I was born in Brooklyn on July 5, 1941, but my first house was in Neponsit, near Riis Park in Rockaway. We lived with my mother’s eldest sister, Henny, in a large house right on the beach, until we moved to Washington, D.C., where my father had a job with the Norden Bomb-sight Company. (For historical information, consult my father, Oscar C. Weitzberg, and my mother, Mary Weitzberg, nee Rosenberg. I will plead ignorance based on my extreme youth at the time.) We moved back to Rockaway on Columbus Day, October 12, 1944, into the house in which my parents still live. There I spent virtually all my time, except for three summers at camp and one summer traveling in Europe and Israel, until I went away to college in the fall of 1959.

My brother Abe is six years older than I am, and my sister Laura Ruth is three years older than I am. We spent a lot of time fighting — or play fighting — as the young of all species do to practice for later on. I didn’t really get to know or appreciate either of them until we were grown. During the summers, we were part of a whole neighborhood gang who played stick ball and stoop ball and put on plays and wrote newspapers when we weren’t on the beach building sand castles or playing ball. The beach in those days was nothing like it is today. There was no broken glass to worry about, no dogs being walked on the sand. Beach chairs were made of wood, not aluminum, and so had to be stored all summer right on the beach, being protected, set up, and taken down by young men whose first job that often was.

I never learned to swim very well, since the water was too rough for me to venture out beyond the breakers where the water was calm enough for real swimming. And I couldn’t very well go out beyond the breakers if I couldn’t swim. So, despite some lessons from lifeguard Tommy, and three summers in summer camps where there was instruction in lakes, and having our own swimming pool now in our house, while I can swim, I still don’t feel comfortable in the water. It’s still a struggle for me.

We went every Shabbos to synagogue. I loved the songs, even when I was three. I suppose I was a cute distraction to the children who sat in front of and behind our pew. I think our circle of acquaintances — mine at least — was limited to the rows on our side of the synagogue. While I feel a close bond with the Kirwins, Korns, and Engelhards, I can’t even think of the names of people who sat on the far side of the enormous room. Similarly, our social contacts centered around the Sisterhood, in which our mother was active, and the Temple, in which my father was active and still is today. I don’t recall ever having a baby sitter. My parents were quite content to stay home with us; my mother especially, having been orphaned when she was ten, gloried in the family togetherness she missed as a youngster. And much of our time was spent in gatherings of the families of my mother’s three sisters, who lived in Brooklyn and Forest Hills. I was the youngest of all ten Rosenberg-sister grandchildren. The next youngest cousin was a full three years older than I. I recall my mother’s telling me that her sisters thought she was crazy to have a child with the world situation so unsettled. I’m glad she had me!

I was a good student, well-behaved and attentive, and therefore generally learned things upon first hearing. So I did well and my teachers always liked me, even though (as I later realized) I wasn’t developing any good study habits. My fourth-grade teacher was an artist and encouraged me to draw and paint. I had talent but no drive or persistence and didn’t develop any real skill. Similarly, though I took piano lessons for about ten years (from the time I astonished a recital audience at age five by playing by ear the piece my brother had just performed to show off the results of his lessons), my attitude was one of resisting lessons. So, I didn’t practice, “got out of” having to do challenging pieces, and really never had much to show for the time and money invested. I do still love music, and have a good critical ear, developed partly at Swarthmore, where I took some rigorous courses in theory, and partly from being surrounded by music ever since I met Francis.

I never took ballet lessons, partly out of lack of interest, and partly because my sister didn’t like them. But I did go to Hebrew School. I think I went from the time I was six (2-3 x a week) till I was 15 or 16 or even older. I became very religious, that is, observant, when about 16. Laura did also at about the same time. We made life very difficult for my parents, constantly criticizing them for minor infractions in observances. I never did understand why if it was important to keep the house kosher, it was all right to eat lobster in a restaurant. I was given a marvelous opportunity to go to Israel and Europe the summer of ’57, with a group of high school students. A boyfriend of mine had been there the summer before, and his enthusiasm was contagious. I really fell in love with the dynamic kibbutzim and the pioneer spirit, and fully intended to return as an immigrant someday, to help build the country. Reentry to materialistic New York was difficult — for a few weeks — but once back, I quickly got used to this society again and didn’t think further about emigrating.

A strong influence on me was my grandfather, Isaac Weitzberg, who came to live with our family when I was about seven, after having had a stroke. He’d been widowed when I was a few months old, and he’d moved to Washington to be with us while we were there, but his brothers and sisters were in New York, and all his ties to the old country, so he lived in Brighton Beach until ill health overtook him.

He was very quiet and unassuming, very loving, and would help people in any way he could at every opportunity. He loved to play cards and spent many hours patiently playing with me, gin mostly, I think. He wasn’t a great talker, and he’d never learned to read or write English, having worked hard ever since he immigrated to the U.S. But he was wonderful to have around.

One teacher I had in seventh and eighth grades influenced me toward science and encouraged my problem-solving approach. The same teacher suffered greatly for his involvement with his students, even while he inspired us and our curiosity. Two other girls and I published a silly, gossipy newspaper, the Every-so-often Blabber. Mr. Blechman was kind enough to run the paper off on the school ditto machine for us; we supplied stencils and paper; the school supplied the ink; he supplied his labor. It was fine in P.S. 44, but then in the middle of eighth grade, we switched to the brand new J.H.S. 198. The principal there was a real martinet and couldn’t stand his (Mr. Blechman’s) maverick nature and independence. So the principal brought Mr. Blechman up on charges and had him transferred out of the school. The charges today seem ridiculous: that he showed bad judgment in encouraging our newspaper (which the principal’s dirty mind read things into), that he showed bad judgment in using school property to duplicate it; that he used profane language in the presence of other teachers, and so on. For me, it was an introduction to the real world of petty bureaucrats and small-minded, power-hungry nothings. But for Mr. Blechman, it meant permanent removal from a teaching environment in which he thrived and in which his students thrived. Teaching, far from home, in another district, was never the same for him.

My interest in science continued to grow, partly because I enjoyed solving riddles and problems, and partly because the other subjects were taught in such a rote, passive way. I fully expected to become a scientist, and it was only when I reached college that any other possibility entered my head. For one thing, the other subjects were taught in an exciting way. For another, the sciences — at least at the entering level — were taught in a mechanical way. It was more as if the departments were screening out the real, ready-made, full-blown scientists, separating the sheep from the goats. I had expected more support and encouragement than I got. It was three weeks between the time I took my first physics exam and the time they returned the papers or even posted the correct answers. By then, I’d decided physics wasn’t for me.

Something even more important happened though. I noticed that there was absolutely no correlation between the grade I earned and the value I got from a course. I got only C’s in philosophy and history the first semester, and yet whole worlds opened to me and I learned more than I ever had before in such a short time. I got A’s in calculus and English literature and learned absolutely nothing of value. So my eagerness to excel academically disappeared. I had a choice to make between “their” values and my own values and decided to go for growth instead of grades.

By the spring of my sophomore year, I’d decided to major in psychology. This was largely the result of a course in experimental psychology that I took with Prof. Hans Wallach, one of the pioneers in the “Gestalt psychology” movement of the ’30 s. Looking back, it was a silly course, since it was all “armchair experimentation.” That is, it was all thinking about experimental design and drawing conclusions from experiments that we never got to do! Still, it made me appreciate Francis all the more when I met him in the spring of ’61, the end of my sophomore year.

I had worked the previous three summers as a lab assistant in the otology department at NYU-Bellevue Medical Center, doing a combination of histology, animal handling, and statistical work. My boss, Joseph Elmer Hawkins III, M.D., was doing research on the effects of nutritional deficiencies and various antibiotics on hearing. We looked for physical evidence on damage to the inner ear (hair cells in the cochlea mostly, also in the semicircular canals) both in the rats and guinea pigs we treated, but also in human patients who died without any families to bury them. Many of them had been treated for years with streptomycin, and the damage we saw was enough to scare me away from taking any kind of drug at all. I do not like to be a guinea pig for the years it takes for scientists to discover side effects!

We also looked for behavioral evidence of hearing loss. I did some audio-metric work once a week one summer at the people-part of Bellevue, the hospital. It was a very depressing work environment, and I have done all I could to stay out of hospitals ever since. There were also three people working in a separate lab to get measures of rats’ hearing thresholds. By coincidence, their procedures had been designed by one Francis Mechner a few years before!

I had learned a lot in those three summers, not only technical and scientific things, but what it’s like to work in a large organization or even a small office. I was disappointed by the lack of alignment toward a goal. More energy was expended in earning points with the boss or increasing the budget than in accomplishing anything. I had an idealistic view of what a lab should be like, and the real lab disappointed me. The two histologists were always arguing — in Polish — about who was worse, the communists or the Nazis. The husband of one had been imprisoned by the Russians; the husband of the second had been imprisoned by the Germans. And their disagreement on this one point poisoned the atmosphere in the entire lab, at least for me. So by the spring of ’61, I’d had enough of the otology lab and thought that it would be nice to work closer to home (It was a 90-minute commute each way from Neponsit to Bellevue), and took the public service exam to be a post office worker. I had dreams of making a fortune ($80 per week) while still having time to play with my friends on the beach.

Then, when I was home from Swarthmore for spring vacation, I spoke with my good friend Jordan Rosenberg, a math whiz from my high school class. He was a student at Columbia University at the time. He told me about the interesting work he had writing “programmed instruction” math courses for some psychologist who lived in a bachelor apartment on Riverside Drive and worked over a Chinese restaurant. It sounded much more interesting than carrying sacks of mail, so I asked Jordan if he thought his boss would need another programmer for the summer. He didn’t know but promised to introduce me to his boss — Francis Mechner was the name — when I visited him at Columbia that week. Jordan explained to me what programmed instruction was; he even showed me some index cards on which Mechner had written some things about how to program. I fell in love immediately with the neat European handwriting! And I was charmed by the twinkly-eyed flirt to whom Jordan introduced me briefly. He couldn’t promise any work for the summer but suggested I call when I returned to New York at the end of the school year in June.

I did just that, and came for an interview, bringing a sample of my writing as he’d asked me to. I knew I wasn’t enough of a mathematician to do any programming so I suggested that I might do some editing for him. Since he had just produced a lot of remedial courses for some school district in which the black children had not been to school in many years, there was a lot of testing and rewriting for me to do. Initially, I earned 12¢ for each “frame” or index card on which I wrote a question and its answer. This was in the period in which I’d learn how to program: My first assignment was to write a course to teach set theory to young children. What Francis didn’t know was that I didn’t know any set theory! So Jordan taught me set theory so I could do the assignment. When I brought the 600-frame-long program to Francis for review and a critique, he barely looked at it and instead taught me how to play the strategic game “go.” Fortunately, once I began work as an editor, I was paid by the hour ($2.00) instead of by the frame. Even though we were soon spending almost all our non-working time together, I was very careful only to bill him for working hours. Otherwise, even at $2.00/hour, I could have retired long ago!

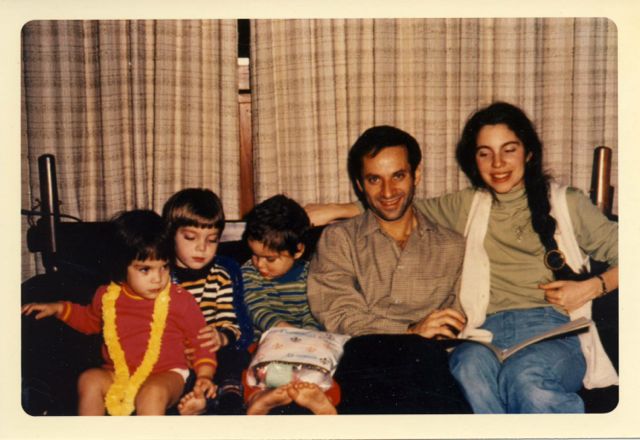

While I am basically a very honest person, I did not tell my parents at first that I was living with Francis. They thought that I was staying in the apartment that Basic Systems had rented for its extra typists that summer. It was only at the end of the summer, when it was time for me to go back to school and that apartment would no longer be used by Basic Systems, and I would have to deceive my parents more actively by concocting another false address, that I told them (on Yom Kippur! appropriately enough) that we were living together. My mother was terribly upset. I’m sure my father was also, but not to the sane extent. They were very unhappy until December, when we married on very short notice. (We were in Brooklyn celebrating Nancy’s third birthday, and we very casually invited everyone to join us at our wedding the following Sunday. Adolph was so excited by the news that when he took us to his office to take our blood samples for the Wasserman test, he forgot to put the plunger into the syringe, and Francis’s blood got all over the floor.) My parents arranged for us to be married in the study of the young rabbi with whom I’d studied while in high school, and we had a very nice small wedding.

I spent that fall semester commuting to Swarthmore. Since I was in the honors program, I had only two seminars a week, one on Monday, one on Tuesday. So, I would spend two days in Swarthmore and the rest of the time in New York, using the library at Columbia and writing some programmed instruction courses on antibiotics for detailmen.

But I had, over the summer, learned more psychology from Francis (even in the first two weeks) than I had learned in two years at Swarthmore. Operant psychology was far more powerful in terms of explaining behavior than was gestalt psychology. And the whole atmosphere at Swarthmore now appeared shallow to me, academic instead of practical, aloof from the world (as critic or reviewer) instead of active in it. I finished out the semester but did not go back in the spring.

I continued to work at Basic Systems, participating in two huge deliveries of materials. One at least was to Pfizer. I remember delivering the camera-ready copy to them after having stayed up all night cutting and pasting illustrations and corrections.

Then in May of ’62 we went on a belated honeymoon to Europe. It was cold in Paris and I was alone much of the tine, since Francis had an average of two business meetings a day. Whether Francis was disoriented because of the amphetamines he’d taken in order to complete the Pfizer delivery before we left, or whether it was a severe case of jet lag, I don’t know. But he wasn’t himself for a few days. My French wasn’t adequate for me to feel comfortable with it. I’d taken French one summer at NYU (free, since I worked for NYU) and then had taken two more courses, but I was better at reading than at speaking. So, the evenings’ activities were the center of the day for me, and that was sometimes a concert or theater, sometimes visiting relatives, but always meant food. We each gained six pounds in three weeks. Our week in Nice was a wonderfully warm, relaxed time. No business meetings, lots of exercise (and food) and so much time together that we soon returned to New York.

Back in New York, I was, for the first time in my life, a lady of leisure. No work, no school, very little structure. If I had that leisure now, perhaps I’d know what to do with it. But then, I didn’t. I played house. I cooked. I took up painting for a bit. I even enrolled in some courses at Columbia. The first semester out of Swarthmore, I’d tried an undergraduate course with Bill Cummings. I found the atmosphere so stifling that I soon dropped it. There was no give-and-take; Cummings’ word was law. There was no discovery; only learning the right facts.

The fall ’62 semester, I tried two courses in the Graduate Faculties — one on South American politics, though I can’t remember what interested me in that, the other a life drawing course.

That was interrupted by the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of that year. I remember very clearly listening to Kennedy’s speech on radio that Monday night. Afterwards, Francis said it sounded like time to leave the country. Who was I to argue? Francis had at least been through that once. I’d rather leave unnecessarily than not leave when I should! So, we spent all Tuesday scurrying around, selling all Francis’s publicly traded stocks, making airline reservations, packing. We’d decided to go to Bogota, but had to fly first to Caracas. One deciding factor in our going there was that in the case of nuclear catastrophe, the southern hemisphere would be somewhat less contaminated than the northern hemisphere. Another was that the Royal Bank of Canada Trust had branches in both cities as well as in New York, and we hurriedly opened an account. I remember getting cash in the 113th Street branch of the Chemical Bank, where I ordinarily got $400 at a time. This time it was $900 or even more. I felt very conspicuous, as if people could see through my pockets and know how much money I was carrying on me! For compactness, I got it all in $100’s, the first time I’d ever seen any in my life!

It was very strange, deciding what to pack and what not to pack. If we wound up spending the rest of our lives out of the U.S., perhaps we should take heavy coats and blankets, the things that would be the hardest and most costly to replace. I don’t remember what I actually packed. Whatever it was, it was less memorable than the decision-making process.

Of course, Caracas turned out to be a much more dangerous place to be than New York was. It was under martial law at the time because of the terrorist explosions set in oil fields and American-owned resorts. Machine gun-toting soldiers were everywhere, and the speed limit was 30 miles an hour.

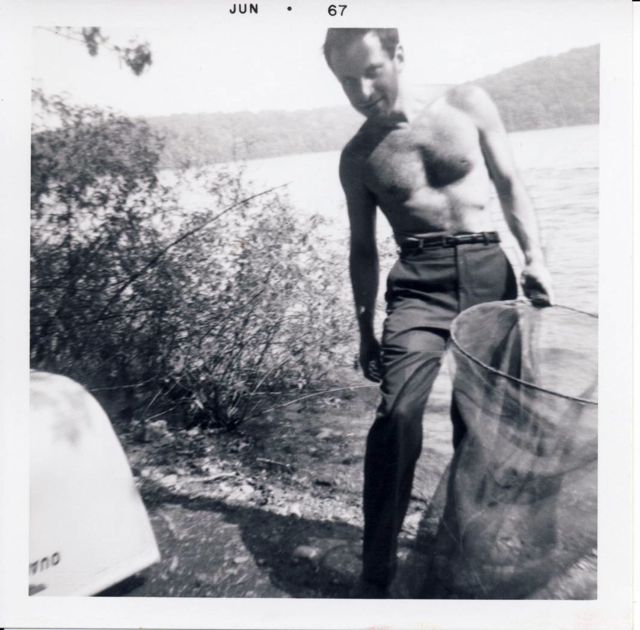

With only two contacts in Caracas, Francis nevertheless managed to spend the next two weeks proposing contracts to various Venezuelan corporations and government agencies. Except for the time I spent typing his proposals on a borrowed typewriter, I was more or less as helpless, useless, and unhappy as I had been in Paris the spring before. How much was the stress of being in a foreign place, how much the stress of not speaking Spanish fluently, I don’t know. I could read all right, but in conversation, I was nowhere. By the time I’d composed and mentally corrected what I wanted to say, everyone else was talking about something else. But we ate very well. And I learned one thing that would change our travelling habits: Once while meeting Francis outside a government building in downtown Caracas after a presentation, we were walking along when Francis suddenly froze, pointed, and shouted “Look!” I looked, but all I could see was the hood ornament of a very old, very black American car. It was some butterfly that Francis hadn’t seen since Havana, and then perhaps only in picture books. Before then, I knew nothing about his butterfly-hunting childhood. This new knowledge was what led me to pack a net in his suitcase when he went to Thailand in ’65. After that, it was easy to get him to take time off to travel, so long as it was to a tropical country.

Once the crisis passed, we returned to New York, and I continued to paint, but without much satisfaction. I would never be as good as Cezanne or van Gogh, so why bother? My standards were much higher than my technique, and I didn’t have the patience to practice, practice, practice. I finally painted one picture that I really liked — an abstract one that now hangs in the back bedroom, and stopped.

I also played the piano a bit. After ten years of lessons and with lots of free time, I might have improved my playing a bit, but there too, it was far easier and more pleasant to the ear to listen to Francis play than to listen to my own practicing.

I wrote up some old studies that Francis had done at Schering but never published, and got them published. I think that was Francis’s idea. He saw how irritable and unhappy I was with no long-term projects of my own, and encouraged me to do something constructive. We still get requests for reprints occasionally, and when I look at the articles, I find it hard to believe that I had anything to do with them. I don’t remember the details and I don’t remember the actual writing, though I know I did it. I have the same reaction when I read old school papers of mine. It’s as if writing is a separate activity from thinking, totally disconnected.

At this time, Francis and I ate out quite a bit, often at the Green Tree or the Gold Rail, a bar where many chess players hung out. It is there that I first met Stuart Margulies and many other chess players I had only heard about. I played a lot of chess then, and the handicap that Francis had to give me in order to break even in our games gradually became smaller. But I didn’t like playing chess too much. I got so competitive and so adrenalized that I had difficulty sleeping some times, and had chess nightmares. One thing the Gold Fail helped me do was lose twenty pounds over the course of nine months. I had always been a terrible eater as a child, very skinny because eating was so aversive to me. It was only when I went away to summer camp when I was twelve and thirteen, and was out of the supervision of my mother, that I began to enjoy food for itself. So I gradually gained weight, about four pounds a year. It was very nice; I wasn’t “Skinny G’dinkis” any more. But I kept on gaining weight, four pounds a year, until I heard with unbelieving ears one September at my school physical, that I was four pounds overweight. Who, me? I didn’t believe it and kept right on eating. When I gained six pounds in three weeks in France in ’62, I realized that I couldn’t go on that way. I weighed 136 pounds! So Francis and I made the single change in our diet of sharing the steak, salad and baked potato at the Gold Rail instead of each getting one. That was the only thing we did, aside from noticing when we were no longer hungry. I don’t know about Francis, but when I weighed myself again nine months later, I was. down to 116, and I’ve stayed there (except for pregnancies) ever since.

In July ’63, Francis and I moved to 380 Riverside Drive, one flight above Don and Dawn Cook’s apartment. It was enormous — five whole rooms, light and airy, with oddly-shaped rooms and balconies at the windows. And two bathrooms! We had to buy a lot of furniture; we had already gotten a lot from our parents — teak bookcases from the Mechners, a dining set from the Weitzbergs, and some lovely ’30’s light oak desk on loan from Joan when she and Marty broke up. I liked that light oak so much that all our window trim in our house now is light oak. I enjoyed designing and building bookshelves and other something-from-nothing projects. And I started to sew: curtains and clothes. I enjoyed doing things without a pattern to work from. Many projects were left half-finished when I couldn’t work my way past some obstacle or other. But I still enjoyed the challenge of the problem-solving process enough to keep on doing it that way, even if the results were sometimes unsatisfactory. The victories were few but very satisfying.

It was some time after returning from Sao Paulo in the summer of ’63 that I started working on the programmed instruction course to teach Francis’s notation system. It was the biggest project I had done on my own, and involved contacting psychologists and asking them to test out the first version in their classes. What I remember best (or is it worst?) of the whole project was taking the enormous parcels of copies to the General Post Office one Saturday to mail them to the various psychology departments. It was raining. And I was somewhere in my second month of pregnancy with Jordan and very easily fatigued. It turned out that one or two of the heaviest parcels were oversize — and the post office wouldn’t accept them for mailing. I couldn’t just take a cab home, because we were having a huge party that night, and I had to buy food and serving pieces at Altman’s before going uptown. So, there I was, lugging these heavy parcels in the middle of Eighth Avenue, trying to get a cab cross town three blocks, and no one wanted to take me on such a short ride. I don’t remember what finally happened, but that whole scene comes back to me still, on occasions when I feel totally overwhelmed and unable to cope.

My children might find it hard to believe, in these days when they do so much of the cooking and I do so little, but I did once really enjoy cooking and creating recipes. Francis enjoys creating recipes too, but only those that don’t involve heating any food. He combines ingredients in novel ways. But he doesn’t cook in the usual sense of the word. So how did he teach me to make Wiener Schnitzl and potato salad?

In case he didn’t tell you, Francis’s very favorite meal, as a child, was schnitzl and potato salad. He used to phone his grandmother to see what she was going to make for dinner. Then he could decide, on the basis of who was making schnitzl, where he would eat that night. He kept promising me, from the time we first met, that he would teach me to make it for him. I kept waiting for the lessons to begin, and when they didn’t I started out on my own. Each time I made it, Francis would tell me either “Yes, it’s more this way,” or “No, last time was more like it.” In this way, he shaped my behavior until I make both potato salad and schnitzl just the way he likes than.

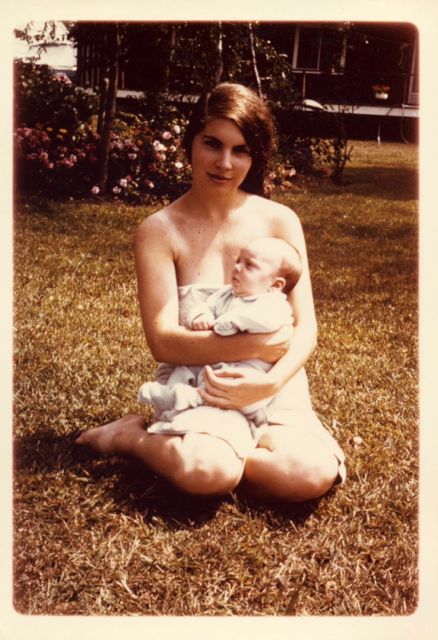

The biggest change in my life started when Jordan was born. I was not used to having anyone completely dependent on me. It was very scary and wonderful at the same time. Jordan was the second young baby I’d ever seen close up, and the very first I’d ever touched. I had never babysat as a teenager and knew what little I knew from books only. (In fact, the day Kennedy was assassinated, I heard the news of his shooting as I entered the elevator outside the psychology department’s library where I’d been boning up on child development.) He had a jaundice problem as an infant, which was only later traced to some hormone in my milk that prevented the bilirubin from combining with whatever-it-is that it has to combine with before leaving the body. The hormone combined with the whatever-it-is, instead, leaving none for the bilirubin to combine with. So, it just kept building up.

I had made a poor choice of pediatrician from the standpoint of human relationships. He may have been very bright and a good diagnostician, but he was very callous. When I wanted to continue keeping up my milk supply until all danger of jaundice had passed (Jordan was already 6 weeks old by this time), he told me outright, “You’re crazy.” What was a first-time, easily intimidated mother to do: argue with him? It was only after Linda had also begun to turn yellow when my milk came in, and turned pink as soon as I stopped, that I thought out a plan by which to get around the problem: I’d nurse her only once in a while, until all her excess red blood cells had been excreted and her immature liver had matured a bit. Then I’d gradually increase the frequency of nursing. A wonderful idea — it later worked perfectly with Emily and again with David — but Linda was so used to the bottle by the time I’d thought of it that she rejected the breast and I didn’t want to force “poison” on the kid, so I let it pass.

It was a great victory when I finally began nursing Emily full time at age three months. I’d started once a day, then twice a day, always stopping short of having her turn yellow. I then nursed her very happily till her second birthday. With David, I was bolder and nursed him full time from the time he was only a few weeks old.

What amazed me and still amazes me is how different each of the children is and was from the very moment of their birth. I, who used to believe that behavior was totally learned, began to see innate character traits, from day one. Jordan was persistent in everything. He would struggle (with much terrifying noise) until he could wriggle so his head would be tightly stuck into the corner of his crib or carriage (or dresser drawer that first night home). Then he’d quiet down and fall asleep. And when he was pulling himself upright by holding onto his folding gate at the door of his room, he’d scream until he got up, then he’d scream (because he couldn’t sit down) until he fell down. Then he’d get up again without pause. And when he started drawing or playing the drums or writing or anything, it would be with total concentration.

Linda was very cuddly and physical, again from birth. She came out and within five minutes was sucking her thumb. She held on very tightly to me, like a little koala bear. When she was a week old, I noticed her follow the motion of my mother’s walking past her crib. I figured if she liked watching things move, I’d give her something to watch. I hung a wooden rattle in her air crib so that it reached to within one inch of the mattress. She quickly learned to hit it with either her fist or her foot. Then she’d watch it swing until it stopped moving and hit or kick it again to set it going. Where Jordan was very cautious, Linda was very adventurous. He took one step. A few days later two steps. Always under perfect control. Linda practically ran before she walked and didn’t mind falls, the few she had. Perhaps her more generous padding had something to do with it?

Jordan learned to climb down stairs backwards, reaching behind him with his toes extended. Linda learned to climb downstairs head first, reaching ahead of her with her arm extended. She scared me one day by going headfirst off the low black leather chair she was sitting on the living room. She couldn’t have been more than eighteen months old at the very most when she did that. I was scared, but she enjoyed it and knew just what she was doing. Later, she’d teach herself to dive and to do somersaults in the air into beanbags. She reminds me at times of Francis jumping from sharp rock to sharp rock out through the surf in San Juan, while I watched with my heart in my mouth.

Emily was still different. Whereas Jordan and Linda would follow me around the house wherever I went, Emily would go off on her own where no one would disturb her, even when she had to creep and crawl to get there. She spoke in very long and very sentences from well under the age of two.

And she always wanted to understand everything. I remember being startled one morning when she came to my bed and asked me, “Why do you sleep like that Mommy with the underpants on your head and your hair sticking out?” (I sometimes wore a pair of Linda’s cotton underpants to keep my long hair up at night, since my hair was heavy and no hairnet would hold it in place.) She was also very reluctant to join into any activity in which she wasn’t proficient. This showed up a lot when she was five and went to summer day camp. She would watch while the others played and would resist all attempts on the part of the counselor to entice her to play, until she was good and ready. The counselor was so struck by it that she told me. And even before that, the staff at the Discovery Center in White Plains had told me the same thing.

Jordan and Emily were both extremely hard to distract from what they were doing. Heads in their books, they were/are oblivious to all going on around them. Linda and David, at the other extreme, were/are very easily distracted. When David was still nursing, he would let go of the breast in order to follow any interesting shenanigans on the part of his siblings (and there were many of those!); no matter how hungry he was, watching people was more important to him.

Anyway, I hope they all add their stories to this family history before much longer. They can tell their own stories far better than I can.

We started looking for a house when Jordan was a year old. With the Xerox money, we could buy either a townhouse in the city or a country house. I was pregnant while we were in Europe and Israel those three weeks in May and June, but I miscarried (at six months) in July, so the pressure to find a new place was off for a while. Francis was wonderful. His first comment when we realized what was happening was, “Don’t worry; we can have another one.” Something that might have appeared to be a tragedy was then just what was happening, nothing more. The only really bad part of it took place in the car as Dr. Klotchkoff drove me from the apartment to the hospital. He didn’t answer right away when I asked him why he was taking me to the New York Infirmary instead of to St. Vincent’s. In that split-second pause, I suddenly realized that my life might be in danger, and that he didn’t want me to be in a hospital where they would try harder to save the baby than to save me. I had never thought there might be risk to me in this babymaking business. Fortunately, all my other pregnancies went very well, and we continue to be blessed with good health, something we have our parents and their parents to thank for.

The one sacrifice I made in having young children was giving up things requiring concentration or physical care. I stopped knitting when Jordan continued pulling the needles out of my work. I put breakables out of reach. I stopped wearing clothes that stained or spotted easily. But the worst part was not being able to carry on conversations without interruption. It took me several months of practice once all the kids were past toddlerhood before I could have a non-trivial discussion. The problem was that I became so used to interruptions by the children that I’d interrupt myself if they didn’t do it.

One interesting break in the routines of childrearing came when we were still in Usonia, in the long interval between Emily and David. Francis and Ron Richards thought that what the Discovery Centers needed was a showcase computer set-up where kids could play games at a computer terminal. In those days there were teletype terminals, not the CRTs so prevalent today. Ron thought that I’d be ideal to do the programming and game design. I was flattered but skeptical. But he taught me enough about Fortran in a few hours that I felt confident I could do it. He put me in touch with a computer programming expert who suggested I use another language — Snobol 3 (now extinct) — to program the games. I had such fun! I worked mostly at night when the kids were asleep and the time-sharing and phone rates were lowest. I even got paid to do what was the most fun I’d ever had! I had total control over the project, designing games I thought would involve more of the child’s creativity than most computer games did at that time.

There were no computer graphics available, since we were limited to the ordinary keyboard symbols. I made a hangman game and a program that would print out in banner form whatever the child would key in. The best — as far as I was concerned — were the stories. I wrote a story-writer program, a general set of instructions for substituting kids’ answers to the computer’s questions to fill in the blanks in the stories I wrote. The story that would be printed out at the end would include the child’s answers to a whole series of questions. It would be about his/her pet, family, balloon, trip to the zoo, or whatever. Jordan used to play those games by the hour, putting in false answers to the questions and howling with glee when the computer then printed out crazy, nonsensical stories.

The only frustration was that the games were never fully implemented at the Discovery Centers. They were really thought of as window dressing, and I guess they were. There was no integration with the other elements of the center program, and I never had a chance to train the center personnel in the use of the games. But I certainly enjoyed the thrill of creating something so interesting, of seeing that I could master something I knew nothing about, and that I could still concentrate on work. My disposition improved tremendously with interest in a long-term project that was bigger than I was.

I was involved somewhat in the Paideia School, finding the site, convincing the somewhat traditional teachers who owned the campus that our style of teaching did not threaten their style or them, taking certain students into the city to work at the CUNY computer center, buying a printing press and type and teaching the kids how to set type and use the press, tutoring in math.

But I didn’t realize how much Paideia meant to me until it had folded. Good as the Chappaqua schools were, there was no framework in which a student could do independent work or take an active voice in decisions concerning his curriculum. In the fall of ’73, shortly after the decision was made to close Paideia, we had a meeting of interested parents at our house, in which we discussed the possibility of a Saturday school or an after-school school to fill the void. Nothing came of it except a conviction that there were people out there who also felt the need for more in the way of training children to take partial responsibility for their own educations.

Later that same year I realized that no one at the Grafflin School (the public school in which Jordan, Linda, and Emily were enrolled) ever called me to do any of the things I’d volunteered for on the form I’d filled out at the start of the school year. I looked into why that was so, and learned that the volunteer forms are kept by the class mother of each class, and that each class mother would look for resource persons to meet requests by “her” teacher only among the forms submitted by the parents of students in that class. Aha! thought I. What’s needed here in order not to waste the wonderful parent resources we’d made such extensive use of at Paideia was a centralized, school-wide resource bank, not a separate small resource bank for each class.

I volunteered my services to the school principal to set up such a resource bank. She graciously accepted and warned me not to expect too much use by the teachers. Directories to parent resources had been done before and usually lay unused in teachers’ desks. Oh, said I, making it up on the spot. This wouldn’t be a directory, but a “loose-leaf” file, constantly updated and available in the library so anyone could go to it or even call the librarian for help in finding the right person.

So, I wrote a four-page questionnaire to be given out the following fall at parents’ night. Hidden in it were a few questions that I thought would help fill the need for independent projects that the Paideia parents still felt the schools did not provide. The way I thought about it was this: It’s not practical to expect children to go to school Saturdays or after school. Private school days don’t last very long. The public schools should provide the opportunities for independent projects. But they won’t agree to do so, even if they thought it was a good idea, because they don’t have the staff to guide students through their projects. They have more than they can handle right now with the ordinary curriculum.

I’d thought of a way around it one day while working as an aide in Linda’s second-grade classroom. Between listening to one student read and correcting the math workbooks of some other students, I noticed Linda looking out the window with great interest. I asked her what was so interesting out there. She said that the snow was falling all over, but it was only sticking in some places and not in others. In particular, there was one path where the snow was (or wasn’t; I don’t remember which at this point) sticking. Why was that? I didn’t know, but I knew what I’d do to help Linda find out, what sorts of experiments she might set up to find out, and how she could think up her own experiments to test various hypotheses. In a flash, I decided that what the school should do was to set up a resource person — not a librarian whose approach to “research” is to look up answers in a book, but someone who would sit, waiting for students with their OWN questions, and then help the students clarify and narrow their questions, think of how to look for the answers (in books or by asking people who knew, or by setting up experiments) and then act as guide or mentor throughout each child’s project.

Clearly the school would jump for such a great idea if there were ready and willing mentors already lined up for them to tap. So that’s one of the questions I put in the volunteer questionnaire: Would you be interested in being a mentor to a child working on an independent project?

Nothing ever came of the mentor idea; it’s still in my head. But a lot cane out of the response to the parent questionnaire. I interviewed about sixty parents and set up a card file of resources in a shoe box. That file was later mounted on a rotary recipe/picture file and sits, even gets used, to this day in the Grafflin School library. Many of the people in the file no longer live in the area.

In interviewing the parents, I realized that there are needs that they can fill for one another, too, not just for school children. There were people in the same business who didn’t know one another. I met a wonderful woman who had just come back from three years in Japan and who wanted to sell some of the antiques she had collected there. We are friends to this day (though she has since moved to Houston and then to Darien) and Joan and I and several other friends bought antiques from her. Lisa has a wooden cake carrier that Joan and I bought for her from this woman.

I also realized that it was foolish to limit the resources to parents. What about older siblings? People who just worked in town but didn’t live here? People without any children? With grown children? And so on. So, I proposed to the Town of New Castle (the town that contains the hamlet of Chappaqua) to set up a town-wide resource bank, to serve all legitimate needs, not only educational ones. They accepted my proposal and gave me a very modest budget to cover telephone, answering device, some supplies, and cheap printing. I started alone and quickly built a staff of five volunteers, each of whom worked one afternoon. (David at that time — September ’75 — was in kindergarten mornings at the Woodland School, so I could only work mornings. We had had no household help since the spring of ’74, not even day help, so I had to work around the children’s school schedules.)

One of the volunteers was a very dynamic woman in her early fifties, divorced, her only child grown, eager to build this project into a major force in the community. It gradually became clear to us, in running ACCESS (as the project was called: A Comprehensive Community Exchange for Skills and Services), that even the town was too small an area in which to operate. People would call and ask for things that we could easily find if we could make some phone calls or look outside the town. And other people listed services that no one ever asked for but that might have a market outside this one town. We decided by March of ’76 to incorporate as a business and go out on our own once our year’s experiment with the town was over.

We couldn’t get the name ACCESS, nor could we get TeleQuest, so we settled for OmniQuest inc (after considering literally hundreds of names). We began to charge for our services, a painful step for people with no background in charging for services. We ran into some resistance to paying for services that many thought should be free (“The librarian doesn’t charge us for information; why should you?”) and gradually turned more and more to the commercial/industrial market rather than the homebody market that had used us in ACCESS.

Now, five-and-a-half years later, OmniQuest is still evolving. I bought out my partner, Dorothy I. Goldman, about two years ago, when she began to spend substantial time at other (paying) temporary jobs and I realized I got more done without her to distract me than the two of us together did.

Much of what I do is marketing research — finding out about the markets for various products. The biggest project I’ve done so far was for GCC (an NTC subsidiary), researching the markets for window shade hardware and for electromechanical/electromagnetic clutches. I’ve also done a preliminary study of industrial markets for pipe cleaners (for U.S. Tobacco, of all companies!) and hope to do a larger follow-up study later this year or early next year.

I still need to be more aggressive in going out and getting new business. I enjoy responding to a need expressed by a prospective client, but I feel uncomfortable making cold calls and asking “What do you need?” So I do things to increase the number of inquiries I get. U.S. Tobacco came to me after I joined the Ad Club of Westchester (when my brochure won an award last spring). And I got a contract with a law firm that represents Porsche Design Produkte of Austria when the wife of one of the attorneys in the firm saw a reprint of an article in which my brochure appeared. I’ve written an article on how to do market studies for In Business, a magazine written primarily with the small-scale entrepreneur in mind. It will be published later in October 1981, and I hope it will bring some business.

Previous articles have rarely brought much business, but I think that is largely because the publication didn’t reach my main market, which seems to be small-to-middle-sized companies. I still remember the kinds of calls I got after an article appeared about OmniQuest in the Village Voice. Boy, were they weird: Could I find opium pipes? Could I generate a list of the hundred most eligible (read “rich”) bachelors in New York? Could I help this fellow gain three hundred pounds? I did and do still find hard-to-find products and information, but only when the purposes are legitimate.

I enjoy designing systems and objects that will solve various problems. Two of my favorite such systems involve Francis’s hobby of butterfly collecting. When I first watched him mount butterflies, he used glassine strips to hold the wings down. That’s standard procedure. I had difficulty seeing through the translucent paper and wondered how he could tell when the wings were positioned exactly symmetrically, so I suggested he use clear film leader. He tried some, loved it, and has been using clear acetate strips ever since.

The second butterfly innovation was in the design of a case for carrying butterfly boards on long trips. The problem there was that the case Francis had built could hold only so many boards, and even with a light-bulb to heat the butterflies to dry them faster, the number of boards was too small to keep up with the rate at which Francis could catch and mount them. My inspiration struck the night Francis was inventorying his butterfly collection. He said something about having more small ones than big ones and I immediately realized that instead of having one standard-size spreading board for all butterflies, we should have smaller boards for the small butterflies, middle- sized ones for the middle-sized ones, and so on. That way there would be far less wasted space. So, Francis figured the ratios of each size butterfly in his collection and gave me the specifications for the boards. Once he knew he could design his own, he made great improvements on the standard design. He specified tapered surfaces instead of flat ones, very narrow grooves for the smallest butterflies, and much thinner boards for decreased weight. Of course, the main saving was in the decreased width of the boards. I designed a system for attaching and detaching the boards from an aluminum suitcase, using velcro strips and a two-sided center board. Francis now has enough board space within that one case to allow ample time for the first-mounted butterflies to dry naturally and be removed for storage, before the last board is filled.

Imagine my horror when I saw Francis ask the kids to throw the beautiful, shiny case down our stone steps and to hammer on it! He then wrote his name on the outside of the case in indelible magic market so no one would want to steal his treasure. Once again, function dictates form.

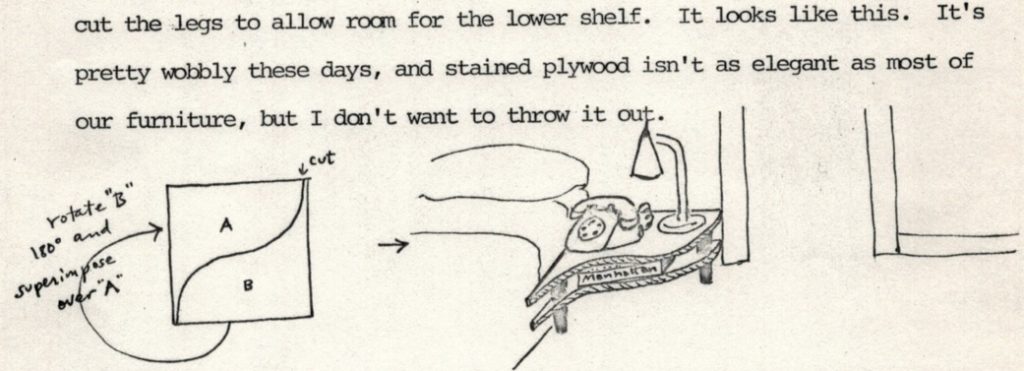

I enjoy designing furniture to meet special needs. My first project was a night table for our apartment at 435 Riverside Drive. It had to hold a lamp and a telephone and a telephone book, and it had to not stick out and catch people’s shins in the small space between the bed and the door. I designed it to be cut out of one small piece of plywood, and cut the legs to allow room for the lower shelf. It looks like this. It’s pretty wobbly these days, and stained plywood isn’t as elegant as most of our furniture, but I don’t want to throw it out.

I had a small storage and cutting cart made for Lisa’s tiny kitchen once, and designed some magazine racks for our house in Chappaqua, as well as a telephone table. I left the grander design to Francis — a whole house being more than I can handle — and took on small, manageable problems!

The system I’m proudest of, though, is the chore system that has evolved over the last two years, as a way of getting the children to participate more in the running of the house. We have a marvelous cleaning woman — Juana Lago-Pineiro — once a week. (Juana was perhaps the best “find” of that whole year with ACCESS; an English-speaking friend of hers brought her into the ACCESS office in downtown Chappaqua one afternoon to find some work for her. Juana had been in Spain for four months visiting her mother and her son, and now that she was back she wanted houses to clean. I immediately fell in love with her warmth and sense of humor, apparent even though she barely speaks any English, to this day. The timing was perfect: It was right before Passover, and we were going to have a houseful of people, and the house hadn’t had more than a lick and a promise (cleaningwise) from me in two years! The house shaped up very quickly. Once a week might keep the house clean, but it doesn’t keep it tidy. There had to be some way to specify the chores that needed doing between times, and some way to apportion the chores fairly among the children and me. Francis was largely exempted from this system, not only because his schedule is so unpredictable, but also because he’s busy all week working to support us. He does take out the compost when he’s home, and he’s wonderful about tidying up before we have guests.

I don’t want to go into all the details about the chore system, but it did involve everyone — assigning values to each chore according to its difficulty, how long it took, or how unpleasant it was to each person. In this way, taking out the garbage once a week, a five-minute job, was initially rated as five times “worse” than washing the dishes after a single dinner. We then averaged the five ratings for each chore and calculated how many “points” we each needed to do for our share of the week’s work. We took turns choosing our chores for the week, carefully altering the sequence in which we got to pick so that none of the children would have an advantage over the others. It took more than an hour the first time we picked chores, what with all the complaints and side comments, but after a while we settled into more-or-less fixed jobs according to ability, preference, and regularity of being at home for dinner.

Linda wound up doing the cooking, Emily did most of the laundry on weekends, Jordan did most of the after-dinner dish-washing, and David mostly by default wound up setting the table and clearing it afterwards. The definition of each chore changed from time to time. We became much more flexible during the summer months, having people do what was needed when it was needed, without signing up ahead of time. The biggest change came when Jordan went off to Yale at the end of August ’81. Now I do all the dishwashing, Linda and I each cook three times a week, David and Emily alternating weeks for the seventh cooking slot, I do all the laundry, with some help from Emily, David does all the table setting, Emily clears and David does the counters or they switch. I do more of the chores than I’ve done for the last two years, but I don’t mind because the kids have a more cooperative attitude about doing some of the work too. We do make a good team. And the children have learned valuable skills.

The inspiration for the chore system was the Sucher family. We had visited them for Thanksgiving a year or two before, and I was impressed with what happened after meals. Joe would get up, clear the table, and shoo all the women out of the kitchen. When I offered to help, he’d refuse, saying the women had done enough work before the meal. He and the boys would clean up. What amazed me even more was that Francis volunteered to help him, and for the duration of our visit, helped Joe clear up after every meal. I was disappointed when on our return home, Francis reverted to his pre-visit disappearance immediately after each meal. I realized then that it had to do with expectations, and clearly I had set up everyone’s expectations that I do all the kitchen and household work. It took me several months to realize that I wanted to change those expectations, for the children even more than for Francis, and another few months of mulling it over before I figured out how to go about it.

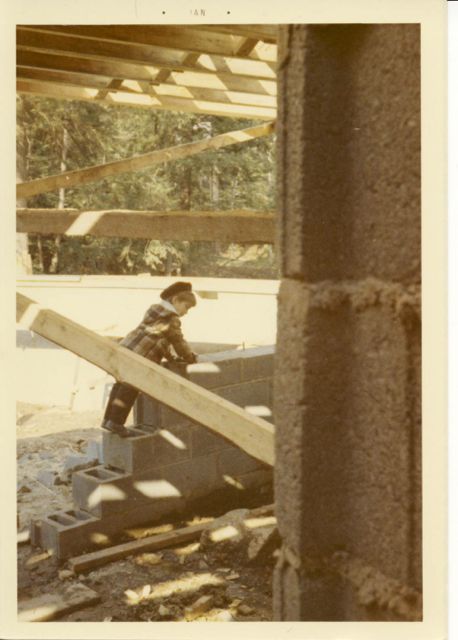

When Francis and I designed the house back in ’69, we had three very young children. David was born the day after we moved into the house. It wasn’t finished and we didn’t get our certificate of occupancy for another seven months after that. I used to meet the building inspector with David in my arms each time the inspector came to tell us we shouldn’t be in the house. We had workmen in the house every morning for all that time. There was a ramp leading up to our main door, where there are now stairs. Between the top of the ramp and the doorstep was a chasm with a narrower ramp across it. I held my breath each tine the children went in or out. Our frisk English sheepdog, Livvy, used to race them and head them off. We finally gave her away because she wandered and because we were afraid she would “shepherd” some guest off the precipice! Bingo, our basenji, was killed by a neighbor’s car in April ’71. He had survived an earlier accident just before our move from Usonia to Chappaqua, and Jordan, 6 1/2 at the time, attributed his second accident to the earlier survival: “He thought he was immortal.”

Bingo’s death left us petless, but not for long. A neighbor’s kitten kept following Linda home, and we asked them if we could adopt “Martin.” Linda received him as a gift for her fifth birthday and promptly renamed him “Stripes.” Stella Forster gave two kittens to Jordan and Linda the following year. Linda still has “O’Malley,” but Jordan’s grey and white “Snoopy” was killed by a neighbor’s Great Dane while still a kitten. Jordan then swore off pets.

David and Emily each got a kitten from a friend of David’s. Emily’s red and white “Huckle” has recently disappeared. But David’s “Bullet” still comes around for food. Since Francis is allergic to cat dander, we try to keep the cats out of the house as much as possible. O’Malley climbs into Linda’s room through her ground floor window — the same window that her dog Simba uses for going in and out. But David’s room is on the top floor, so he cannot bring Bullet in quite so easily.

Linda’s love for animals has been quite strong for as long as I can remember. She has wanted a horse since the time she started riding lessons with the daughter of Dave Whitney, an employee of Francis’s at UEC. Was she five or six? I don’t remember exactly. Her lessons stopped when the horse jumped a fence unexpectedly and threw Linda on her head. She wanted to continue, but Francis and I felt a bit guilty for having allowed her to do something so inherently dangerous. She has ridden off and on, mostly off, for the past few years, and will start again as soon as she finds a suitable stable close enough to our house. She would get a horse to keep on our property if we let her, but neither Francis nor I want to embark on such an expensive, time-consuming, venture. Linda will have to wait.

She plans to become a veterinarian and shows signs of becoming a good one. She has a way with animals of all kinds. At one time, before she got Simba, she had about forty small animals in her room: mice, guinea pigs, hamsters, parakeets, gerbils. She would exchange the babies for food at the nearby pet shop.

The only pet that I myself had since my childhood was a 7-year-old Nubian goat, “Nancy.” She was supposed to have been pregnant when we got her, but it proved to be a false pregnancy, and subsequent attempts to impregnate her also failed. Not only didn’t we get any milk from Nancy, but she ate anything she could reach. Once she nearly killed herself by eating a lot of mountain laurel. She reeled around as if drunk and vomited up enough so that she quickly recovered. What really bothered me was that she would eat the native plants I was trying to establish close to the house in a sort of wildflower garden. She loved ferns and daylilies, and could munch them down to the ground faster than I could transplant them or they could grow. So, we gave her away to a family in Dutchess County who had other goats and lots of room.

We had plenty of room for a garden while in Usonia, but I was pregnant almost constantly and was very lethargic. I rarely walked down into the patio, let alone down to the yard. We did have a small garden our first season in Chappaqua, but the raccoons and rabbits harvested more of it than we did so we abandoned garden plans. Instead, we forage for wild berries and mushrooms. Imagine my not knowing that there were morels on the Usonia property! I might not have moved away had I known…

Until the surrounding houses were built a few years ago, we used to get wonderful wild strawberries, blackberries, a few blueberries, fox grapes, and the most perfect, 16-inch diameter grape leaves you could imagine. I would harvest the leaves by the bucketful and blanch them for use in stuffed vine leaves. Now that there are houses all around, we content ourselves with the wine berries that I planted in our septic field from by strewing the fermented “raspberries” that Fred Kantor had brought from his parents’ house in Silver Spring, Maryland, many years ago.

Perhaps in the refurbishing of our house, that Francis and I are about to begin, we will clear some area for planting berries and other crops that will fit in with the natural terrain.

Our main “garden” is the area around our swimming pool. I never had much of a green thumb. We were always fortunate to live in apartments or houses where we didn’t need to cover our windows for privacy, so plants did pretty well on their own. When we moved to Chappaqua, I put the plants that Hedy gave us into the pool area, so I wouldn’t have to take care of them. I had my hands full with fixing up the house and running the household and taking care of the children. Even with two college girls to help me, there was always plenty to do. And basically, I had no interest in plants. But the environment in the pool area was so perfect for plants, very humid and not too warm, that they began to grow so well that even I took notice of them. I cut back the “wandering Jew” and coleus that Mother gave me, and rooted the cuttings. Soon, I had so many plants that I couldn’t hack them back fast enough and I had to give the cuttings away as they kept spreading towards the pool and covering the path around it.

Francis gave me a gift of some plants, which we picked out together, and then my interest really grew. Ferns especially grew well. I began to take courses at the Kitchawan Research Laboratory of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, here in Ossining. And I went on nature walks led by local naturalists.

But the main impetus to my gardening was a butterfly trip I took with Francis to Brazil in ’73. We hadn’t gone on one in a long time. When I was pregnant with David, I was supposed to meet Francis in the jungle in Peru, but Linda’s sudden bronchitis prevented that. Then, when I was nursing David, I didn’t want to risk taking him into the jungle, so I sent Francis on two trips with Adolph instead of me. Imagine my surprise when, on this trip to Brazil, I couldn’t keep my eyes on the butterflies! All I could see were the incredible plants I’d never noticed before, the ferns more than any others. Some were six to nine feet tall. And the curled-up croziers, the new leaves about to unfurl, were sometimes bright purple.

I could scarcely control myself. I smuggled some plants into the country, carefully removing all soil from their roots and wrapping them in damp newspaper. The first thing I did upon my return — after transplanting the specimens, of course — was to apply for an importing permit so I could bring in plants legally. I was proud that the survival rate for plants I brought in was higher (about 60%) than that of the curator of ferns for the New York Botanical Garden. I first met Dr. John Mickel when I was trying to identify one fern I’d collected on that first trip, and the visiting expert at Kitchawan, Gordon Foster, couldn’t identify it. He told me to ask Dr. Mickel, who invited me to a meeting of the Fern Society. I went and was so enchanted with what I learned about ferns that I became a member and went regularly to their meetings for a couple of years, until my business took up most of my time and energies.

When the Botanical Garden emptied its conservatory in order to rebuild it, we worked one day to dig up their fern collection so it could be moved to the propagation houses for the duration of the construction. As a reward, those of us with greenhouses got to take plants home with us. It was not only a reward, of course; the idea was to disperse the collection to several places in case the specimens in the prop houses suffered too much through the winters. Dr. Mickel warned me to spray the plants thoroughly before bringing them into my greenhouse. But I was so fatigued by the day’s work and so eager to get them transplanted, that I only hosed them down. As a result, I introduced several varieties of scale, mealy bug, and spider mite into the greenhouse. Most of the ferns survived, but some of my other plants died as a result. The beautiful banana plant that Father gave Francis for one of his birthdays finally succumbed to a combination of mites and bitter cold. Once we install radiant heating panels in the pool area, we should be able to provide the plants with enough warmth that we can keep them healthy without bankrupting ourselves. (Our house is all electric, and the Con Edison rates have more than tripled since we’ve been in the house, even though we’ve cut back our usage to less than half of what we used to use.)

Adolph and I took the est training at the same time in May 1978. He took it largely at the urging of Nancy and Joan and Marv. I took it largely out of curiosity based on the experience of Susan Tanen, who took it because of Joan and Marv. It was a very moving, constructive experience for me. Francis immediately noticed that I was less defensive than I had been. Jordan took it right after I did, and Emily and David signed up on the waiting list for a children’s training. Over the next two years, my whole family took it, even my mother! who had once said she never would. We all got a lot out of it, each in our own way. Jordan repeated the training and Emily took the standard training when she was old enough to, after having done the children’s training. I have still not given up altogether on my hopes for Hedy’s doing the training. I know it took her a long time to get me interested in plants, so I’ll be just as patient and just as persistent. If Adolph could get rid of his migraine headaches and terrible skin rash within a month of completing the training, and everyone else finds at least some value in it, I’m sure that she can also.