. This he demanded as assurance, that the Russian troops would not be harmed by anybody. A few days later, to show his magnanimity, everybody could take the things, they had handed over, back with their receipts. There were very few incidents, where Russian soldiers had entered stores and demanded merchandise. Some of them were apprehended by their officers, and first of all whipped with a whip, which every officer carried, and then arrested. In general, we had a bad time, and reason to worry. The schools were closed, and there were, of course, no newspapers. On account of that there were all kinds of rumors about events in the war, about victories of the Austrian and German troops, and also about reverses. My enthusiasm for the war had abated since a long time, and especially since the invasion of the Bukowina by the Russians.

But after a defeat in Galicia, the Russians retreated, and had to pull the front back, and in November Lemberg and Czernowitz were free again.

Flight to Vienna

We still heard from far away cannon fire, especially at night, and we knew that we were still in danger, and that we would have to leave our home. This was very difficult to accomplish, since the way to the north through Galicia was interrupted. There remained only the railway to the south to the border of Rumania, which at that time still was a neutral country. We had to plan what to do, and I remember that Else was in the center and had a leading part in the conversations, and the planning. We had relatives in the city Suezawa, which was near the border of Rumania, and it was decided to visit them there, and to try to go from there through Rumania to Vienna. We packed in a hurry took the most necessary things along and left, but in the excitement left a large cassette with silver table ware on the table. We gave the key to the apartment to one of our neighbors. My stepfather had left long before, had entered the army, since he was a relatively young man, about 36 years old.

Anyway, we all left for Suezawa, and stayed for about two days in the home of our relatives. We learned there that only women and children could leave the country, but not males, who were liable for military service in the Austrian army. We probably knew it already before, and had planned what we would do. I said goodbye to my mother, Else, and little Walter, who took the train through Rumania, whereas I was put in a horse-drawn carriage, which took a very long road toward the Carpathian mountains, through the cities Gurahumora, Kimpolung, and Dorna-Watra. There I succeeded, by paying some money, in being put on a military truck and, hidden under straw, to go through the Carpathian Mountains, and after passing the border control undiscovered, to get Into Hungary and to the first railway station Borgo-Prund. Prom there it was easy to get a train, which took me the long way through Hungary to Vienna. This was the first time that I had become a refugee. (My brother Carl tells me now in a letter that he went exactly the same way from Suczawa to Vienna, probably a day before or a day after me.)

For now, we were all together in Vienna, and stayed for a few days in the home of my aunt Rosa, which was in the 8th district in the Schloesselgasse. It was at about the end of November, when we had arrived there. My mother, Else, and Walter had arrived about two days earlier, and went immediately to look for an apartment. They found one in the 4th district in the Margarethen Strasse No. 50, a small apartment for my mother and Walter, and another room, one flight up in the same house, for Else. I got an invitation from aunt Rosa to stay in her apartment, which I, of course, accepted.

Vienna made an enormous impression on me. I found it beautiful, especially the inner city, the 1st district, which was surrounded by the Ringstrasse with its beautiful buildings. I had lived all my life in Czernowitz, which was a small town, and Vienna was an enormous city, and now everything was so different. I soon found out that most of the professors from the gymnasium in Czernowitz had also emigrated to Vienna, and that school had started a few weeks before. I registered right away for the seventh grade.

The school was the Sophiengymnasium in the 2nd district in the Circusgasse. In the morning, the Viennese students had their classes, and we refugees from Czernowitz had the classes in the afternoon, so-called parallel classes. Getting there from the 8th district by streetcar took quite some time, but I attended the school regularly. Carl got soon an engagement with the theatre in Posen in Germany as operetta tenor for a whole season, where he was very successful.

My aunt Gusta and her daughter Isabella had also come from their hometown Storozynetz in the Bukowina, and they found an apartment in the 4th district near my mother. Her husband, uncle Isidor, who was a physician, had probably stayed behind in Storozynetz, or perhaps joined them later. I don’t remember to have seen him in Vienna. Neither did I see my stepfather there, while I was in Vienna.

A completely different life had begun for me, and it was not easy to adjust. I lived now in the home of my aunt Rosa. It was a nice apartment on the second floor, consisting of two bedrooms, a living room between them, and a very large entrance hall, which was also the dining room, and next to it the kitchen. In one bedroom aunt Rose and uncle Emmerich, called Imre, were sleeping, in the living room the two boys, Herbert and Felix, and the third room was shared by my cousin Alice and me. There was a maid, who slept in the kitchen. It was a peculiar situation, but nobody ever found anything peculiar about it. After all, I was only a young boy, 17 ½ years old, and cousin Alice was already 19. She was extremely beautiful, tall, with long, blond hair, and, of course, I fell in love with her and she with me. But nobody noticed it, or at least seemed to notice it, as we knew how to conceal it in the presence of others. Aunt Rosa, I am sure, knew it, and she had planned it this way, and as a good mother, wanted her daughter to have a good time. When everybody went to bed at night, we two went into our room and closed the door. We were never disturbed, it never happened that anybody came into our room at night. We started the night by reading. I had a philosophical book, which I read to her every evening, Sex and Character by Otto Weininger, a very famous book in those days. But I was not very successful, trying to explain complicated statements and ideas to her, and it was to no avail. But I continued reading every evening one or two chapters to her, till we got sleepy. I can say, that these were very happy times in my life. This went on for about half a year.

This was one part of my life in my aunt’s home. But my life there was filled out with many other activities. There was Emmerich Hartman, called uncle Imre, whom I had already mentioned before, whom my aunt had married around the year 1910, after my grandfather had died, and after she divorced her first husband in Berlin. I had also mentioned that uncle Imre became blind and had developed all the serious symptoms of tabes dorsalis. It was a tragedy. He was a tall, still very good-looking man, with a blond mustache, but quite helpless. He was unsteady on his feet, but could walk in the house without help, holding on to the furniture. At the table he needed help, as the meat had to be cut for him. His right hand was not well under his control. For Instance, when going down the stairs and holding onto the banister with his right hand, it often happened that the hand went up into the air, and he lost the grip of the banister. But I was leading him, when walking with him, and, as far as I remember, he never fell. I went very often out on walks with him. I liked him very much, and he liked me too, I am sure. I spent much time with him, from morning till noontime, when I had to leave for school. I had to read to him the newspaper, The Neue Freie Presse. He was very interested in the news of the war, and so was I.

During the two months, when we had the Russians in Czernowitz, we did not know what was going on on the war fronts. But after they left, we heard the news that in the meantime the Germans had occupied almost all of Belgium and had advanced in France to the river Marne, but had been stopped there, almost miraculously, by the French and English troops. They never advanced to any degree beyond that line during the rest of the war.

But on the eastern front it was a different story, as the Russians had advanced deep into Galicia, but further north the Germans under General Hindenburg had won a great victory over the Russians at Tannenberg. On the Serbian front in the south, the Austrians advanced slowly and it took some time, till they occupied Belgrad. This was the situation, when I started to read regularly every day the newspaper to uncle Imre.

He was an enormously cultured and knowledgeable man in many fields. I had to read to him many books, which interested him. Among the most important I remember a book by the great zoologist and paleontologist Guvier, who lived from 1769 to 1832, who was the founder of the sciences of comparative anatomy and paleontology. Then I remember to have read a book about the island Atlantis, in which the author tried to prove that it really existed once, and formed a land bridge between Europe and America. This is still believed by many. It was a large, really interesting book. Then I read to him a book about historic places in Vienna and each time, when we finished a chapter, we went out to the place we had read about. These were places, where once walls were, rests of the walls which surrounded Vienna, when the Turks besieged the city in 1529. There was later again a siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1683. He knew exactly where to take me, and I learned how to walk with him. Each time we had to cross a street, I pressed his arm and he knew that he had to step down from the sidewalk, and then I pressed again his arm, and he knew that he had to step up onto the sidewalk. These were long and most interesting walks.

Sometimes there were difficulties, when he had to go to a toilet. Vienna had many public toilets, but when we were not near such a place, we were in a dilemma, no matter how fast we walked. He had no control over his bowels, the poor man. He never accepted my help, and I had to wait outside, and somehow he cleaned himself and we went home, where he had to change cloths. But in general, I had much pleasure with him, and I learned a lot on account of the wonderful books I read to him. He also liked it very much, when I played on the piano for him, especially Hungarian melodies. Once a week, a young lady came, and they studied together old French, as it was spoken about 1,000 years ago. By the way, in the gymnasium, we also learned German as it was spoken in the Middle Ages. Uncle Imre, (the Hungarian name for Emmerich) was born In Slovakia, which belonged to Hungary, but was of German descent. He was always sitting in an armchair, often suffering from terrible so-called lancinating pains, which went through his whole body like lightning, especially on days when the weather was changing. His memory was not affected and neither was his speech. His gait was peculiar and typical for tabes dorsalis: he threw his legs too far forward, before the foot reached the ground again. When I walked with him, he could walk quite fast.

I went often with cousin Alice to the theatre. The Burg theatre was very near, within walking distance, also the Deutsches Volkstheater, and we saw many beautiful shows, classical and modern ones, and sometimes we also went to the opera. We sat, of course, high up in the gallery. I often visited my mother in the Margarethenstrasse, went there usually on foot, which took me almost an hour, and my mother sometimes came to visit us, which was not difficult by streetcar.

Else was then already engaged, her fiancée, whose name was Franz Lang, was a student of architecture. He later got a job with the Department of Architecture. I liked him very much. He was good looking and a very fine gentleman. He lived with his parents in the same house, where my mother and Else lived, on the ground floor. He had a sister Mitzi, extremely beautiful. Later, when I was in the army, Else and Franzi got married. But the marriage did not last long, only about two years. They had a nice artists studio in the Wiedener Hauptstrasse in the 4th district, where Else did some painting, while he went to work.

In the meantime, the war expanded more and more, since Turkey had entered the war on the side of the central powers, Austria and Germany, and Japan on the side of the allies, England, France, and Russia. Germany had many colonies in Africa and Asia, and there also war fronts opened. On the high seas there were sea battles and many large ships were sunk. Australia and New Zealand had also sent troop contingents to the war fronts. On the Russian front the Russians had succeeded in taking the fortress of Przemysl in Galicia, and had penetrated the Carpathian Mountains and occupied a small area in Hungary. In Galicia they had advanced to Krakow. But an Austrian-German offensive at Gorlice was successful and the Russians retreated, Przemysl was retaken, also Lemberg. This is only a short outline of the happenings in the war in the first few months. It would take much more effort and time to describe many details. But this I will not do. After all, this is a biography of our family and I have to concentrate on that. Some details of the war will have to be mentioned, as far as they affected us personally. It was a terrible, bloody war with loss of life of millions of people, lasting over 4 years.

I have advanced in the description of events regarding our family to the middle of the year 1915. Things had gotten quite bad. There was already scarcity of food, and bread and meat were rationed, also gasoline. But my life up to that time was relatively pleasant, it was nice in the home of aunt Rosa, especially on account of Alice and uncle Imre.

All that ended suddenly, when the fiancée of Alice arrived from Rumania. His name was Samuil Patras, and he was of Rumanian nationality. He had studied dentistry and apparently had finished his studies in Bucharest. I was quite disappointed when I saw him and spoke with him. He was a very primitive man, heavy built, and quite uneducated, a real peasant. How Alice could have chosen him was difficult for me to understand. I did not see much love between them, nor real affection. He often lifted her up and carried her around, to show his strength. I was quite unhappy.

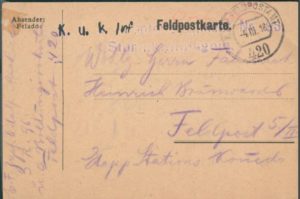

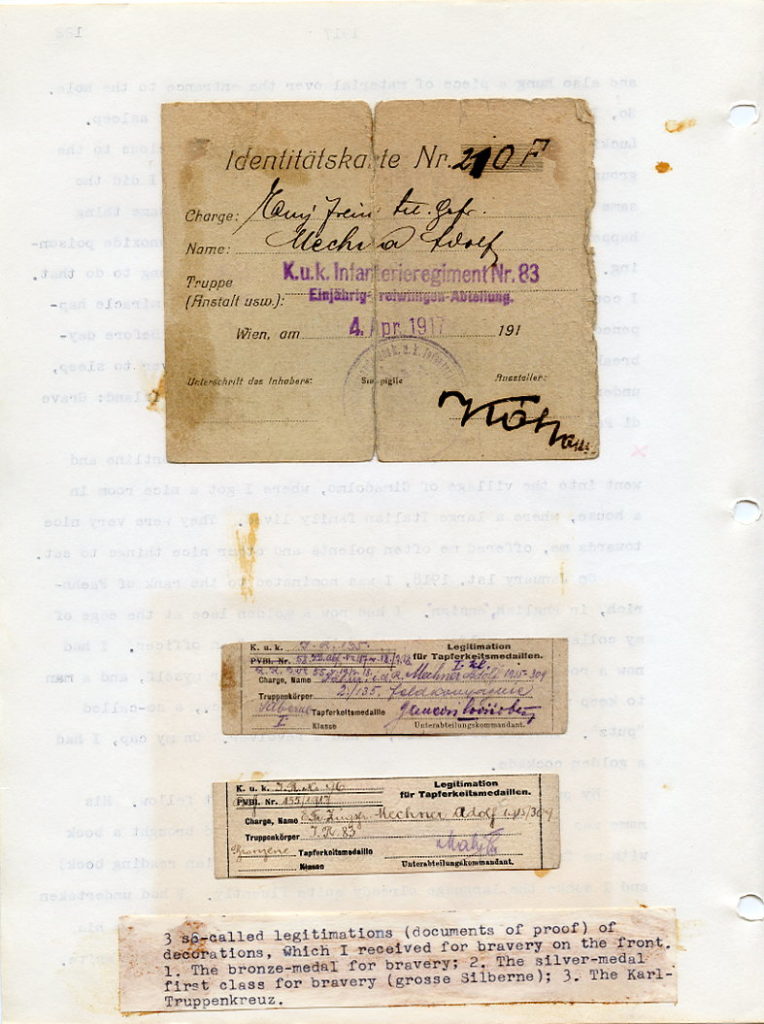

Anyway, I had to leave and moved to the apartment of my mother. I lost much when I left the home of aunt Rosa, I lost Alice and uncle Imre. School also ended soon, and I advanced to the eighth grade. Since I was already over 18 years old, I had to enlist in the army, and the day for entering the army was fixed: It was the 15th of October, 19l5, and I was happy that I was accepted in the Infanterie Regiment No.83 which was stationed in Vienna in the 21st district, as a so-called Einjaehrig-Preiwilliger on account of my college education, which implied that I would later be sent to an officers school and become an officer.

There was still the long summer before us, and now my mother had and aunt Gusta had planned something very special: Aunt Gusta wanted for some reason to travel back to Storozynetz in the Bukowina, and I should accompany her, and I should go to Czernowitz to pick up the cassette with silverware, which we had left there and some other valuable things. What reason aunt Gusta had to go there, I don’t know anymore. Perhaps uncle Isidor was there and she wanted to join him. The train connection through Galicia was free since the retreat of the Russian army. So, one day, we left and it was a long journey. Normally, it would have taken one day only, but we were about three days on the road. There were long delays in smaller, war-torn cities, and I remember that we had to stay in a small town, Kolomea, about half a day. We stayed in a Jewish house near the railway station, where we could get only some bread and milk. There was a very small child lying in a crib and sleeping, and the face of the child was covered with flies, which we constantly chased away, but they were back on the child’s face the next moment. It was hopeless. I remember that the train had to go over the river Pruth over the bridge, which was destroyed by our troops the year before. It was now a wooden bridge and the train moved very slowly and noisily over that bridge.

I got out in Czernowitz and aunt Gusta continued her ride to Storozynetz. I found our apartment in relatively good condition, and the maid of our neighbors was there, and gave me the keys and the cassette with the silverware, which she had found on the table and taken to her apartment to hide it.

The city had changed very much since we had left. There was little life, since many people had left and only the poor people had stayed. The University was reopened, also some other schools, and the City Hall and other institutions functioned again. Many stores had opened again, mainly food stores. At night, the thunder of the cannons could be heard, and people feared a new Russian invasion. That happened later in 1916.

I was supposed to return to Vienna soon. But I met some friends and there were many pretty girls around, and I had the home for myself and so I delayed my departure. I had a real good time there. Then there came a letter from my mother, urging me to return. So, I packed and left, the same way I had come, over the wooden bridge over the river Pruth, and the long way through Galicia and Moravia to Vienna.

All the refugees from Galicia and the Bukowina were supported by the government, and so were my mother and Walter too. Every two weeks, she had to travel to the 2nd district to receive an amount of money, and later, when I lived with her, the amount was increased. This was of great importance, as we did not have anything to live on, since we had lost everything when we emigrated. We had abandoned in Czernowitz the storerooms, filled to capacity with merchandise. Therefore, little cash was available which we could take along, just enough for fares and expenses in the beginning. That is why the support by the refugee committee was of such importance to us. It was probably not much, what my mother received, and I assume that my stepfather, who was in the army, sent her regularly a part of his salary. She had to economise, the poor soul, but I don’t remember that I ever heard her complain. She was always nicely dressed, and prepared nice meals. Once Carl came back, after the theatre season in Posen had ended. Since my mothers apartment was too small, we rented a room around the corner in a house in the Kettenbrueckengasse No. 6, which had a plaque outside that said, that Franz Schubert had once lived in that house. Schubert had also died in that house.

The people who rented the room to us were a couple in the 60th, very nice to us. The man played in the orchestra of the opera house, I think the flute, and his wife was an usher there. Once our sister Else had to stay with us over night. I don’t remember anymore for what reason, and we had no chance to talk to our landlords about it. When they saw her in the morning, they were furious, as they thought that we had taken a girl for pleasure into our room. We had to convince them that she was our sister, and then everything was alright again.

Training

The time came closer for our enlisting in the army, and we had to prepare ourselves for it. Carl had to enlist and leave earlier than I, and he had to travel to Kielce in the occupied part or Poland, where he enlisted in the Infantry Regiment No. 6. On account of his studies in the Akademie fuer Musik und darstellende Kunst he was accepted as Einjaehrig-Freiwilliger, and was later sent to the officers school in Troppau in Silesia, from which he returned as a Korporal to Kielce, and was soon sent to the Russian front near Kirlibaba in the Carpathian Mountains. That much about him for the time being.

My first day as a soldier was the 15th of October, 1915. I had to be at a certain hour there in the morning, and we soon received our uniforms. It was not easy to get the right size of blouse, pants, and shoes. Our civilian cloths we had to pack and put away. Later, we took them home. Many of us were young fellows from Vienna, but there were many boys from Hungary. The Infanterie Regiment No.83, with dark brown collars, was a Hungarian regiment, stationed in Szombathely in Hungary near the Austrian border, but one company was stationed in Vienna. Soon we were in the midst of people, who spoke only Hungarian.

I and many other Viennese boys received the permission to live outside the barracks in private rooms. But for the first 14 days we were not allowed to go outside, since we had to get first basic instructions, in the first place how to salute others, who had already stars on their collars, and officers. We had received uniforms, which were very special and beautiful, especially the pants. They were blue and quite tight, so that the shape of the thighs and lower legs were exposed, and the lower ends of the pants were in the shoes. The upper parts of the pants above the knees had as an ornament a yellow cord. It was a complicated design, with many loops and looked quite good.

The drill started the next morning and was very rigorous. The commando language was German and that was good. We had to learn to stand straight and the command was “Habt acht” and meant not only standing straight, but also to pull the shoulders backward, and to push the chest out, to keep the hands on the sides of the thighs, with the fingers close together, to keep the heels tight together and the feet on an angle separated. Saluting had to be done by putting the right hand straight at the edge of the cap. Other commands were “links um,” which meant turn to the left, and “rechts um,” turn to the right, which had to be done in a certain way, using the heel of one foot and the tip of the other foot to turn and then to bring the heels together again. “Kehrt Euch” meant turning around 180 degrees, and “Ruht” meant relax by putting one foot a little forward and moving about freely. And there were many, many other commands, which we learned gradually. Then came exercises early in the morning for at least two hours, also exercises with the rifle, which were quite strenuous, running, throwing yourself to the ground, crawling, getting up, etc. Most of us regarded the exercises as healthy and also as fun.

We learned also many other things, for instance how to put your bed in order, how to clean your eating utensils and store them away,

At 9 o’clock in the evening at the signal of a trumpet, everybody had to be in bed. We sang songs while in bed and that seemed to be permitted. At 5 in the morning, the trumpeter woke us up, and everybody had to jump out of bed, wash up with very little water and soap, get dressed, put the bed in order, and get on the line for coffee and bread. At 6, we had to stand outside in line, while the major and other officers passed by, inspecting us. Then we marched to the exercise grounds, which was the grassland area between the Danube river and a dam, many kilometers long, the so-called inundation area, to prevent a wide area beyond the dam from being flooded. That was an ideal exercise field, and for the next few months we were there every day, except Sundays, for 6 hours till we marched to the barracks for lunch. I do not remember anymore, what we got to eat, probably a thick soup with some meat in it, beans, or noodles, or potatoes, and may be an apple in the end. There was usually then a rest period for two hours, and then we had to attend classes, usually about the regiment, a thick book containing all the rules in military matters which contained everything a soldier had to know. After dinner we sat around and talked, or sang, or played chess, or studied the regiment.

After the first 14 days, we were allowed to go home on Saturday afternoon for the weekend, and I took the long ride by streetcar home to my mother. I had a lot to tell her. Long before 9 o’clock in the evening, I was back in the barracks. Since I had the permission to sleep outside the barracks, I had rented a room in a house near the barracks, and so I slept in a comfortable bed. But I had to be very careful to get up in time, so that I would not miss the coffee, and be at 6 o’clock at my place in the row between my comrades, I had also to be careful to be before 9 o’clock in the evening in my room. No soldier was allowed to be in the street after 9, and cars with military police patrolled the streets frequently. Life was not easy, but I took it in stride. I was glad that I could go home on Saturdays to my mother and little Walter. I had learned that some boys could get a loaf of bread from the Sargent, whose duty it was to supply all the food for the kitchen. So, I tried too and for a very small amount of money I got from him a big loaf of commis bread. This I brought in a brown paper bag to my mother and made her very happy. Bread was rationed and very difficult to get. That I did every Saturday with few exceptions, when the Sargent had no bread left.

One morning, I had a mishap. A few seconds before 6 o’clock in the morning, a metal button of my coat — it was winter already — fell off, I was desperate, but found a way out. There was no time to sew it on. The button had a little ring in the back. So, I made a tiny hole in the coat, pushed the ring through and put a match through the ring. Unfortunately, a Sargent had seen what I had done, and reported me right away to the major. When the major inspected the company, he stopped in front of roe, and the Sargent showed him the match in back of the button. The major was furious, or pretended to be furious, and punished me right away with two weeks’ barracks arrest. That meant sleeping in the barracks and not going home on two weekends. It was hard. I had to sit evenings with the boys, who were mostly Hungarians, talk or play chess with them. I had learned to speak Hungarian and could communicate with them quite well. There came Christmas, and we had two days free to go home. I don’t remember how we celebrated it at home. Probably with a good meal and a good cake, made by my mother, and Else and her fiancée Franzi were probably present too.

In the war the situation had changed considerably since Italy had declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23, 19l5, and entered the war on the side of the Allies. Germany at once severed diplomatic relations with Italy, but did not declare war. It took more than a year till Italy declared war on Germany on August 28, 1916. On October 11, 1915, Bulgaria entered the war on the side of the central powers and invaded Serbia. England and France declared war on Bulgaria and so did Russia and Italy. The Bulgarians advanced rapidly deep into Serbia. The Serbs were in full flight into Albania, and the Austrians occupied Montenegro and advanced into Albania. King Nikita of Montenegro and Prince Wied of Albania had fled to Italy. The Serbian troops took refuge on the island of Corfu, which belonged to Greece, which was neutral.

On the Russian front the Germans were very successful and had taken all of Poland, Lithuania, and Courland. The front line ran from Riga on the Baltic Sea to Baranovici, Pinsk, Tarnopol, and Czernowitz. On the Italian front there were no major changes. The front was on the Isonzo river and there were in the first year four offensives by the Italians, but they were unable to break through. On the western front there were severe battles, four major offensives, but the Germans did not lose any territory, and the situation remained almost unchanged till the end of 1915.

I had only on weekends an opportunity to read the newspapers, but I followed the events with great interest. Big parts of Russian territory were occupied, Serbia was eliminated or rather crushed, and on the western and Italian front there were no changes. I became very optimistic, and my patriotic feelings increased. We believed at that time everything that the newspapers brought, that Austria-Hungary and Germany were attacked in a treacherous way by the enemies and that we acted in self-defense. The young people, all of them, were proud to wear the uniform and to contribute to the defense of the fatherland. The hardships of the military drill and the daily exercises were accepted as necessary, and we became used to it. There were some sadistic people among the instructors, sergeants and officers, who for some reason were never sent to the war front. They were a curse for the young people and were hated, but even that was accepted as a necessary evil.

We were now in the midst of a very severe winter, nevertheless, the drill continued. Many boys had frostbite, still we had to stand still, or lie in the snow and crawl. I became gradually sick, had rheumatic pains in the whole body, but never went to a doctor. When I woke up in the morning, my hands and feet were stiff, and I had to rub them to loosen the joints. Every evening I used an ammoniated gel, called Opodeldoc, an old medicine, which we had used as children, to rub around my joints. I did not know then, but I knew later that I had gone through a period of rheumatic fever. Still, everything else was fine and I accepted it.

But one day, a great change took place. Although there was a rumor for some time, the official announcement came to us as a shock. Having registered with the Infantry Regiment No.83 in Vienna had led all of us to believe that we will stay always with this regiment. But the regiment did not need that many aspirants for the degree of officers. There were many other regiments in Hungary, Bohemia, Croatia, etc, which did not have enough of these aspirants, which were called Einjaehrig-Freiwillige. One day came the announcement that many of us were transferred to other regiments, and among them was I also. 16 of us were transferred to the Infantry Regiment No.19 in Leva in Hungary, and we had to leave on January 21, 1916.

I had to bid farewell to my mother, Else, Walter, aunt Rosa, uncle Imre, and Alice. Uncle Imre gave me a long hug. He knew that he would not be alive anymore, when I will return.

Nothing could be done and we had to take the train to Leva. When we arrived there, there came another surprise. The regiment, since it had 4 companies, sent to each company 4 of us. But one of the companies was stationed outside of Leva, about 5 miles north in a small village, Nagy-Kereskeny, and that was the place, where I and 3 other boys, Kannheiis, Markasinski, and Buchsbaum, had to go. When we arrived there, we were shocked by that what we saw. It was a very small village, with small houses apart from each other, and the barracks were similar small houses. But wherever we looked, there was mud. There must have been before snow and ice, and since the weather was mild, it had melted and the result was mud. We had to walk through a sea of morass to get to the office to announce our arrival. There was a Sargent, to whom we gave our papers and who put down our personal data. He seemed to be friendly. We asked whether we would be allowed to sleep outside the barracks, and he gave us the permission. We were told that we would have to be at the rapport at exactly 6 o’clock in the morning.

It was late in the afternoon, and somebody showed us, where we could rent rooms, and we got there two rooms. Going there, we had to walk through mud, since there was mud everywhere. We were hungry and asked, where we could get something to eat, and an inn, the only one in the village, was indicated to us. The owner of the inn was a Jew, very friendly, and he lived there with his family, and they had a very pretty young daughter, who served us some food. There were many other soldiers there and among them also the Sargent, whom we had met before in the office. We soon went to our new sleeping quarters, and set the alarm clock for 5 in the morning, and went to sleep, two in a room. We rushed in the morning, washed up a little, got dressed and walked fast through tie mud to the barracks, hoping to still get some breakfast, and were on time to stand for the rapport in front of the first row. The officer, a captain and the Sargent behind him, came to us, asked a few questions and that was all.

The whole company then marched to the exercise fields, singing, as it was usual, military songs, in Hungarian, of which we did not know the words yet. Exercising was the same as before in Vienna. The commandos were in German. Everything was alright. The evenings we spent in the inn, and liked to talk to the young daughter of the innkeeper and his wife, who, if I remember right, also spoke some German. There was a lot of shoe-cleaning necessary when we came home, before 9, of course, and also of the pants.

One day, there was a mishap: The alarm clock did not work well and we got up too late. No matter how much we rushed and ran, when we arrived, the company was already standing in closed ranks, and we had to step into the open places. From then on, everything went wrong. The punishment was that we were not allowed anymore to sleep outside the barracks. We got a room where there were 4 long sacks, filled with straw, on the floor, one pillow each, also filled with straw, and a blanket. It was still winter and quite cold. For heating of the room there was a small iron stove with a tubs or funnel for the smoke, leading to the only small window. It seemed to us unbelievable, but that was the situation. No chair, no table, only a few nails on the walls for our cloths. We tried to make a fire in the stove, but had no luck. The wind blew into the pipe, and we got only smoke into the room. Pour men in a cold room, with straw sacks on the floor, which was an earthen floor. We asked the sergeant how we could heat the room, but we got only a short, snappy answer. No linen, no towels, no wash stand. We had to walk outside to a pump to wash.

Now we knew what we had not known before. We had heard the words “nemet” (German) and “nemetek” (Germans), and we soon knew that we were meant. We had not known before that the Hungarians hated the Germans. Later we heard also another word: “Zsido” (Jew), the “Z”s pronounced like the “J” in Jamaica. This had become clear to us by talking to some of the soldiers who showed sympathy and became friendlier. But only two of us were Jews, I and friend Mannheim; the other two not. But generally all 4 of us were looked at as enemies. There was nothing that could have helped us. We were in enemy country and had to endure it. We laid down to sleep in our cloths, and put our coats over the blankets to get some warmth. We had given up trying to make fire in the stove, since we only got smoke into the room, and burning of our eyes. They knew it when they gave us that room as quarters.

But it should get worse. One day they found that we had not cleaned enough our coats, that there were spots of mud on them. The punishment: Arrest for one night, which meant sleeping in a small, narrow cubicle, into which we had to crawl to get inside, and which was inside not high enough to stand up. We were later told that this was once a pigsty. We had to sleep there on straw without any blankets. But we slept anyway, and the next morning we had to brush the straw out of our hair and of our uniforms.

One day, they found something else wrong and there was again punishment, especially severe. This same Sargent took us out in the late afternoon for special exercises. For about two hours, we underwent the most strenuous exercises. We had to run in the mud, then we were ordered to kneel down, to get up, to lie down, where there was especially much mud, to get up, to lie down again, then to run again and so on. This went on for two hours. He enjoyed it, how we got dirtier and dirtier, and out of breath. Then we had to go home, that means to our barracks. Cleaning of these coats seemed impossible. With a knife we could scrape off thick layers of mud, and then we had to hang the coats up for drying. Early in the morning, we started to brush the mud away, and to clean our rifles, which were covered with mud. We still looked quite dirty, when we stood in close ranks and went out to the morning exercises. Behind all that was, of course, the captain, We knew about him as well as about the Sargent, that they were never out on the front, that they always stayed in the “Hinterland.” There were great many such people in the army, people who had special connections. We used to call them “Drueckeberger”, which means people who stay away from danger.

One day we read in the regiment, a book that contained everything about military matters, that a soldier has the right of complaint to the highest officer in the regiment about injustices. I proposed to my colleagues that we should ask for a hearing of a complaint before the commander of the regiment, who was a colonel. Our colleague Markasinski was against it, was afraid that we would all end up in jail. I did not let go, and went into the office and asked the Sargent whether there was a possibility to put in a complaint. He said that it was possible, but not more. A complaint that they had put us for a night into a pigsty, and that our room was without heat, and that we had to sleep on strawbags which were on the floor, would have had a strong effect. We expected now that they would make a counter-move and it came very soon.

One day, we were told that we were punished with one week of jail. The reason given was undisciplined behavior. All four of us were transported to Leva, and put there in a prison behind bars. But it was a clean room with beds, and we were rather happy. We could rest there and were treated nicely. Our colleagues from Vienna, 12 of them, who were transferred together with us, came every afternoon to the window and could not believe their ears when we told them what kind of treatment we had gone through in Nagy-Kerelskany. They brought us every day good things to eat, like cookies, candies, chocolate, etc. They told us that they were treated nicely, and that they soon will be sent to an officers school in Esztergom.

We felt sorry that we had to leave the jail and go back to Nagy-Kereskeny. When we arrived there, there were quite a number of aspirants there, Hungarian boys, about 10 or 12, who had gotten two big rooms with newly made beds with mattresses. We had to return to our room, where the straw-filled sacks were on the floor. We were told that we will be further punished, that we will not be sent to the officers school, as we don’t deserve it, but will be sent to the battle front with the next field company, which was just being formed. The other 10 or 12 boys were getting ready to be sent to the officers school. We were not unhappy, since that was the fastest way for us to get away from that place, which was hell. It is unnecessary to say that my patriotism had reached a very low level on account of that kind of treatment.

And so we left on May 7, 1916 for the Russian front. It was a long train ride. We passed Tokai, a place famous for the wine, and many of us got out and bought a bottle of Tokai wine. Then the train took us further east to Munkacs and then north through the Beskid Pass in the Carpathian Mountains to Galicia. The train stopped for a long time in Stryj, where my uncle Martin Sobel and aunt Klara lived. This was the city where Else and Carl were born, and where I spent two months of vacation, when I was ten years old, exactly eight years ago. I figured that the uncle was probably as a pharmacist in the army, but I sent a messenger into the town with a little letter, telling my aunt that she should come to the train station, if she wanted to see me. She did not come and the train left. She later told me that she had received my letter, but that she could not come to the station.

The Russian Front

The train continued to Lemberg, and further east to Zablotce, where we got out. From there we marched to the front line, which ran straight from Brody in the north to Tarnopol in the south. We went first to small barracks, which was the reserve position of the regiment. There everyone of us had a place for sleeping, one man next to another one, in two layers. I had to crawl up to the upper layer. It was summer and the weather was nice. We were about half a mile behind the front line.

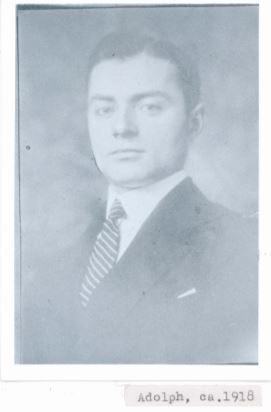

The next day, after our arrival, the colonel, quite an old man, over 60, came to inspect the newly arrived field company. When he came to me, I saluted, standing straight, and said: “Einjaehrig-Freiwilliger Adolf Mechner.” He looked at me but did not ask me anything, for instance why I had not gone through an officers school, since I did not have a little white star on my collar. I knew right away that he was informed about us by the captain in Nagy-Kereskeny. I should say misinformed. It did not matter. Our new commanders, the 1st and 2nd lieutenant, and the captain, whose name was Steinitzer, and all the soldiers were very friendly towards us. It was a different bunch of people. By now, I spoke already quite well Hungarian and sang with them the Hungarian songs. It was a relatively quiet part of the front, stationary for months. Artillery fire was quite rare, but at night there was constant infantry fire. But we were in a relatively safe place, behind a little hill. Very soon, I was full of lice.

About a week later, we went into the front line, that means into the trenches, and the troops which had been there came into the reserve, our barracks. That was the usual thing, that such changes were made every three weeks. A completely different life began for us. The trenches were just deep enough that a man, standing straight, was fully protected against rifle fire, except for the place where he had to put his rifle in order to shoot, where there was a little less soil. The walls of the trenches were strengthened by a kind of wicker work, held up by posts, which were rammed vertically into the ground. This required, of course, constant repair. Things got bad when it rained. Then we often had to stand in mud. What I did not mention was that we all had high boots, which gave us much protection. The trenches were wide enough that people could pass easily behind a man who was leaning against the front wall of the trench. The distance from one man to the next one was about 1 ½ to 2 yards. The front line did not run a straight line, but rather in a zigzag, each branch about 15 to 20 yards long, so that the tip of the zigzag line was nearer to the enemy line. This was important for the defense, allowing flanking attacks or defense. A few more details: There was usually a second trench line parallel to the front line, some 10 to 20 yards behind, connected by running trenches with each other, of importance in case the enemy succeeded in an attack and invaded the first line. This second line was, in hilly terrain, a little higher up on the hill for easier defense. Another important detail was that the trenches did not run in straight lines, but were interrupted every 8 to 10 yards by a higher mass of earth, and the trench ran in a U-shaped form behind that hill, which was only 5 to 6 feet wide. This hill was important, as it offered protection against artillery attacks coming from the side, and especially against shrapnel’s and hand grenades. Especially bad were the nights, since we had to shoot constantly, and the Russians did the same. It was fear that the enemy may have come out of the trenches and come closer to us. We saw nothing, only the grass against the sky, and that gave the impression that the Russians were coining. In reality it was the grass moving in the wind. But we were not sure, and therefore there was a constant shooting going on from both sides, and an enormous waste of ammunition. That was going on every night. With daylight the front became quiet, and that was the time when we could lie down to sleep, along the trench wall, with the knapsack under the head. I had something special, a little pillow which could be blown up, which I had brought with me from Vienna. It was terribly dirty, but that did not matter, since it was soft. Not everybody was allowed to sleep during the day. There were always some people on guard duty during the day. Once a day they brought food, a thick soup with pieces of meat, beans, potato, and what have you, then a big piece of bread, a piece of sausage, a cup of coffee. That was all for the whole day.

During the day there was more artillery fire, since it was easier to see, where shrapnel or a grenade went and exploded. The noise, which a shrapnel or grenade made when coming toward us, is difficult to describe. When it flew over our heads, it was a loud, whining noise, getting at first gradually louder and then less loud, and then came the explosion. But it was different with projectiles coming straight toward us. Then the whining noise was almost missing, and we felt the pressure in the air, and we knew that we had to get down within a second to get some protection. That goes for grenades. With shrapnel’s it was different, since they were shot in such a way that they exploded in the air in front of us over our heads, so that a rain of heavy lead bullets, each the size of a cherry, came down with great force. It could not perforate the helmets, which we were wearing all the time, but otherwise it could cause terrible wounds. There was only a second left to go down to duck behind the trench wall. With the bullets there came also heavy pieces of metal down, the cover of the shrapnel, which could cause terrible injuries. But, as I said, this part of the front was stationary, and we got relatively little artillery fire.

The three weeks on the front line had passed, and we were pulled out and went into the reserve. Life there was in general pleasant. There was a brook nearby, and we could go for a bath when we wanted. There were no airplanes in use at that time, and we never saw one. But the Russians had so-called captive balloons, which were all the time in the air far behind their lines, in the shape of a Zeppelin balloon, from which they observed us. They must have seen us bathing and one day suddenly a few shrapnells exploded over our heads. They did not aim very well, and nobody was hurt. But we ran away fast.

I got a special mission when we were in reserve: To walk every morning over a hill to the regiment’s commando with the regiment’s report, which I had to bring to our commander, captain Steinitzer. This was only unpleasant in rainy weather, otherwise I liked it to walk through the fields, where flowers were in full bloom. Often I found there Russian infantry projectiles on the ground, which I collected in my pocket. They were pointed, whereas the Austrian projectiles were round at the top. Captain Steinitzer often held conferences, in which he discussed the general war situation. Among other things he told us not to take prisoners, but rather to shoot them, even when they were without a rifle with both hands up. He said it was too expensive to take care of prisoners. I came later into such a situation a few times, and did not follow his advice. One day, I was promoted to the degree of Gefreiter, which means lance corporal, and now I had a little white star on each side of my collar.

Captain Steinitzer found out that I could play on the piano, and from that day on I had to go every evening to his quarters, where he and the other officers, 2nd lieutenant Géza von Táhy, 1st lieutenant Žiža, a Yugoslav, cadet Pesti, and ensign Vid, also a Yugoslav, were assembled and drinking. Captain Steinitzer was a heavy drinker and got drunk every evening. There was a piano and I played for them whatever came to my mind, and they all sang, mostly student songs, popular operetta music, folk songs, etc. It was much fun.

One day, the whole regiment had to move. It was raining all day, and we had to walk with our heavy knapsacks, rifles, small shovels for digging in, bayonets, ammunition, etc. On top of the knapsack was the coat, but this time we had to wear it, and below the knapsack was a rolled-up blanket. We walked from morning till late in the evening, and slept then in an old school building. The officers were riding on horseback, but we others had to walk, carrying an enormous load with us.

Retreat

We were not told where we had to go. Later we found out. Since the beginning of the year, when I was transferred to a regiment in Hungary, I was not anymore informed about the situation in the war. I did not know, for instance, about the terrible battles in France at Verdun, where hundreds of thousands of people lost their lives. Verdun withstood, although almost completely surrounded by the Germans, and was never taken. There was also a great battle on the Somme River, where tanks were used by the English for the first time. They advanced, but did not gain much terrain and had great losses in men.

What we did not know then and what I learned later was that the Russians had launched a great offensive under general Brusilov and had advanced over a front of 300 miles. The Russians took Lutsk on June 8th in the North, and Czernowitz on June l8th in the south, and heavy fighting continued about Kovel, Tarnopol and Baranovici. Tarnopol was the area, where we were. The Russians advanced from 25 to 125 kilometers in that area, and we were retreating. We were moved north to cover the retreat, and had to go into position between Radziwilov and Brody. These two cities were for over 100 years border cities, Radziwilov in Russia, and Brody in Galicia, and the border running from north to south between these two cities. It took the whole next day of marching, till we reached that point. The rain had finally stopped, and in the late afternoon we had to spread out to form a line, and to start digging in. It did not take long and we were not yet deep enough, when the Russians had come closer, and started with artillery as well as infantry fire. One of my best friends, a fine Jewish boy, from Hungary, whose name I have forgotten, was one of the first to lose his life. We had to run, and had to leave him behind. After running for about one mile, we had to stop, spread out to form a line and dig in again. Just in that moment, when I was standing there with about 10 or 12 men, a shrapnel exploded about 10 yards above us, and a rain of bullets came down. Many were wounded, but, miraculously, I was not hit. The line was rather thin, as we were about 10 feet apart, and we started to dig in. My hole was about a yard deep when the Russian artillery started to shoot. But our artillery responded and we had quite a number of machine guns also. Each of us was supplied with a great amount of ammunition, and we prepared ourselves for a fierce battle.

Behind our line was a wooden fence, and some of our people had removed some boards of the fence in order to be able to move through, I had not gone through any of the holes in the fence. It was dark anyway, and I was busy digging and deepening my hole. We were ordered to call all the time the name of our company, to make sure that the line was intact. The call came from the right and continued to the left.

Behind us was the city of Brody in flames, so that we were not completely in the dark. It was about midnight, when we started to receive massive artillery fire. We knew that that was the beginning of the attack. And then the Russians started to move. We could see them and we could hear them. They all shouted and ran. It was the first time in my life that my knees shook, and I could not stop the shaking. Their shouting came closer and we all started to shoot. But then, suddenly, when they were in the middle of the field which was between us and them, our artillery started to shoot. The Russian tactic was always to send many lines of men, one after another one, up to 16 lines, forward. It was called the Russian steamroller. The idea was that the first lines will not reach our lines, but the last lines will come close and overwhelm us. They came very close to me, many of them up to 10 or 15 feet distance from me. But I was a sharpshooter, and each of them received a shot in the head. After being hit, they usually ran a few more feet till they fell, and often I was afraid that one of them would fall over me. Fortunately, they could not run fast in the dark, as there were many people lying on the ground. I also had the advantage of being near the ground, while they were exposed. Behind us, the city of Brody was burning, so that the sky was lighted, and I could see the silhouettes of the men with the hand grenades clearly, and so they were easy targets for me. It was, of course, self-defense. Hand grenades are terrible weapons. The recoil of the rifle caused me severe pain in the shoulder, and I had to put a piece of rag into my blouse to lessen the pain. I had to shoot very fast, as they came closer and closer all the time.

Suddenly, I lost contact with the man to my left, and I guessed that the Russians may have broken through. I went for a moment to the back to my commander, lieutenant Ziza, and told him that. He sent me with another man to find out what the trouble was. We went along the wooden fence and saw that many boards of the fence were missing, and there were Russian soldiers standing and shooting. We turned and ran, but they had seen us and turned around and shot. But I was fast and bending forward while I ran, but unfortunately, the other man who was with me got a shot in his shoulder. We went back to our lieutenant, and he sent me with a detachment of a few more people, whom I showed the way, and we all threw hand grenades at the Russians. There must have been very few, and they were silenced. We then restored our line for the rest of the night.

When I came back to my hole, I saw dimly a man lying there and moving. He said something what I understood meant: “Don’t shoot,” and he put his hands up and crawled out. I threatened him by holding my rifle towards him, but he had no rifle. This was my first prisoner I had taken, a very young, good-looking boy, whom I took over to ray lieutenant, and I went then back to my hole. The attack was in general repulsed, and the rest of the night was quiet.

When daylight started, we saw a terrible picture: Hundreds of dead and wounded lying in front of our line. We stuck out a white flag, and so did the Russians, which meant no shooting, so that we could bring in the wounded. I went out with our Red-Cross men with stretchers, and what we saw is difficult to describe. Besides many dead, great many severely wounded men. The men lying before my hole had all shot; wounds in the head. The worst massacre was done by our artillery. One wounded officer made me cry like a child. He had his lower leg hanging on a tenders, and when they put him on the stretcher, I lifted his leg up and put it next to him, and he pointed to a big hole in his coat and that meant that he had also an injury in his abdomen. He was such a good-looking, very tall man, very pale on account of the great loss of blood. Among the wounded and dead were many, who stood up and put both hands up, people, who had been hiding and waiting for the right moment to show that they wanted to be taken prisoner.

The date was the 2nd of August, 1916. Everybody was digging in, making connections from one hole to the next one. We were all sleepy, since we had not slept at night, and very hungry and weak, since we had not eaten anything the day before. I was now in a sector more to the right, and there was a two-story building behind me. I went there to go inside, and to my astonishment there was a good piano there on the second floor, and I played a few pieces on it.

Just then, the Russian artillery started to shoot, and it was good that I had gotten out of the house, because they directed the artillery fire at that house, and soon it started to crumble. Just as we moved away in our trenches, which were close to the house, a big piece of the wall fell down, very close to me, and I was struck by a few bricks. I felt a severe pain in the middle of the back, and also in my right knee. We moved away from that house, since there was danger that it would collapse completely with a few more artillery shots.

I moved as well as I could, in severe pain, to my old hole from the night before, where I had my knapsack. I fell soon asleep or rather collapsed. They then brought the food for the day and I ate, the first time after two days.

I noticed that there was very little shooting of our artillery, but much shooting of the Russian artillery and infantry, and we had to stay now all the time in the trenches. The noise was enormous. We expected a second night of an attack by the Russians, and I could see the fear in everybody’s face. We got a lot of ammunition. It got dark, and very soon the hell broke loose. Heavy artillery fire and the shouting of thousands of men, the same shouting as the night before. We had no artillery and only a few machine guns. We shot as fast as we could.

A messenger came and I remember his name, Haidinger, and it was from lieutenant Ziza. The message: All our troops will retreat, but I and a few men, 8 or 10, should stay behind and shoot as much as we could and then surrender. I was flabbergasted, as I saw the end of my life. As soon as he left, I knew what I had to do: To leave also with all the others. The shouting of the Russians was already very close. I did not know where to go, since I had not known the terrain behind our lines. I had to climb soon over a fence, and there, with me, also climbing over the fence, was Haidinger, “Mechner,” he said, “you were supposed to stay behind.” I said to him: “Nobody has the right to tell me to surrender.” And I ran. It was pitch dark, and I ran as fast as I could. I came to a river, and I later found out that it was the Boldurka river. Should I now go to the left or to the right, I asked myself. I decided to run to the right along the river and after a while, to my amazement, I came to a bridge, a wooden bridge. There were a few men there, putting hay on the bridge, and pouring gasoline on it. They called me to hurry, and there came a few more people, and in the next moment the bridge was on fire. What enormous luck I had.

This was one of the smartest things I had done in my life—I was 19 years old—to disobey an order of a military commander. One of the worst sins. To become a Russian prisoner seemed unacceptable to me. The Russians were known not to take prisoners, to prefer to shoot them instead. That was much simpler for them. I made my decision fast. The Russians were very near already, their voices had become louder. Our artillery was gone and our machine guns had stopped shooting a few minutes before. So, I knew that everybody was running. So, I went too. The Russians may have been 20 feet behind me and I had to run very fast. There were none of our people next to me. When I came to the river, I had to decide fast whether to go right or left. I decided right and it happened to be good. There was the bridge and I got there one or two minutes before they started to put it on fire. All luck!

As a Russian prisoner, if they would not have shot me right away, I would have been sent to Siberia, would have starved to death or frozen to death. It was 1916 and the war ended in 1918. In 1917 the Russian revolution had started. Many Austrian prisoners had been sent back to Austria after the signing of an armistice. If I would still have been alive then, I would have been sent back to Austria. So, I had made the right choice at the right moment at the right place.

We came into a village, and there were thousands of men, shouting their regiment’s numbers. I found a few people of my regiment, and we walked together. I had severe pains in my back and I was almost certain that I had there a broken bone. And my right knee was hurting too, and I was limping. I was so weak and exhausted that I had to lie down at the edge of a road to sleep, and the others did the same. By daybreak, we moved on, and soon found a few more people of our regiment.

But the pain was intense, and I was looking for a health station, and finally found one. I was examined and was told that I had to go to a hospital. I was put on a horse-drawn vehicle, together with a few other people. It was a long ride to the railway station Zablotce. I was sleeping all the time, and when I was put on a railway car, I soon fell asleep again. There was a man in the ear, which, by the way, was a cattle wagon, who was supposed to take care of the wounded. That he was a thief, I found out when we finally arrived in a hospital in Przemysl. My knapsack was almost empty, and I had a few nice things like a good pocket knife and other things, which were not there anymore.

When I arrived there, I told them that my regiment was the Infanterie Regiment No.83. I had had enough of the Infanterie Regiment No.19. I was examined quite thoroughly, repeatedly X-rayed, and no fracture was found. In the knee it was only a severe sprain. The back pains became less severe, and after about a week they were practically gone.

Convalescence

I was told by people who shared the room with me that I often cried and yelled out of my sleep. I believed them, since I was aware that I had bad dreams, which often woke me up. It was always the yelling and shouting of the Russians, when they started an attack. Perhaps they had shouted “hurrah” or a similar word, but it was nerve-racking and made my knees shake. It was a terrible experience and came every night back as a dream, also the humming and whining noise of the grenades, ending with an explosion, which woke me up and made me yell. The doctor who treated me called it a neurosis or something like that, and I received pills for the night, which did not help. Since that was not serious enough to keep me in the hospital, where they needed beds for more serious cases, I was released from the hospital after about 10 days, and sent back to my regiment No.83 in Vienna, with a recommendation for further treatment of my neurosis in a convalescent home.

I was happy and so were my people at home, when they saw me, my mother, Else, Walter, and all the others. My dear uncle Imre had died in the meantime. I had a most pleasant life then for a few months at home. Twice a week, I had to go for a cold water treatment, which consisted of a warm shower, a luke-warm tub bath to which cold water was gradually added, and then a cold shower. At the end, an ice-cold wet linen sheet was wrapped around me, I had to lie down, and was covered with blankets and had to rest for one hour. This was done twice a week and continued for 4 months. I enjoyed the treatments very much, although I really did not need them. The bad dreams continued for years. I enjoyed being in Vienna. I went to museums, to libraries, to the opera, to shows, to concerts, read a lot, visited aunt Gusta and cousin Isa, who lived now in the same house in Margarethenstrasse 50, also aunt Rosa and Alice, who had moved to another apartment in the Lederergass in the 8th district.

Else had her little apartment also in the same house where my mother lived, and I saw her very often. Her fiance Pranzi Lang and his parents also lived in that house. Else was always very religious, and had converted in 1910 to Lutheranism. She went often on Sundays to church, and loved the sermons and lectures of the pastor. I went once or twice with her, but was not very impressed.

I had not mentioned yet that my mother was often ill, had suffered from gallstones. For many years, when I was still a little boy, she had severe gallstone attacks, usually accompanied by yellow jaundice. Over the years, she had undergone many kinds of treatment and once, before she married my stepfather, she went to the spa Karlsbad in Bohemia for a few weeks. During the war, while in Vienna, in 1916, she took courage and underwent a gallbladder operation at the clinic Hochenegg. The gallbladder and about 80 stones were removed, a few big ones, and she recuperated nicely.

On the war front, there were many changes in the meantime. On the Italian front, there were another 5 offensives on the Isonzo, the 5th on February 15 to March 18, the 6th on August 6 to 17, the 7th on September 14 to 18, the 8th on October 9th to 12th, and the 9th on October 31st to November 4th, all terrible battles with severe artillery bombardment, which was called drum-fire, but all without substantial change.

On August 27th 1916, Rumania declared war on Austria-Hungary, and began the invasion of Transylvania, occupying Kronstadt and Hermannstadt. But soon the situation changed, and Austrian and German forces invaded Rumania, and the capital Bucharest fell on December 6th. The Rumanian government had moved to Jassy. There were further advances and soon most of Rumania was occupied.

The emperor Franz Joseph I had died on November 21st, and was succeeded by his grandnephew Carl. I remember that I went late in the evening to see the coffin passing through the Mariahilferstrasse, being taken to Hofburg. Great many people were standing there, many of them crying. He had been the monarch for 68 years.

Toward the end of the year 1916, President Wilson, who was just re-elected, tried to intervene, and proposed to both warring sides “peace without victory.” Negotiations went on for weeks, proposals and counter-proposals. The Germans felt that they were in a relatively better strategic position since the collapse of Rumania, and made proposals which were difficult to accept. Negotiations continued into 1917 when, on January 8, the Germans decided that unrestricted submarine war would be the only method by which England could be brought to her knees, and the war won. President Wilson was already under pressure, since the Germans had sunk the Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, with the loss of 1198 lives, including 139 Americans, on May 7, 1915. The sinking of the Lusitania had brought the United States and Germany to the verge of war. Now the United States was notified by Germany that unrestricted submarine war would start on February 1, 1917. The United States severed relations with the German government. Soon American ships were in fact sunk during February and March 1917 after the sinking of the big liner Lusitania. On April 6 the United States declared war on Germany, war was not declared on Austria-Hungary until December 7, 1917.

Officer School

As to myself, my treatment was ended, and on December 16, 1916 I returned to my regiment in the 21st district of Vienna. On January 2, 1917, I was sent for 3 months to the officers school in Bruck-Kiralyhida, which was in Hungary, near Pressburg, and not far from Vienna.

It was a severe winter, and training was very strenuous. We were over 100 boys, most of them from Vienna, and we all took the treatment in stride. At 9 o’clock, everybody had to be in bed, and the lights were turned off. Then we all started to sing, and that went on for a long time. We needed the sleep, since we had to get up at 5 and stand in closed ranks at 6 o’clock. In that one hour we had to get dressed, wash up—which was usually impossible, since the water was frozen—have the breakfast, and put the bed in order. About that they were especially strict. We marched out singing, when it was still dark, to the exercise field. The exercises were extremely strenuous and continued for hours. They started with movements of the head, and arms and legs, turning of the body, and combinations of all these movements, kneeling, lying down in the snow, all kinds of exercises with the rifle, swinging it up with both hands, and at the same time spreading the legs apart, and, of course, in the end running for long stretches. There was usually a pause for 10 or l5 minutes, and then the exercises started again. That went on till noontime, when we finally marched back to our barracks for the lunch. There was one hour’s rest in the afternoon, when everybody had to keep quiet. Then classes started, and we had to sit and listen to lectures about military matters. Then came dinner around 6 o’clock, and afterwards we were free to do whatever we wanted, read, play chess or card games, etc. At 9 o’clock, we had to be again in bed.

On Saturday afternoon, we were allowed to leave and take the train for Vienna, and then we were really happy, when we could get home and see our loved ones. But on Sunday night, we had to be back at 9 o’clock and in bed. I had to take the street car No.13 in Vienna, to get to the Ostbahnhof, and I usually left the house at 5 o’clock.

One Sunday, I had bad luck. There was much snow in the streets and the streetcar No.13 did not come. I waited over one hour, till it finally came. I just made it to the train station, but there was no time to buy the ticket. The man at the door could have let me go through without the ticket, since I could have paid for the fair the conductor in the train. But he was stubborn, and I had to stand there and see the train leave. I had to wait now 2 hours or so for the next train, and I knew that I would arrive late, exactly at 9 o’clock. I had to run a long way from the train station to the barracks, and while I was running, I heard the bugler blow his horn, what meant that it was 9 o’clock. When I arrived at the barracks, the sergeant had just finished the inspection, and had, of course, noticed that I was not in bed. I explained to him the mishap with the streetcar, but to no avail. He put me on the list, and I had to appear the next morning for rapport. I explained to the captain that I had waited for over an hour for the streetcar, and on account of that had missed the train. Nothing helped; I was punished with withdrawal of the privilege to go to Vienna for one weekend, or perhaps two, I don’t remember anymore, which was a hard punishment.

At that time, my rheumatic pains had gotten very bad, and I had especially bad pains in my feet. The winter was very severe. I went for a medical examination, and the doctor put me for two weeks in the hospital. That helped and the swelling of the feet subsided. On March 31st, the course in the officer’s school ended, and we all went back to our company in Vienna. On April 16th, I advanced to the rank of Corporal, which meant that I had now 2 white stars on each side of my collar.